Despite the low occurrence, the challenge to the surgeon is considerable and requires a well-planned and coordinated approach to maximize the outcome. The primary factor that creates the technical challenge is the relative inaccessibility of the reproductive tract by routine celiotomy techniques. The mesovarium and the mesometrium support the ovary and the uterus in the dorsal-most aspect of the abdomen. This feature of the mare’s anatomy dictates that open surgical approaches require maximal tension to achieve minimal exposure of the tissues, which increases complications to the mare and limits the surgeon’s ability to function effectively. Added to the poor exposure is the compounded risk of abdominal contamination from a diseased uterus. Laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy techniques minimize the primary challenges by allowing excellent viewing, tension-free dissection, and hemostasis of the suspensory structures and vessels of the ovaries and the uterus. Despite the limited total number of mares operated that is reported, there are a variety of laparoscopic-assisted methods described. They include both partial and complete ovariohysterectomy in the standing and recumbent mare, both with and without hand assistance (Broome et al. 1992; Delling et al. 2004; Janicek et al. 2004; Rötting et al. 2004; Ragle 2005; Muurlink et al. 2008; Gablehouse et al. 2009; Heijltjes et al. 2009). There is significant merit to combining the advantages of standing laparoscopy—for example, better viewing and access with the naturally suspended ovary and uterus—with the advantages of a ventral midline celiotomy—for example, linea alba providing good hemostasis and secure closure and the ability to extend the incision to the edge of the pelvis so that resection and closure of the uterus can occur outside the abdomen to reduce intra-abdominal contamination (Scharner et al. 2009). At present, one limitation of laparoscopic instrumentation is the working length of the common vessel-sealing instrumentation, which fails to reach to the caudal mesometrium in larger mares during standing laparoscopy. It is more than adequate to free up the majority of the ovaries and the uterus to be pulled through a midline celiotomy where the rest of the dissection can continue. The surgical description below will focus on the entire procedure being on the dorsally recumbent mare under general anesthesia.

Anesthesia, Positioning, and Surgical Preparation

Normal preoperative screening prior to surgery is standard. Horses that present with no significant current or past illness receive a physical exam, including a rebreathing exam and an electrocardiogram. Complete blood count (CBC) with packed cell volume (PCV), total protein (TP), and serum chemistry is performed.

A major presurgical effort is focused on reducing the uterine lumen contamination and the size of the uterus prior to surgery. A reproductive specialist should be part of the surgeon’s professional team to aid with selection of candidates for ovariohysterectomy and in helping prepare the uterus for surgery. Results of uterine culture and cytology with antibiotic sensitivities should be obtained prior to the operation. In a few cases of pyometra with a damaged cervix where it is considered too difficult to establish drainage and lavage standing before recumbent surgery, drainage is performed under the same general anesthesia as the operation (Boussauw et al. 1998).

It is also important to reduce the intestinal contents prior to surgery to improve intraoperative viewing. The preoperative diet is modified by feed withdrawal or feeding a high energy, low bulk diet. Water is not restricted prior to surgery. A 450-kg horse will have a digestive tract volume capacity of about 200 L of ingesta (Kararli 1995). The weight of the gastrointestinal contents will range from 5% to 10% of the body weight depending on the diet composition (5% with concentrate and 10% with roughage) (Harris et al. 2006). Intestinal transit time, or mean retention time, of feedstuffs in horses varies in studies from 18 to 60 hours depending on the methodology of measurement, diet, level of exercise, and so on (Van Weyenberg et al. 2006). For clinical application, it is considered that 45–72 hours are required for food to completely pass through the digestive tract of the horse (Swinker 2002). The goal is that prior to surgery, the horse should be concave in the paralumbar fossae. Observing the concave shape in the flanks and a low intestinal bulk detected during transrectal exam are the best indicators that the operation can proceed. Depending on the horse, the time to achieve this can vary from 12 to 72 hours. The alternative to complete feed withdrawal is to restrict feed to a low bulk, high energy diet (e.g., 1 cup of soaked complete pelleted feed with 1/4 cup corn oil four times a day) until there is a concaved contour to the paralumbar fossae (∼48 hours).

The greater the internal body fat, the more important it is to reduce the contents in the gastrointestinal tract. Excess internal body fat has a significant negative impact on the size of the laparoscopic visual field and in the ease of establishing and maneuvering laparoscopic portals. Although the body condition score may be one indicator of possible excess internal body fat, some horses seem to have greater internal body fat (especially in the retroperitoneal area of the ventral midline, falciform ligament, paralumbar fossae, mesocolon, and mesovarium) than their amount of subcutaneous fat would suggest. Transrectal examination is performed prior to surgery to evacuate the rectum and to confirm the reproductive tract status.

Before laparoscopy, the horse is administered penicillin G potassium (22,000 U/kg [10,000 U/lb], IV), gentamicin sulfate (6.6 mg/kg [3 mg/lb], IV), and flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg [0.045 mg/lb], IV).

The hair over the ventral abdomen and the portal sites are prepared for surgery with chlorhexidine surgical scrub solution alternated with sterile gauze soaked in saline (0.9% NaCl) solution. Whenever practical, a presurgical scrub is performed to remove all organic debris followed by 10–15 minutes of contact time with the antibacterial preparation prior to induction. The rectum is manually evacuated and the uterus is confirmed to be empty and prepared for surgery. The horse is then led into the induction room for general anesthesia.

Instrumentation

| 1 | 57-cm 30° laparoscopic telescope |

| 1 | Video camera, monitor, light source, insufflator |

| 2 | 5-mm universal grasping forceps |

| 4 | 5- to 12-mm laparoscopic cannula assemblies |

| 2 | 10-mm laparoscopic cannula assemblies |

| 1 | 10 × 32 mm Semm claw forceps |

| 1 | 10-mm vessel-sealing device (LigaSure) |

| 2–3 | Doyen clamps |

Items to have available

- Colon clamp

- Ligating loops

- Hemoclips

- Staples

- Laparoscopic suction lavage tip and trumpet valve

- Specimen bag

- Extra 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopic cannula assemblies

- 5-mm laparoscopic scissors

- Laparoscopic monopolar and bipolar electrosurgery instruments

Surgery

After the horse is induced, it is placed in dorsal recumbency on a laparoscopic operating table (Figure 30.3). The rear limbs are secured in a caudally raised neutral position with leg braces. The tail is attached to the table lift with a nylon rope (Figure 30.4). A chest pad is used to brace the front of the horse (Figure 30.5). The tail rope and the chest brace are to ensure the horse does not slide down the table when it is tilted. A urinary catheter is aseptically placed for the duration of the operation. A final lavage of the uterus is performed at this time if needed. The surgical site is again scrubbed in preparation for sterile draping.

Figure 30.4 The horse on the laparoscopic operating table is secured with a tail rope to prevent displacement during Trendelenburg positioning.

Figure 30.5 The horse on the laparoscopic operating table is secured with a chest pad to prevent displacement during Trendelenburg positioning.

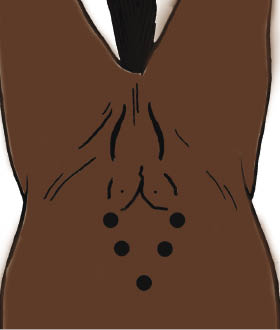

After draping and laparoscopic equipment setup, a laparoscope portal and four instrument portals are required to perform an ovariohysterectomy (Figure 30.6). The laparoscope is inserted at the umbilicus. Two instrument portals are placed on each side of the abdomen in the axial half of the rectus muscle to avoid the deep epigastric vessels (Ragle et al. 1998) (Figure 30.7). The cranial portals are halfway between the umbilicus and the mammary gland. The other portals are several centimeters lateral and caudal to the cranial portals.

Figure 30.6 Typical portals required for laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy

(adapted from Ragle 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree