CHAPTER 21

Occupational Hazards and Safety Issues

Mastery of the content in this chapter will enable the reader to:

• Describe methods used to prevent the transmission of zoonotic diseases.

• Identify the hazards associated with veterinary medicine.

• List methods used to lift equipment and animals appropriately.

• Define the role of the Occupational Health and Safety Administration.

• Develop a hospital safety manual.

• Discuss and implement a training program.

• Describe how to prevent fires.

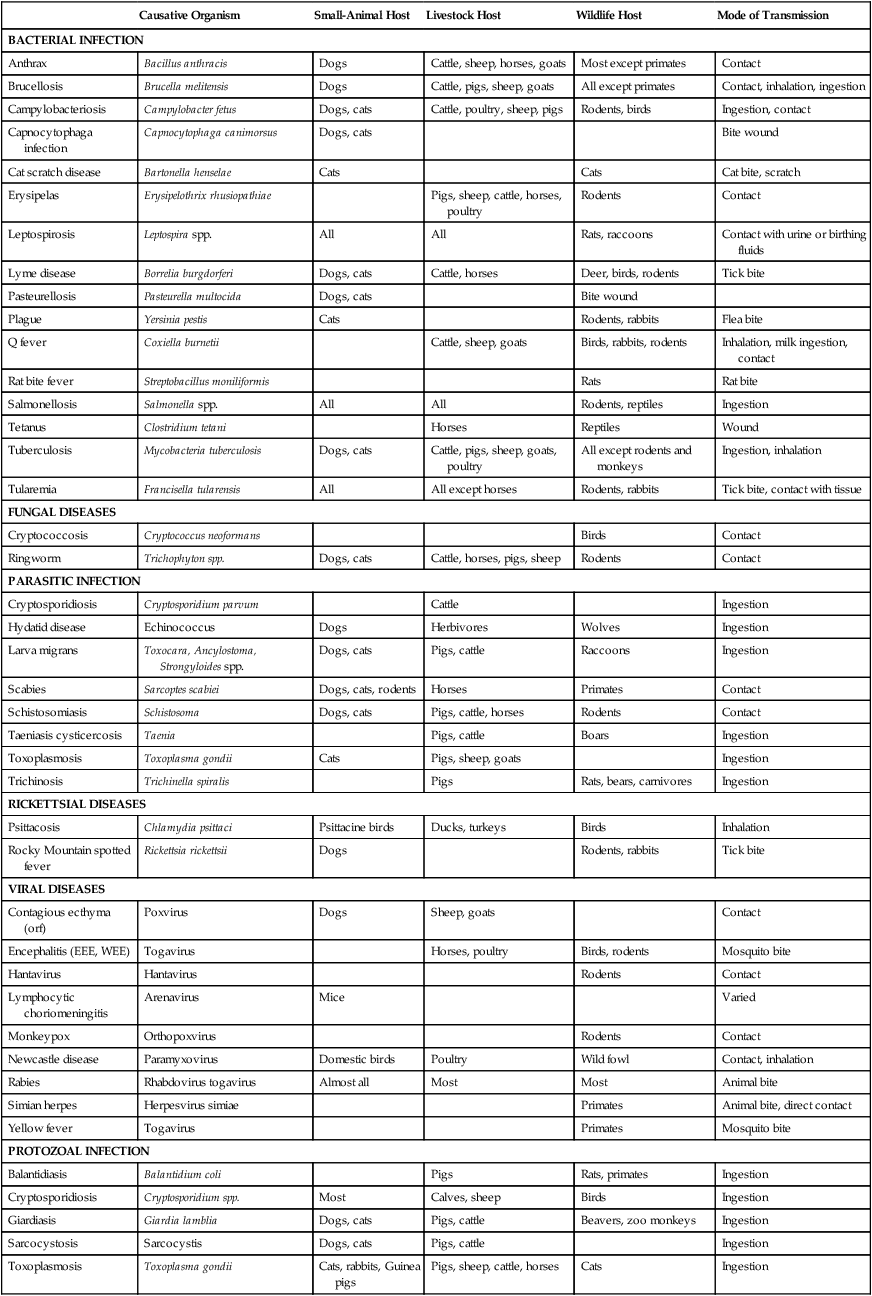

ZOONOTIC DISEASES

Zoonoses are defined as diseases that may be directly or indirectly transmitted to humans from wild or domesticated animals. More than 1400 diseases are currently known to be zoonotic, of which 60% are caused by pathogens known to cross species lines. The need to educate the public and veterinary practice team members is imperative because veterinarians may be held liable for the transmission of such diseases. Veterinarians play a vital role in public health and control of zoonotic diseases (Table 21-1).

Table 21-1

| Causative Organism | Small-Animal Host | Livestock Host | Wildlife Host | Mode of Transmission | |

| BACTERIAL INFECTION | |||||

| Anthrax | Bacillus anthracis | Dogs | Cattle, sheep, horses, goats | Most except primates | Contact |

| Brucellosis | Brucella melitensis | Dogs | Cattle, pigs, sheep, goats | All except primates | Contact, inhalation, ingestion |

| Campylobacteriosis | Campylobacter fetus | Dogs, cats | Cattle, poultry, sheep, pigs | Rodents, birds | Ingestion, contact |

| Capnocytophaga infection | Capnocytophaga canimorsus | Dogs, cats | Bite wound | ||

| Cat scratch disease | Bartonella henselae | Cats | Cats | Cat bite, scratch | |

| Erysipelas | Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | Pigs, sheep, cattle, horses, poultry | Rodents | Contact | |

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira spp. | All | All | Rats, raccoons | Contact with urine or birthing fluids |

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | Dogs, cats | Cattle, horses | Deer, birds, rodents | Tick bite |

| Pasteurellosis | Pasteurella multocida | Dogs, cats | Bite wound | ||

| Plague | Yersinia pestis | Cats | Rodents, rabbits | Flea bite | |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | Cattle, sheep, goats | Birds, rabbits, rodents | Inhalation, milk ingestion, contact | |

| Rat bite fever | Streptobacillus moniliformis | Rats | Rat bite | ||

| Salmonellosis | Salmonella spp. | All | All | Rodents, reptiles | Ingestion |

| Tetanus | Clostridium tetani | Horses | Reptiles | Wound | |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacteria tuberculosis | Dogs, cats | Cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, poultry | All except rodents and monkeys | Ingestion, inhalation |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | All | All except horses | Rodents, rabbits | Tick bite, contact with tissue |

| FUNGAL DISEASES | |||||

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcus neoformans | Birds | Contact | ||

| Ringworm | Trichophyton spp. | Dogs, cats | Cattle, horses, pigs, sheep | Rodents | Contact |

| PARASITIC INFECTION | |||||

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium parvum | Cattle | Ingestion | ||

| Hydatid disease | Echinococcus | Dogs | Herbivores | Wolves | Ingestion |

| Larva migrans | Toxocara, Ancylostoma, Strongyloides spp. | Dogs, cats | Pigs, cattle | Raccoons | Ingestion |

| Scabies | Sarcoptes scabiei | Dogs, cats, rodents | Horses | Primates | Contact |

| Schistosomiasis | Schistosoma | Dogs, cats | Pigs, cattle, horses | Rodents | Contact |

| Taeniasis cysticercosis | Taenia | Pigs, cattle | Boars | Ingestion | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | Cats | Pigs, sheep, goats | Ingestion | |

| Trichinosis | Trichinella spiralis | Pigs | Rats, bears, carnivores | Ingestion | |

| RICKETTSIAL DISEASES | |||||

| Psittacosis | Chlamydia psittaci | Psittacine birds | Ducks, turkeys | Birds | Inhalation |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | Dogs | Rodents, rabbits | Tick bite | |

| VIRAL DISEASES | |||||

| Contagious ecthyma (orf) | Poxvirus | Dogs | Sheep, goats | Contact | |

| Encephalitis (EEE, WEE) | Togavirus | Horses, poultry | Birds, rodents | Mosquito bite | |

| Hantavirus | Hantavirus | Rodents | Contact | ||

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis | Arenavirus | Mice | Varied | ||

| Monkeypox | Orthopoxvirus | Rodents | Contact | ||

| Newcastle disease | Paramyxovirus | Domestic birds | Poultry | Wild fowl | Contact, inhalation |

| Rabies | Rhabdovirus togavirus | Almost all | Most | Most | Animal bite |

| Simian herpes | Herpesvirus simiae | Primates | Animal bite, direct contact | ||

| Yellow fever | Togavirus | Primates | Mosquito bite | ||

| PROTOZOAL INFECTION | |||||

| Balantidiasis | Balantidium coli | Pigs | Rats, primates | Ingestion | |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium spp. | Most | Calves, sheep | Birds | Ingestion |

| Giardiasis | Giardia lamblia | Dogs, cats | Pigs, cattle | Beavers, zoo monkeys | Ingestion |

| Sarcocystosis | Sarcocystis | Dogs, cats | Pigs, cattle | Ingestion | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | Cats, rabbits, Guinea pigs | Pigs, sheep, cattle, horses | Cats | Ingestion |

EEE, Eastern equine encephalitis; WEE, Western equine encephalitis.

Veterinarians are ethically required to educate the public about zoonotic diseases. Because public health has been addressed in the American Veterinary Medicine Association (AVMA) Code of Ethics, many state boards and regulatory agencies have mandated such education, which can leave many veterinarians liable for a malpractice suit. To present a claim for malpractice, four elements must be proven: existence of a valid client-patient relationship, failure to practice the standard level of care, proximate cause, and harm that occurred to the patient as a result of substandard care. For more information on malpractice, see Chapter 4.

SAFETY HAZARDS IN THE VETERINARY PRACTICE

Wet Floors

When floors are being mopped, they can become extremely slippery. Signs that indicate a wet floor should be posted around the wet area, and team members should dry the wet area as soon as possible with a dry towel (Figure 21-1). Team members and clients should be encouraged to walk around the wet area. However, the sooner it is dry, the less likely it is that a slip or fall will occur. Team members are encouraged to wear nonskid shoes to help prevent slips in the veterinary practice.

Lifting

Team members must learn how to lift properly to prevent back injury (Figure 21-2). Lifting must always be done with the legs rather than the back; women are especially prone to use their backs. Team members should watch out for each other and guide others when lifting objects to ensure the back is kept straight and the legs are used to the maximum potential. It should be instituted that animals over 40 lb must be lifted by two team members to prevent back injuries.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT