Chapter 19 OVARIAN CYCLE AND VAGINAL CYTOLOGY

THE OVARIAN CYCLE

Onset of Puberty

Breed has a significant effect on the timing of a dog’s first estrus. Generally, bitches exhibit their first cycle several months after they achieve adult height and body weight. There is, however, considerable variation within a breed as well as between different breeds. The Beagle, for example, usually exhibits her first proestrus between 7 and 10 months of age. Even in a controlled laboratory environment, the first proestrus may occur as early as 6 months of age or as late as 13 months (Concannon, 1987). Thus it is reasonable to advise owners that some small breeds enter their first heat between 6 and 10 months of age. Although a large-breed bitch may also begin her first proestrus before 1 year of age, some normal large-breed dogs may not begin to cycle until 18 to 24 months of age. A good deal of individual and breed variation is reported. This natural variability, coupled with cycles referred to as silent heats, adds to a veterinarian’s or owner’s inability to predict the timing of a first season (estrus) (Concannon, 1980; Evans and White, 1988; Johnston, et al, 2001).

Silent heat is simply one that goes unnoticed by the owner because little vulvar swelling, bleeding, attraction of males, or behavioral change may be associated with estrus in a young bitch. The owner’s experience, hair length of the dog (vulvar bleeding is easier to see in a short-haired dog), cleanliness of the dog (one that licks a great deal is more apt to hide bleeding), and presence of a male dog in the home are just a few of the variables that determine the ease with which an owner may notice estrus (Concannon, 1980). We tend not to begin to evaluate a female dog clinically for failure to experience an ovarian cycle until she is at least 2 years of age. (See Infertility, Chapter 24.) The ideal age for breeding is between 2 and 6 years. First breeding is recommended during the second or third estrus, after an owner has witnessed at least one complete normal ovarian cycle.

Intervals Between Ovarian Cycles

The “average” bitch begins proestrus approximately every 7 months. Thus, an ovarian cycle would begin at least once in every month of the year during a bitch’s life if this schedule were maintained. There is a tendency to vary somewhat. The common interestrus interval (the period from the end of standing heat to the beginning of the following proestrus) is 5 to 11 months, with the normal interestrus interval as short as 3.5 months and as long as 13 months (Concannon, 1987). Interestrus intervals more frequent than every 4 months, however, are often associated with infertility, and those greater than every 12 months may be associated with sufertility or infertility. Breed and individual variability can be striking. The German Shepherd dog, for example, is one breed that often cycles every 4 to 4.5 months and yet maintains fertility. Rather than relying on knowledge concerning individual breeds, we use the 5- to 11-month interval as normal. It also appears that most dogs 2 to 6 years of age are relatively consistent in cycle length as well as in the duration of each phase. The obvious exceptions to the 7-month average normal interestrus interval are the African dog breeds such as the Basenji. These dogs cycle once yearly. Litters of this breed are typically whelped in December, with January and November following as likely months of births.

As dogs advance beyond the optimal breeding age (approximately 7 years), various changes are likely to occur, including progressive lengthening in the duration of the interestrus interval, reduction in litter size, increases in congenital birth defects, and problems at parturition. In one study, mean interestrus intervals increased from approximately 240 days to more than 330 for Beagle bitches after they reached 8 years of age, but healthy dogs continue to experience ovarian cycles throughout life (Anderson and Simpson, 1973).

Phases of the Ovarian Cycle

There are four phases of the canine ovarian cycle.

Proestrus

DURATION.

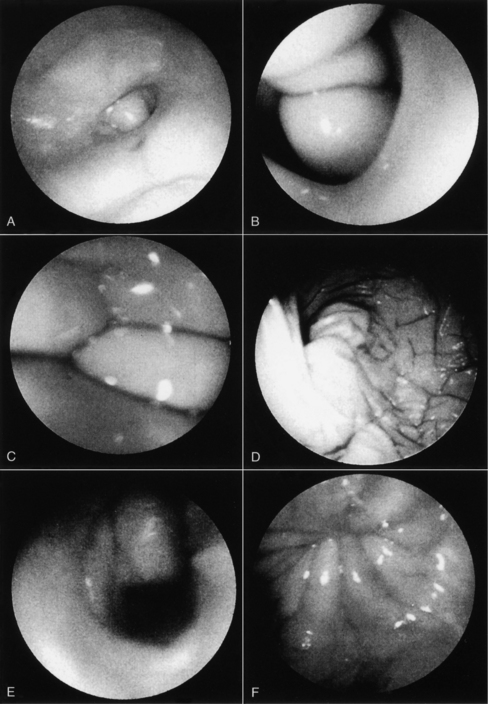

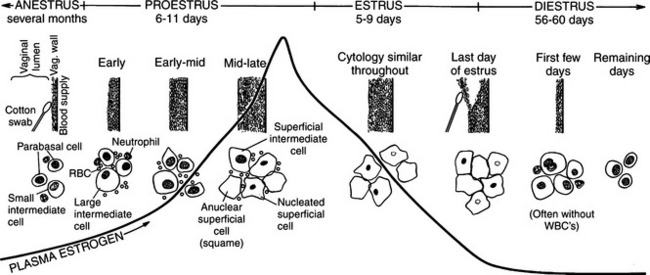

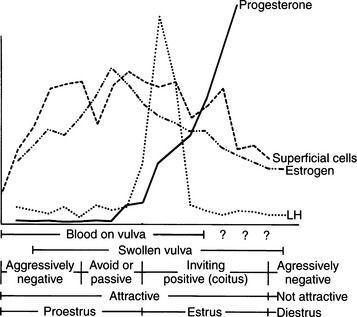

Proestrus is usually, and most reliably, defined as beginning when vaginal bleeding is first seen and ending when the bitch allows a male dog to mount and breed. Additional criteria used in defining the onset and completion of proestrus include changes in the appearance of the vaginal mucosa viewed endoscopically (Fig. 19-1) or changes seen on exfoliative cytology of vaginal epithelial cells (Fig. 19-2). Less reliable criteria used in describing the onset of proestrus include enlargement of the vulva, attraction of males, and changes in behavior toward males (Fig. 19-3).

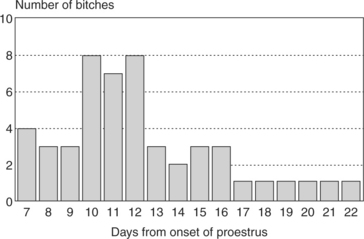

The length of time from the onset of proestrus to the time of first breeding is usually 6 to 11 days, with an average of 9 days. However, variations within “normal” can be extreme (i.e., as brief as 2 or 3 days to as prolonged as 25 days) (Fig. 19-4). These extremes in normal duration of proestrus can be confusing, and their significance is discussed in greater detail in association with the evaluation of female infertility (Chapter 24).

CLINICAL SIGNS.

Early proestrus behavior includes attraction of males, in part due to pheromone secretion (Goodwin et al, 1979). An increase in playful/teasing activity with discouragement of any mounting attempt by a male is common (Jeffcoate, 1998). This unwillingness to breed may involve antisexual growling, moving away, baring the teeth, and snapping. The bitch may also keep her tail tight against the perineum, between the rear legs and covering the vulva. This initial behavior pattern gradually changes as proestrus progresses. The female usually becomes more receptive, as demonstrated by actually seeking and playing with males. The response by the bitch to male mounting attempts progressively becomes more restrained, as she prevents mounting by retreating, crouching, or lying down. In late proestrus, the behavior of the bitch may be described as passive, and she may sit quietly when mounted, with or without intermittent displays of tail deviation and lordosis.

Proestrus is typically but not always associated with varying quantities of bloody vaginal discharge. Vaginal bleeding begins as diapedesis of erythrocytes through the endometrium and subepithelially as capillaries rupture within the endometrium. This blood seeps through a slightly relaxed cervix and enters the vaginal vault. Small numbers of erythrocytes may also originate from the vaginal mucosa, since erythrocytes have been observed in vaginal smears obtained from proestrus bitches that had been previously hysterectomized (Johnston et al, 2001). Rapid changes in thickness and development of the vaginal mucosa and the endometrium are responses to follicular estrogen secretion. The volume of bleeding and bloody vaginal discharge vary from bitch to bitch.

Bitches that keep themselves clean through licking may present a difficult challenge in detecting proestrus. Short-haired dogs without tails (e.g., German Short-Haired Pointers) can be contrasted with long-haired dogs with flowing tails (e.g., Newfoundlands). Obviously, vaginal bleeding associated with proestrus is easier to detect in some breeds than in others. Occasionally, a grayish mucoid-like vaginal discharge is observed before actual bleeding or swelling of the vulva. Classically, dogs cease vaginal bleeding as proestrus proceeds into estrus. In these bitches the bloody discharge fades and becomes transparent to straw-colored. However, changes in color of the vaginal discharge are inconsistent, with some bitches showing bloody discharge throughout proestrus, estrus, and into diestrus, whereas others bleed little or only at the beginning of proestrus.

HORMONAL CHANGES AND OVARIAN ANATOMY.

The bitch in proestrus is under the influence of estrogen. This estrogen is synthesized and secreted by developing ovarian follicles. Proestrus is the phase of estrogen dominance in the bitch (see Fig. 19-2). FSH and LH pulses are released in concordance in late anestrus, and progression from anestrus into proestrus is associated with an increase in the secretion of FSH with a concomitant rise in LH secretion (Kooistra and Okkens, 2000). Follicles that develop at a time coinciding with gonadotropin stimulation mature and attain the capacity for estrogen synthesis and secretion. The secreted estrogen results in vaginal discharge, attraction of males, and uterine preparation for pregnancy. The potent effects of estrogen can be demonstrated in the ovariohysterectomized female, which can easily be brought into a classic proestrus state (without vaginal bleeding) by administration of estrogens (Concannon, 1987). Estrogen alone usually does not result in breeding activity. Breeding in the dog is typically associated with a serum combination of decreasing estrogen and increasing progesterone concentrations. Estrogen alone usually does not cause behavioral estrus (Leedy, 1988).

The appearance of the ovaries has been monitored during proestrus with ultrasonography. Ovaries of bitches in anestrus can be visualized as structures with an echogenicity equal to or slightly greater than that of the renal cortex. Follicles appear as focal hypoechoic to anechoic rounded structures. Ovaries are easier to identify as follicular development progresses. Ovarian size increases throughout proestrus (England and Allen, 1989a, 1989b; Wallace et al, 1992).

Decreasing plasma estradiol concentrations stimulate the onset of estrus. During the subsequent 5 to 20 days, plasma estradiol concentrations taper progressively to basal levels. Therefore, proestrus is a phase of rising and then stable serum estrogen concentrations, and estrus is a phase of decreasing serum estrogen concentrations. “Basal” serum estrogen concentrations are observed in anestrus and in diestrus, although variations within individual dogs may be observed (Olson et al, 1982). Concentrations of testosterone increase in the serum of bitches during late proestrus, reaching concentrations of 0.3 to 1.0 ng/ml at the time of the LH surge that occurs in early estrus (Olson et al, 1984).

ANATOMY OF THE UTERUS, OVIDUCTS, AND MAMMARY GLANDS.

Several “estrogen-target” tissues are affected by increases in serum estrogen concentrations during proestrus. These include growth of mammary gland ducts and tubules, proliferation of oviductal fimbria, thickening of oviducts, elongation of uterine horns, thickening of endometrium, increased myometrial sensitivity, enlargement of the cervix, elongation and edema of the vagina, proliferation of the vaginal wall, and synthesis of hepatic steroid-metabolizing enzymes (Concannon and DiGregorio, 1986; Concannon, 1987). The preparation for implantation in the endometrium includes a remarkable increase in wall thickness and glandular activity, changes that are associated with bleeding. This uterine hemorrhage is the primary source of vaginal bleeding associated with proestrus and, in some bitches, estrus.

VAGINAL ANATOMY AND ENDOSCOPY.

Increasing estrogen concentrations thicken the vaginal wall, which protects the bitch from the traumatic effects of breeding. The vaginal lining in anestrus is only a few cell layers thick and is relatively fragile. The basal or germinal cell layer is orderly, and the less orderly overlying cells are situated in rather close proximity to the blood supply present below the germinal layer. The increasing estrogen concentrations associated with proestrus cause rapid multiplication in the number of cell layers lining the vaginal vault, resulting in a wall 20 to 30 layers thick by the end of proestrus (Johnston et al, 2001). Thus intromission of the penis into the estrogen-primed vaginal vault is not harmful to the female.

This increased number of cell layers moves the cells lining the lumen further from their blood supply, causing the death of those cells. These dead cells function as a less sensitive and less fragile tissue. Fragility decreases not only because of increased cell layers, but also because of the development of keratin precursors within these cells. This nuclear material is similar to that found in fingernails. Thickening of the vaginal mucosa can be easily recognized with cytology (see Fig. 19-2).

Thickening in the vaginal mucosa, easily demonstrated with cytology, may also be detected with vaginoscopy. The procedure is simple and well tolerated by nonsedated bitches that have normal vaginovestibular anatomy, but does require some practice and experience. Before inserting any vaginoscope, one should first perform a digital examination of the vaginal vault to confirm that no stricture is present (see Chapter 25). The mid- to anterior vagina can be visualized using a rigid pediatric proctoscope or flexible endoscope. The less expensive proctoscope is an excellent tool for this purpose. Otoscopes are completely inadequate for viewing anything but the “vestibule” of the vagina. The vaginal mucosa is flat in anestrus because relatively few cell layers are present (see Fig. 19-1).

During proestrus, the mucosa appears markedly rounded, edematous, smooth, and shiny (Jeffcoate, 1988). Vaginal folds are pink and billow out into the lumen as a result of fluid retention, resulting in an inability to visualize the lumen (Goodman, 2001). The decreasing estrogen and increasing progesterone concentrations associated with the final 1 to 3 days of proestrus (or the first days of estrus in some bitches) cause edema in the vaginal mucosa to subside, and the stretched luminal surface becomes progressively wrinkled (see Fig. 19-1). This is referred to as crenulation. Initial vaginal crenulation, observed as this subtle wrinkling of the mucosa, appears within 24 hours of the preovulatory LH surge (Lindsay and Concannon, 1986; Concannon, 1987; Jeffcoate, 1998).

The LH surge, in turn, precedes the onset of ovulation by approximately 24 to 48 hours. Breeding should begin at this time. The mucosa becomes progressively more crenulated, the lumen more obvious, and the vaginal folds more flattened as the edema diminishes. This wrinkling is most obvious during the fertile period 4 to 7 days after the LH surge. By diestrus the mucosa is flat and variegated. Further, because the protective thickened layers of epithelium have disappeared, the mucosa once again becomes fragile and superficial hemorrhage may be associated with vaginoscopy (Goodman, 2001). With practice and observation of individual variation in this process, vaginoscopy becomes a useful adjunct when attempting to best time a breeding.

Classification of Vaginal Cells

GENERAL BACKGROUND.

Nomenclature of vaginal cells is based on cell morphology. Older literature refers to keratinized versus nonkeratinized cells and/or to cornified versus noncornified cells. Some species actually develop a hard keratin lining of the vaginal tract as a result of increasing circulating estrogen concentrations. The bitch, however, does not develop a “cornified” vaginal lining, which explains the different nomenclature used in describing alterations in canine vaginal cells due to estrogen influences. Different cell types represent stages of cell death. As healthy round vaginal cells die, they become larger and more irregular in shape. The nuclei within vaginal epithelial cells also undergo changes that reflect cell death: the nucleus becomes progressively smaller, then pyknotic, before eventually disintegrating, leaving a nuclear “ghost” and then an anuclear cell (see Fig. 19-2).

PARABASAL CELLS.

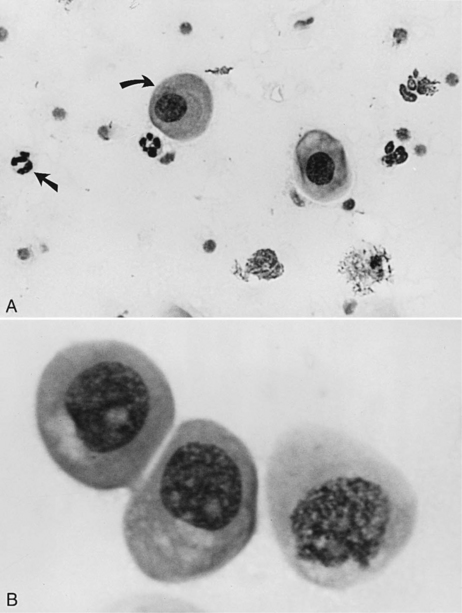

Parabasal cells are the healthiest and smallest of the vaginal cells. They are round or slightly oval and have a large vesiculated nucleus and relatively small amounts of cytoplasm. They usually stain well with Wright-Giemsa stain or some of the rapid stains (Diff-Quik, American Scientific Products, McGraw, IL). These cells are exfoliated from near the germinal cell layer, close to the underlying blood supply (Fig. 19-5).

INTERMEDIATE CELLS.

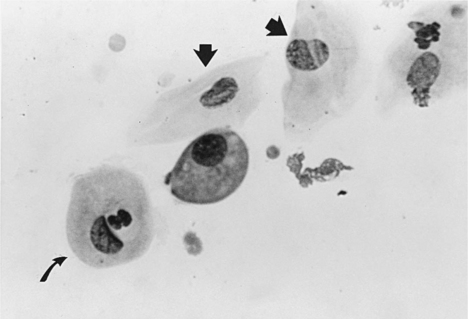

Intermediate cells vary in size from slightly larger than parabasal cells to twice their size. These cells have smooth, oval to rounded irregular borders and a nucleus that is vesiculated but generally smaller than those found in parabasal cells (Fig. 19-6). This change in morphology reflects the first step in cell death: cells appear larger, have relatively larger amounts of cytoplasm, and have smaller nuclei. For descriptive purposes they are classified as small intermediate cells and large intermediate cells.

SUPERFICIAL CELLS.

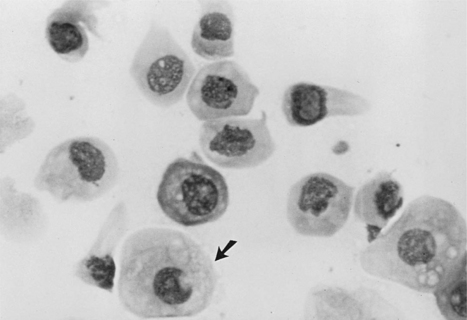

Superficial cells are dead cells that line the vaginal lumen of bitches in estrus. They are the largest cells identified on vaginal cytology. These cells have sharp, flat, angular cytoplasmic borders and small, pyknotic, fading nuclei or no nuclei (Fig. 19-7).

SUPERFICIAL-INTERMEDIATE CELLS.

These are vaginal cells that appear to have relatively healthy vesiculated nuclei but also have the angular, sharp, flat cytoplasmic border typical of superficial cells (Olson et al, 1984b; Olson, 1989) (Fig. 19-8). The superficial-intermediate cell provides evidence for potent estrogen effect on the vaginal lining, but not quite the full effect. Full estrogen effect is associated with superficial cells and anuclear squames. Vaginal exfoliative cytology may not progress beyond the presence of superficial-intermediate cells at the peak of estrogen effect. No study has demonstrated associations between failure to develop superficial cells on vaginal cytology and subsequent breeding or fertility problems.

ANUCLEAR SQUAMES.

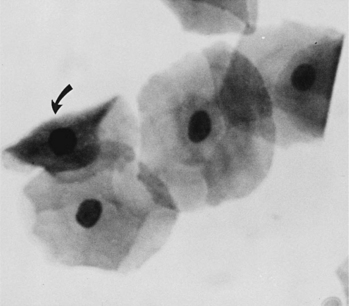

These large, dead, irregular vaginal cells with no nuclei represent the end of a process that began with healthy round parabasal cells. This cell death is caused by the thickened vaginal lining. As the vaginal wall thickens in response to increases in serum estrogen concentrations, from several cell layers to 20 to 30 cell layers, those cells lining the lumen become far removed from their blood supply and their death is inevitable (see Fig. 19-2). These cells are also called anuclear superficial cells. They are large cells with flat, angular borders (Fig. 19-9). These are the cells that have also been called “fully cornified” or “fully keratinized” cells.

METESTRUM CELLS.

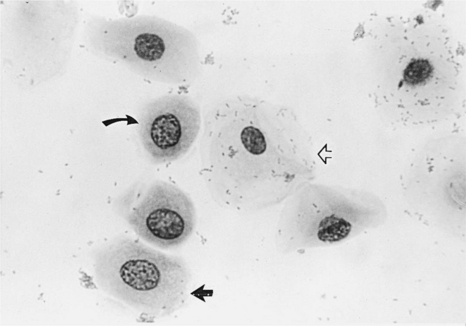

Metestrum cells are usually large intermediate vaginal cells that appear to have one or more neutrophils contained within their cytoplasm (Fig. 19-10). As described below, metestrum cells are usually seen in the vaginal smear from a bitch in early diestrus or one with vaginitis. Rarely, such cells are observed in early proestrus.

Vaginal Cytology in Proestrus

EARLY PROESTRUS.

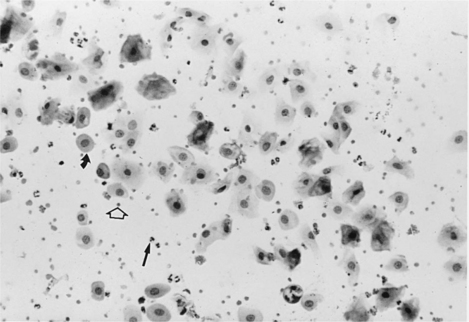

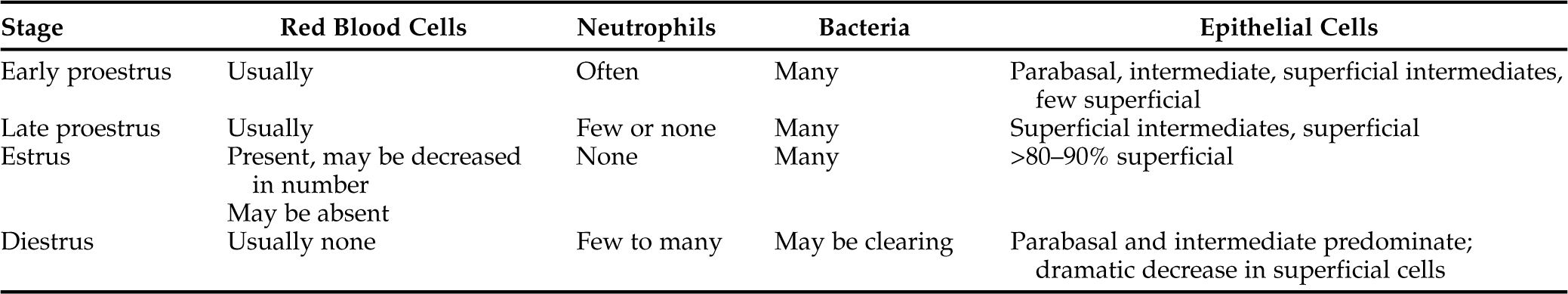

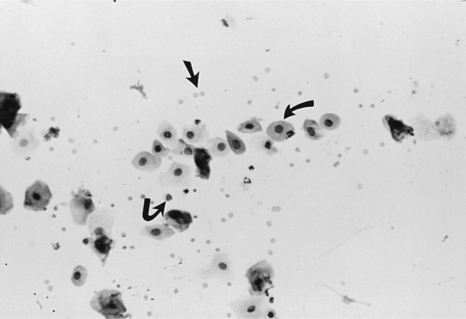

The vaginal smear from a bitch in early proestrus is similar to that from a bitch in anestrus, with one difference: the presence of blood within the vagina derived primarily from a rapidly developing endometrium (see Fig. 19-2). In addition to varying numbers of red blood cells, the vaginal smear usually contains numerous parabasal, small, and large intermediate vaginal epithelial cells. Neutrophils are common in varying numbers, and bacteria may be present in small to large numbers (Fig. 19-11; Table 19-1). The background of these smears is often granular or “dirty” in appearance, owing to the presence of viscous cervical and vaginal secretions that appear to take a slight amount of stain.

MID-PROESTRUS.

The first evidence of continued estrogen effect on the reproductive tract is visualized in the vaginal cytology. This includes (1) disappearance of neutrophils, (2) appearance of the red blood cells, and (3) progressively increasing percentage of superficial cells replacing the smaller parabasal and intermediate cells. White blood cells are believed to enter the vaginal lumen through the mucosal wall. With the dramatic thickening in the wall caused by estrogen, neutrophils are unable to penetrate this barrier and enter the lumen. Neutrophils are not normally visualized in vaginal smears from bitches between mid-proestrus and the start of diestrus Fig. 19-12).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree