Elizabeth A. Giuliano

Ocular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Tumors affecting the orbit, eyelid, or globe often manifest initially as signs of ocular discomfort or mucopurulent discharge, but they can be identified before the development of serious ocular or periocular complications through careful ophthalmic examination. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common neoplasm of the equine eye and ocular adnexa and is the second most common tumor affecting the horse overall. Squamous cell carcinoma may involve any or all of the corneoconjunctiva, bulbar conjunctiva, third eyelid, and eyelids. The biologic behavior of SCC varies depending on location. Tumors are typically locally invasive and slow to metastasize. Metastasis to local lymph nodes, salivary glands, and thorax can occur. A poorer prognosis has been associated with SCC involving the eyelid, compared with SCC of the nictitating membrane, nasal canthus, or limbus.

Several risk factors have been associated with development of SCC. Ultraviolet light exposure is believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of SCC in horses and other species. Exposure to ultraviolet light can lead to mutations in the p53 gene, an important regulator of cell growth and proliferation, with resulting development of SCC. Additionally, a breed predilection exists for draft horses, Appaloosas, and American Paint Horses. Finally, a higher frequency of ocular SCC has been reported in horses lacking pigmentation around the eye, such as Pintos.

Examination and Diagnostic Procedures

Given the sometimes slow-growing nature of ocular SCC and the overall small area this tumor may occupy, compared with the total body surface area of a horse, this neoplasm is often not detected by the owner or general practitioner until it is advanced. For this reason, it is recommended that the equine practitioner perform a complete ophthalmic examination as part of any routine health check or prepurchase examination. When presented with any ophthalmic abnormality, preservation of vision and ocular comfort should guide the diagnostic and therapeutic plan.

The horse should first be examined from a distance to facilitate assessment of facial symmetry and eyelash positioning. One of the first clinical signs observed with ocular pain in horses is ventral deviation of the eyelashes on the affected side. The regional lymph nodes and parotid salivary glands should be palpated. A room with controlled lighting is ideal for examination of the globe and periocular structures and should be used for any animal ophthalmic exam; however, access to adjustable lighting is not always possible in equine practice. A dark blanket placed over the examiner’s and horse’s heads helps create a darkened environment. The complete ophthalmic examination and derivation of a minimum ophthalmic database should be undertaken during all ophthalmic examinations with few exceptions. Components of the minimum ophthalmic database include menace response, direct and consensual pupillary light reflex, palpebral reflex, Schirmer tear test, fluorescein stain, and tonometry (Box 149-1). Tonometry must be performed with caution in any horse with a deep corneal ulcer to avoid globe perforation. Retropulsion and assessment of ocular motility are often helpful in horses with suspected orbital tumors or intraocular tumors with extrascleral extension. Retropulsion also enables the practitioner to more thoroughly examine the third eyelid (nictitans), a common site for SCC in horses. To better determine prognosis and plan treatment, gentle digital palpation of the orbital rim is essential. This is best accomplished with the horse sedated. Using a gloved finger lubricated with a small volume of ophthalmic ointment, the examiner inserts the finger into the conjunctival fornix and palpates the entire orbital rim through the mucosa of the upper and lower fornices. When SCC has invaded local surrounding tissues, the orbital rim often cannot be felt in areas of neoplastic infiltration.

After a complete ophthalmic examination has been performed, diagnostic imaging may be indicated, such as ocular ultrasound, skull radiographs, and computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. These modalities are especially helpful in horses with SCC in which evidence of bony extension is likely to alter the prognosis or surgical planning. Fine-needle aspiration of the regional lymph nodes, parotid salivary gland, or both should be performed when lymphadenopathy is detected or if there is local invasion of tumor. Definitive diagnosis of SCC should always be obtained on the basis of biopsy and histologic diagnosis. Consultation with or referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist may be helpful. Members of this specialty group can easily be located at www.acvo.org.

Clinical Features of Ocular and Periocular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

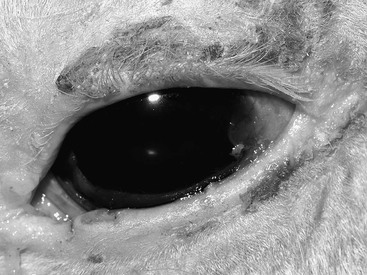

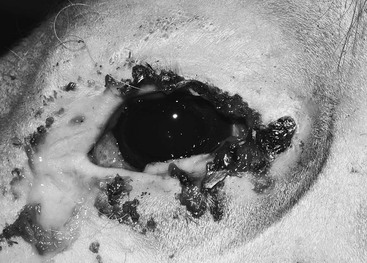

Clinical features of SCC and its precursor lesions, which include actinic keratosis, epithelial dysplasia, chronic keratosis, and carcinoma in situ, are variable. Although SCC may arise from any location on the globe or periocular tissues, commonly affected sites include the temporal region of the limbus, leading edge of the nictitans, and eyelid margins. Classic features of this tumor type include pink to white, raised, friable, vascularized lesions with a cobblestone- or cauliflower-like appearance (Figures 149-1 to 149-4). Necrotic tumor surfaces with a white “cake frosting” appearance from secondary bacterial infection may impart a fetid odor to the lesion.

Proliferative SCC arising from the eyelid and nictitans may be pedunculated with a broad base (see Figure 149-3). Ulcerated forms of this tumor typically cause erosion of the eyelid margins, medial canthus, or nictitans (see Figure 149-4). Both proliferative and ulcerated forms of SCC may be present concurrently. If left untreated, local orbital invasion can ensue (Figure 149-5), resulting in substantial ocular discomfort and necessitating exenteration, which is removal of the orbital contents and eyelids. Differential diagnoses for SCC include papilloma, habronemiasis, eosinophilic conjunctivitis, foreign body granuloma, amelanotic melanoma, cutaneous mastocytoma, and other causes of blepharitis or keratoconjunctivitis. Although most SCCs have the described typical appearance at initial evaluation, definitive histologic diagnosis should always be obtained.

Treatment

Ocular and periocular tumors in horses represent a unique therapeutic challenge to equine practitioners as a consequence of both anatomic location and the unique characteristics of SCC. Reconstructive surgery to remove extensive masses affecting the globe or adnexa while maintaining cosmesis and vision is challenging and, at times, impossible. The eye is a delicate organ and is prone to visual compromise from secondary inflammation. Special instrumentation coupled with skill in microsurgical techniques is needed for removal of corneal or conjunctival masses with the best chance for a visual outcome. Eyelids act as the primary “windshield wiper” of the cornea, and, as such, any irregularity in eyelid shape or contour can result in chronic keratitis, ulceration, and discomfort. Preservation of eyelid function must be balanced with the need for adequate tumor resection. Eyelid tumors in horses are often not amenable to complete excision. Eyelid reconstruction surgery, such as the H-plasty or bucket-handle procedures commonly performed in small animals, is nearly impossible in horses because of the tight adherence of periocular skin to underlying fascia and bone.

Tumor characteristics also play a role in treatment outcome for SCC. Surgical excision alone for ocular or periocular SCC carries a high recurrence rate and often results in incomplete tumor resection if the mass is larger than 1 cm in diameter. For this reason, veterinary ophthalmologists rarely recommend sharp dissection alone. Various ancillary treatments have been reported, including cryosurgery, hyperthermia, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and laser ablation (Table 149-1). Reported success rates vary, and the published literature on ophthalmic SCC in horses includes many reports with low case numbers and poor long-term follow-up. Additionally, the extent of tumor involvement is not always well characterized, leading to publication of unrealistically positive outcomes in some studies that included cases with superficial tumors for which virtually any type of treatment may have yielded favorable results.

TABLE 149-1

Summary of Treatments Used in Horses With Ophthalmic Squamous Cell Carcinoma*

| Treatments | Recurrence Rate (%) | Follow-Up (months) | References |

| Surgery alone | 42-62 | 12-48 | < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|