Chapter 80Other Soft Tissue Injuries

Rupture of the Fibularis (Peroneus) Tertius

Anatomy

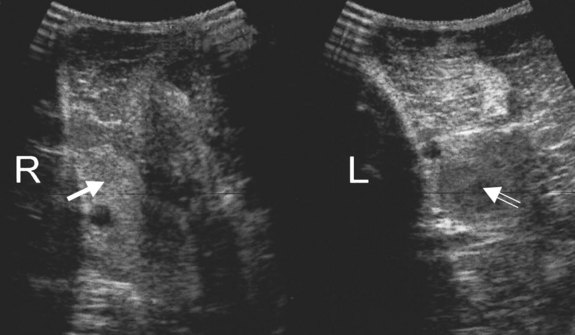

The fibularis tertius is the most echogenic structure on the craniolateral aspect of the crus and is identified readily by ultrasonography as a well-demarcated hyperechogenic structure relative to the surrounding muscles (Figure 80-1).

History and Clinical Signs

If the limb is picked up and pulled backward, the hock can be extended gradually and “clunks” into complete extension while the stifle remains flexed. A characteristic dimple appears in the contour of the caudal distal aspect of the crus (Figure 80-2). If rupture is only partial, or if lameness is chronic and some repair has taken place, clinical signs may be less severe and the diagnosis less obvious.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of rupture of the fibularis tertius is based on the pathognomonic clinical signs. The site of rupture can be identified with ultrasonography (see Figure 80-1). The normally echogenic structure is not clearly identifiable and may be replaced by a region that is hypoechoic relative to the surrounding muscles. In horses with chronic injuries the surrounding muscles may become hypertrophied. Usually no associated radiological abnormalities are apparent in adult horses, although avulsion fracture of the origin has been described in foals.