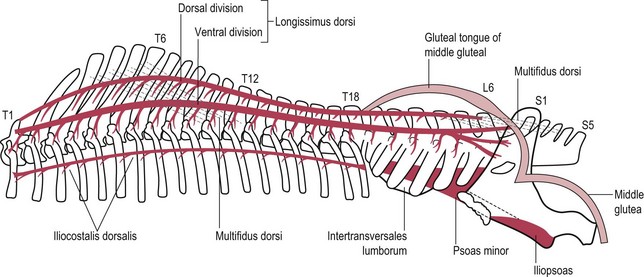

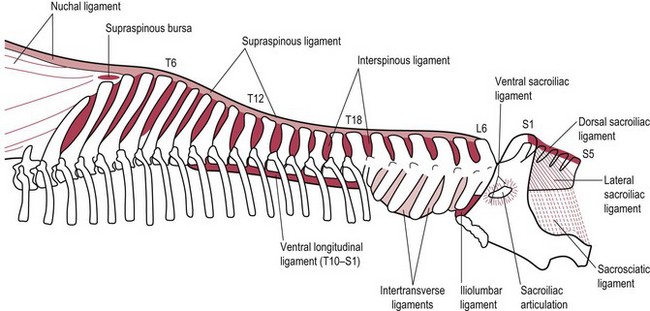

Chapter 18 18.1 Anatomy of the horse’s back 18.2 Diagnostic approach to diseases of the horse’s back 18.3 Disorders of the horse’s back – conditions that may present as a back problem 18.4 Vertebral column deformities 18.7 Impingement and overriding of the dorsal spinous processes (‘kissing spines’) 18.8 Other conditions of the spine 18.10 Treatment of back conditions 18.12 Caudal aortic or iliac artery thrombosis There are usually 29 vertebrae in the back (T18, L6, S5); variations in the vertebral back formula are not unusual in clinically normal horses (e.g. 17 thoracic and 7 lumbar vertebrae). The vertebrae are held in place by a series of ligaments (Figure 18.1). The supraspinous ligament is the caudal continuation of the nuchal ligament and inserts at the tip of every thoracolumbar dorsal spinous process. The main muscles of the back include the largest muscle in the body, the longissimus dorsi, and the powerful gluteal muscles (Figure 18.2). The neck, consisting of seven vertebrae, is most frequently associated with neurological disease and is covered in Chapter 11. • The type of work: the horse may not be suitable for the work expected of it; certain forms of exercise may prove more problematic, e.g. jumping. • Temperament: owners of horses with a genuine back problem frequently report that the horse has become ill-tempered, fractious or reluctant to work. • Acute or chronic problem: if the problem has arisen following recent trauma, details of the accident may help to localize the site of pain, although more typically no such incident will have been observed. • Position of limbs: the horse may no longer straddle when urinating or defecating; there may be reluctance to bear more weight on one hind limb (e.g. during shoeing). • Bucking: if the history includes episodes of bucking, the safety of any riders should be paramount, regardless of whether the signs are due to pain in the horse’s back or are behavioural; this may limit the clinical investigation, and this should be explained to the owner at the outset. Conformation: General condition should be noted. Abnormal curvature of the back is assessed: i.e. lordosis (ventral deviation), kyphosis (dorsal deviation) or scoliosis (lateral deviation of spine due to spinal malformation or asymmetric muscle spasm). Conformational defects of the limbs (e.g. straight hocks characteristic of proximal suspensory disease) may suggest bilateral hind limb lameness. • Palpate soft tissues and summits of dorsal spinous processes (DSPs) for pain, heat or swelling. • Assess flexibility of the back by stimulation reflex extension (dipping), flexion (arching) and lateral bending. This is done by running a blunt probe along the midline of the back from the withers to the sacroiliac region, and laterally from midline. It is important to note that a high range of reflex back movements indicates a normal, pain-free horse, although these movements are often interpreted as a sign of pain. A horse with back pain braces its back rigidly and shows clear signs of resentment. • Similarly, pressure applied upwards onto the ventral aspect of the sternum should induce a normal horse to arch its back without signs of discomfort. • Apply pressure to both tubera coxae and tubera sacrale; pain here may indicate fracture of the ilium or a problem in the pelvic or sacroiliac region. • The horse is walked and then trotted in-hand for lameness evaluation. • Overt lameness or gait abnormalities should be identified; many horses with suspected back pain suffer from hind limb lameness. If present, this should be investigated first as described in other chapters. • Positive hind limb flexion test(s) suggest lameness rather than back pain. • Back pain often results in a reduced length of stride of the hind limbs and less hock flexion, but the same signs are seen in chronic hind limb lameness. • Turning the horse tightly in both directions may provoke longissimus dorsi spasm due to pain caused by lateral spinal flexion. • There may be reluctance to move backwards, with the head being raised and back muscle spasm because this maneuver may provoke spasms of the back muscles. Clinical biochemistry: The blood concentrations of the muscle-derived enzymes creatinine kinase (CK) and aspartate transaminase (AST) are measured before, immediately following, and about 12 hours after 10–20 minutes of exercise (trotting and cantering). Significant rises (by more than 100–200%) suggest an exertional rhabdomyolysis. Radiography (see Chapter 25): Powerful equipment (150 kVp/300 mAs) is required for a comprehensive radiographic examination of the thoracolumbar spine. Smaller portable units are capable of imaging the tips of the dorsal spinous processes (DSPs) from T6 to the cranial lumbar region, but not the vertebral bodies or dorsal intervertebral articulations, a common site of painful osteoarthritis. Typical exposure values are 80 kVp/30 mAs for the DSPs of the mid-back region. Scintigraphy (see Chapter 25): Bone scanning using radioactive technetium labelled with methylene diphosphonate indicate areas of abnormal skeletal metabolic rate due to trauma (e.g. fracture), inflammation or infection (Figure 18.3). A gamma camera is used, and the examination can be carried out on standing, sedated horses, but images of better quality are obtained under general anaesthesia. Ultrasonography (see Chapter 25): This technique can be used to evaluate soft-tissue structures such as the supraspinous, interspinous and dorsal sacroiliac ligaments, and is essental when directing a needle towards deep structures such as the dorsal intervertebral articulations. Its value as a routine screening tool in cases of suspected back pain, for example to detect muscle abnormalities, remains unproven. Local analgesia: This is most useful to confirm the suspected site of pain due to DSP impingement (‘kissing spines’).

Orthopaedics 4. The back and pelvis

18.1 Anatomy of the horse’s back

18.2 Diagnostic approach to diseases of the horse’s back

History

Examination at rest

Examination at exercise

Aids to diagnosis