Chapter 5 Observation

Symmetry and Posture

Forelimb Symmetry

Muscle Atrophy

The symmetry of skeletal muscle in the forearm, pectoral, and cervical areas should be assessed. Muscle atrophy that occurs in horses with chronic lameness conditions is called disuse atrophy and in those with neurological disease is called neurogenic atrophy. Horses with muscle atrophy and lower motor neuron disease (see Chapter 11) may be lame, sometimes as a result of muscle pain or nerve root pain, complicating differentiation between these causes of muscle atrophy. In most but not all horses with neurogenic atrophy, other clinical signs suggestive of neurological disease may be present. Horses with disuse atrophy resulting from chronic lameness usually have generalized atrophy of the ipsilateral forelimb. Muscle loss usually is not pronounced but involves the forearm (extensors are most commonly affected), triceps, and shoulder muscles. Shoulder muscle atrophy involving the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles generally is not pronounced, and lateral subluxation of the shoulder joint during weight bearing is not present (see Chapter 40).

Swelling

Cellulitis describes infection within the tissue planes of the distal extremities (see Chapter 14) and is sometimes called lymphangitis. Lymphangitis, by definition, is inflammation of the lymphatic circulation of the limb, but the conditions are similar and the terms are used interchangeably. Swelling is firm, warm, and painful, and lameness is often pronounced. “Stovepipe” swelling describes this condition (“the horse is all stoved-up”). Horses generally show systemic signs such as fever and elevated white blood cell count. Cellulitis usually results from small puncture wounds that may be difficult to discover or occurs after articular, periarticular, or subcutaneous injections. Infection develops in subcutaneous tissues or deeper in the dense fascial planes and can be difficult to eradicate.

Angular Deformity

Angular limb deformities in young horses are common, are sometimes associated with lameness or other developmental orthopedic disease, and are discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 58). Abnormalities of conformation should be noted but may have little relevance to the current lameness problem (see Chapter 4). Horses younger than 2 years of age with severe forelimb lameness of several months’ duration may develop contralateral varus deformity originating from the carpus or elbow joints.

Foot Size

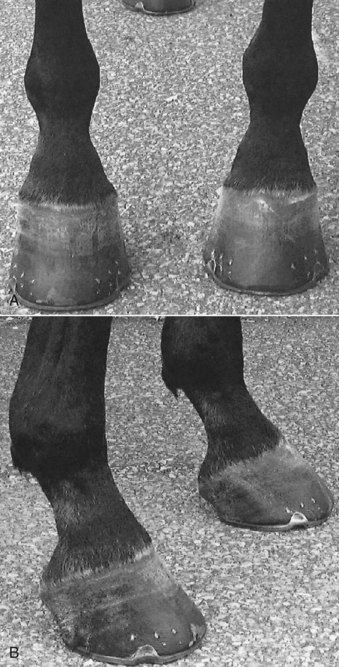

Ideally both front feet should be identical in size and shape, or nearly so, and any asymmetry should be noted. Horses with chronic lameness may have disparity in foot size, usually with the smaller foot being ipsilateral to lameness. The small foot often is contracted and more upright (Figure 5-1). Chronic reduction in weight bearing results in foot size disparity in some, but not all, horses. Mild disparity in foot size is a normal finding in some horses. Mild clubfoot conformation, acquired from previous flexural deformity, may be present incidentally in adult horses. Previous lameness may have caused contraction of the foot but has since resolved, resulting in disparity in foot size and shape but no residual lameness. In these horses it would be a mistake to assume current lameness is originating from the foot without confirmation using diagnostic analgesia. Clubfoot conformation appears to be better tolerated in Thoroughbred (TB) than in Standardbred (STB) racehorses.

Fetlock Height

Fetlock position should be assessed in the standing horse and during movement. In a standing horse, fetlock height should be symmetrical, assuming the horse is loading the limbs equally. Horses with severe lameness commonly “point” or hold the limb in front of the opposite forelimb, thus taking weight off the limb. This standing posture obviously causes disparity in fetlock height but should be carefully interpreted. Loss of support of a fetlock in the standing horse causes the affected fetlock to drop and occurs most commonly with acute, traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus in racehorses but also appears with chronic, active desmitis (Figure 5-2). Severe superficial digital flexor tendonitis or lacerations resulting in fiber damage of the deep or superficial digital flexor tendons can cause similar clinical signs.

In horses with mild flexural deformity of the metacarpophalangeal joint, dynamic knuckling (buckling forward, flexion) of the fetlock joint may occur in the standing position (Figure 5-3). Joint position usually returns to normal during movement. In horses with severe flexural deformity, normal fetlock position is never achieved. Knuckling of the fetlock also may result from desmitis of the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon.

Hindlimb Symmetry

Muscle Atrophy

Disuse and neurogenic muscle atrophy occur in the hindlimb. Horses with chronic hindlimb lameness develop ipsilateral gluteal muscle atrophy, but asymmetry may be subtle. Mild muscle atrophy usually first appears just lateral to a tuber sacrale. The veterinarian should differentiate muscle atrophy from disparity in height of the tubera sacrale (Figure 5-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree