CHAPTER 18 Nutritional Management of Diseases

Endocrinologic Diseases: Obesity,

Endocrinologic Diseases: Diabetes Mellitus,

Endocrinologic Diseases: Hyperthyroidism,

Musculoskeletal Diseases: Osteoarthritis,

Ophthalmologic Diseases: Herpesvirus Infection,

Pulmonary and Thoracic Medicine: Chylothorax,

Urinary Tract Disorders: Chronic Renal Disease,

Urinary Tract Disorders: Urolithiasis,

The American College of Veterinary Nutrition recommends a three-step approach to patient assessment that includes assessment of patient factors, dietary factors, and feeding factors. After the assessment phase, a nutritional treatment plan is developed and instituted, and serial monitoring and adjustment ensue (an iterative process).259 This chapter focuses on the nutritional management of feline disorders. Additional information on each disorder can be found in other chapters in this book.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular disease commonly occurs in cats with myocardial disease, occurring more commonly than valvular disease. The prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy has decreased after the discovery of its association with taurine deficiency213; hypertrophic and restrictive cardiomyopathies occur most frequently. Systemic arterial hypertension may also result in left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial failure. Cats with myocardial disease may be asymptomatic or may present with evidence of venous congestion, usually pleural effusion. For more information on cardiac disease, see Chapter 20.

Animal Factors

Cats with myocardial disease may be optimally conditioned or may be underconditioned or overconditioned depending on the severity and chronicity of the disease. Obesity results in blood volume expansion with elevated cardiac output, increased plasma and extracellular fluid volume, increased neurohumoral activation, reduced urinary sodium and water excretion, tachycardia, abnormal systolic and diastolic ventricular function, exercise intolerance, and systemic arterial hypertension.86 This may result in progression of the disease. Likewise, cachexia may occur with myocardial failure. Cachexia associated with heart disease or failure results in negative nitrogen and energy balance.89 The pathogenesis of cardiac cachexia is multifactorial, involving increased sympathetic tone, increased tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 levels, decreased physical activity with an increased resting energy requirement (RER), decreased tissue perfusion, venous congestion, and adverse effects of medications. Decreased nutrient intake and possibly increased nutrient losses (e.g., potassium loss with diuretic therapy) and loss of body weight and, more important, lean body mass occurs, resulting in an inability to respond to medical therapy and an increase in morbidity and mortality rates.

Cats have a dietary requirement for taurine because they have limited ability to synthesize it from cysteine and methionine and because it is used exclusively for bile acid conjugation. Taurine deficiency results in dilated cardiomyopathy in predisposed cats (Figure 18-1). The mechanism of heart failure in taurine-deficient cats is poorly understood. Taurine may function in osmoregulation, calcium modulation, and inactivation of free radicals.213 Other factors are likely involved because many cats fed taurine-deficient foods for prolonged periods fail to develop myocardial dysfunction. Additionally, there is an association between taurine and potassium balance.67 Inadequate potassium intake may induce significant taurine depletion, resulting in myocardial dysfunction. Male cats may be more prone to developing taurine deficiency–associated myocardial failure than are female cats, or male cats may be more prone to developing clinical signs at higher plasma taurine concentrations.83

FIGURE 18-1 Dilated cardiomyopathy in a 4-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat with taurine deficiency.

l-Carnitine is a conditionally essential nutrient involved with transport of long-chain fatty acids from the cytosol into the mitochondria, where they undergo beta oxidation for energy production. l-Carnitine deficiency has been associated with dilated cardiomyopathy in some dogs132; however, it has not been associated with this condition in cats.

Sodium intake is often restricted with heart disease; however, this may not be necessary until later in the course of the disease. Sodium restriction should occur concurrently with chloride restriction because chloride salt of sodium has more effect on blood pressure and plasma volume than non-chloride sodium salts.26 Salt sensitivity has not been documented to occur in cats. Hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are associated with arrhythmias, decreased myocardial contractility, and muscle weakness. Additionally, inadequate potassium intake may be associated with taurine deficiency.

Dietary Factors

Dietary recommendations for cats with cardiac disease are designed to optimize body condition and are summarized in Box 18-1. Commercial diets formulated for cats with cardiovascular disease are available.

BOX 18-1 Dietary Recommendations for Cats with Cardiac Disease

1 Restrict calories if obese; however, increase caloric intake if cachectic.

2 Protein content must be adequate or greater than normal (30% to 45% protein on a dry matter basis).

3 Omega-3 fatty acids may be beneficial in an omega-6 : omega-3 ratio of 5 : 1.

4 Sodium restriction (0.07% to 0.3% on a dry matter basis) with chloride restriction (to 1.5 times the sodium content) is indicated with congestive heart failure.

5 Adequate potassium (>0.5% on a dry matter basis), phosphorus (0.3% to 0.7% on a dry matter basis), magnesium (>0.04% on a dry matter basis). With diuretic therapy, additional potassium supplementation may be required to prevent hypokalemia.

6 Taurine should be present in the diet at >0.3% on a dry matter basis but can be supplemented at 250 to 500 mg by mouth every 12 to 24 hours.

Feeding Factors

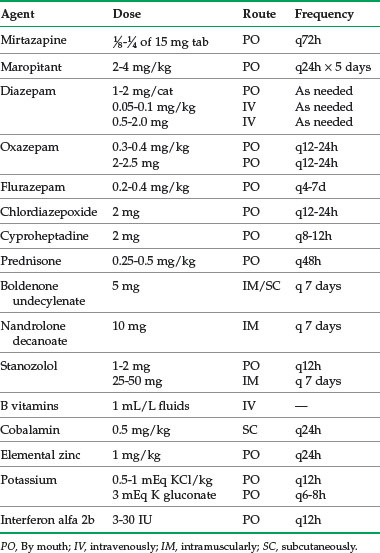

Some cats require feeding of frequent small meals because of decreased appetite. Pharmacologic appetite stimulation (Table 18-1) or assisted feeding through the use of feeding tubes may be required. Additional nutrients that may be beneficial include coenzyme Q10, which is required for energy reactions and is an antioxidant, and other antioxidants, which may decrease oxidative stress with dilated cardiomyopathy.

Dental And Oral Diseases

Primary oral diseases are subdivided into conditions affecting the tooth, periodontium, and other oral tissues. In many cases dental disease is secondary to a systemic condition such as chronic renal disease in cats, although primary disorders such as lymphoplasmacytic gingivitis–stomatitis, tooth resorption, and neoplasia occur in cats. For more information, see Chapter 21.

Dietary Factors

• Maintenance of tissue integrity

• Alteration of bacterial plaque metabolism

• Stimulation of salivary flow

• Cleaning of tooth and oral surfaces by physical contact

Claims of dry food being better for prevention of dental plaque than moist foods are unsubstantiated.30 Likewise, there are no data to support the notion that natural diets and foods are better for oral health than commercial foods. Dietary texture can be modified by increasing fiber content with a size and texture that promotes chewing and mechanical cleansing of teeth.30,161,272 Dental treats do not offer an advantage over dry foods; however, some contain hexametaphosphate, a calcium chelator, which may decrease calculus formation, although data are contradictory.114,256 Hexametaphosphate has not been evaluated in cats. Many oral diseases are inflammatory, and modification of the inflammatory process may be beneficial. Antioxidants, vitamins E and C, and selenium may be beneficial, but data are lacking in cats. Nutritional deficiencies of such elements as calcium and vitamins A, B, C, D, and E are associated with oral cavity disease, but these are uncommon (see Chapter 17).

Nutrition has been implicated as a cause of feline tooth resorption. Acid coating of foods has been suggested to cause tooth resorption, although this has not been proved.5,226,278 Dry food may cause microfractures that predispose teeth to infection and inflammation; however, this has not been proved. Dietary vitamin D has been implicated in tooth resorption. Evidence to support this assertion includes correlation between cats with tooth resorption and increased blood levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and histologic comparisons of the effects of excessive intake of vitamin D to the effects of bone resorption.226,227 Although a direct effect of vitamin D has not been established, there is evidence of an active vitamin D signaling in the pathophysiology of tooth resorption.27,28

Skin Disorders

The most common feline skin disorders are abscesses, parasitic dermatoses, allergy (flea bite hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis), miliary dermatitis, eosinophilic granuloma complex, fungal dermatitis, adverse reactions to food, psychogenic dermatoses, seborrheic conditions, neoplasia, and immune-mediated dermatoses.116,243

Animal Factors

Clinical signs associated with nutritional abnormalities include a sparse, dry, dull, and brittle hair coat that epilates easily; slow hair growth; abnormal scale accumulation; alopecia; erythema; crusting; decubital ulcers; and slow wound healing. Other clinical signs may be present with nutrient-deficient dermatoses (see Chapter 17). For more information on skin diseases, see Chapter 22.

Dietary Factors

Inadequate energy intake is associated with keratinization abnormalities, depigmentation, changes in epidermal and sebaceous glands, and increased susceptibility to trauma. Protein deficiency is associated with similar clinical signs. Essential omega-6 fatty acids include linoleic acid (>0.5% on a dry matter basis) and arachidonic acid (>0.02% on a dry matter basis).169 Omega-3 fatty acids can supply part of the omega-6 fatty acid component. Clinical signs of essential fatty acid deficiency include scaling, matting of hair, loss of skin elasticity, dry and dull hair coat, erythema, epidermal peeling, otitis externa, and slow hair growth. Certain mineral deficiencies may affect the skin (see Chapter 17). Copper deficiency is associated with loss of normal hair coloration, decreased density or lack of hair, and rough or dull hair coat. Many dermatologic conditions may occur with zinc deficiency and respond to zinc supplementation. Dietary phytate binds zinc, resulting in clinical signs of deficiency. Clinical signs of zinc deficiency include erythema, alopecia, and hyperkeratosis. Certain vitamin deficiencies may affect the skin. Vitamin A deficiency is associated with skin lesions and focal sloughing of skin. Vitamin E deficiency occurs in cats in association with steatitis. Clinical signs include erythema and keratinization defects. Vitamin E–responsive dermatoses include discoid lupus erythematosus, systemic lupus erythematosus, pemphigus erythematosus, sterile panniculitis, acanthosis nigricans, dermatomyositis, and ear margin vasculitis. Dermatologic conditions also arise from food allergies (see Chapter 17).

Feeding Factors

In cats with dermatologic disease, the veterinarian should evaluate the quality and quantity of the diet fed, including treats, snacks, and table food. A complete and balanced diet may be made incomplete or unbalanced when fed with other food stuffs. Homemade diets must be evaluated carefully.228 If a nutritional deficiency is suspected, the veterinarian should discuss with the owner the possibility of changing the diet to one of a higher quality. With suspected adverse food reaction, a diet change should be considered (see Chapter 17). If a specific nutrient deficiency is identified, the diet might be changed or supplemented accordingly. Zinc is supplemented for zinc-responsive dermatoses (zinc sulfate: 10 to 15 mg/kg per day by mouth; zinc methionine: 2 mg/kg per day by mouth). Vitamin A is supplemented for vitamin A–responsive dermatoses (tretinoin topically every 12 to 24 hours; isotretinoin: 1 to 3 mg/kg per day by mouth; etretinate: 0.75 to 1 mg/kg per day by mouth).

Fatty acid supplementation is often recommended for managing inflammatory skin disease. Cats have a limited capacity to convert 18-carbon long-chain fatty acids to 20-carbon long-chain fatty acids owing to low activity of delta-6-desaturase.201 It is 20-carbon long-chain fatty acids that are incorporated into cellular membranes and subsequently metabolized to prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes. To alter levels of these cytokines in cats, it is necessary to supplement 20-carbon long-chain fatty acids. Insertion of omega-3 fatty acid (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA]) into cell membranes results in production of cytokines of the odd-number series (e.g., prostaglandin E3, leukotriene B5) in place of the even-number series of cytokines produced from omega-6 long chain fatty acid, arachidonic acid (e.g., prostaglandin E2, leukotriene B4). These odd-numbered cytokines promote less inflammation and are more vasodilatory than the even-numbered cytokines. Cats being supplemented with omega-3 fatty acids must receive 20- and 22-carbon fatty acids owing to their limited ability to convert 18-carbon to 20-carbon fatty acids. The 20-carbon omega-3 fatty acid is EPA, and the 22-carbon omega-3 fatty acid is docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Oils derived from marine life are high in EPA and DHA. Oils derived from plant life, such as flax seed and borage, contain primarily 18-carbon fatty acids, therefore limiting their conversion to the required 20-carbon fatty acid and their effectiveness in managing inflammation. There are no data on the effectiveness of omega-3 fatty acids in managing inflammatory skin diseases in cats.41

Gastrointestinal Diseases

Many disorders of the gastrointestinal system may respond to dietary management, whether or not the disorder is due to diet. For more information on gastrointestinal diseases, see Chapter 23. For information on adverse reactions to food, see Chapter 17.

Types of Foods Used in Managing Gastrointestinal Disease

Dietary Factors

Several options exist for nutritional management of cats with inflammatory gastroenteritis.106,280 In addition to pharmacologic therapy, cats may respond to elimination diets, whether it is a diet containing a novel protein source, a protein hydrolysate diet, or a homemade simple-ingredient diet. Inflammatory reactions are thought to occur through interaction of a protein with an antibody directed against it. Novel protein refers to a single dietary protein source that the cat has not been fed before; therefore an inflammatory response would not be evoked.106 A protein hydrolysate diet involves feeding a diet where the protein has been hydrolyzed to a size that is not recognized by antigen processing cells and antibodies, typically below 12,000 daltons.43 A homemade diet often comprises single unprocessed ingredients. In processing of foods, glycated protein end-products may be produced through the Mallard reaction and these glycated end-products may induce an inflammatory response. Feeding unprocessed foods decreases exposure to these glycation end products and subsequent inflammatory response.156

Cats with large intestinal disease may respond to an elimination diet or to a higher fiber (>5% on a dry matter basis) diet.63,202,247,280 Dietary fiber increases fecal bulk, which stimulates colonic contraction; however, it increases fecal volume, which could exacerbate constipation.247 Dietary recommendations for cats with inflammatory bowel disease are summarized in Box 18-2.61

BOX 18-2 Dietary Recommendations for Cats with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

1 Fat: 15% to 25% when feeding a highly digestible diet or 9% to 18% on a dry matter basis when feeding a fiber-enhanced diet.

2 Protein: >35% on a dry matter basis. When using a limited protein (elimination) diet, restrict protein to one or two sources and use a protein source that the cat has not consumed previously (novel protein).

3 Fiber: <5% on a dry matter basis for highly digestible diet or 7% to 15% for foods with increased fiber.

4 Digestibility: >87% for protein and >90% for fat and digestible carbohydrate for highly digestible diet, or >80% for protein and fat and >90% for carbohydrate for high fiber diet.

Hepatic Disease

The liver is a metabolically active organ involved with digestion and nutrient metabolism, synthesis (e.g. albumin), storage (e.g., glycogen), removal of environmental and endogenous noxious substances, and metabolism of drugs and toxins. The liver influences nutritional status through bile acid synthesis and excretion into the gastrointestinal tract and its central role in intermediary metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates, fat, and vitamins. The most common causes of feline liver disease include inflammatory conditions (cholangitis–cholangiohepatitis complex), lipidosis, neoplasia (particularly lymphoma), and portovascular anomalies.194 For more information on liver diseases, see Chapter 23. Nutritional management of hepatobiliary disease is usually directed at clinical manifestations of the disease rather than the specific cause. Goals of nutritional management of cats with liver disease include the following:

• Maintaining normal metabolic processes and homeostasis

• Avoiding and managing hepatoencephalopathy

• Providing substrates to support hepatocellular repair and regeneration

• Decreasing further oxidative damage to damaged hepatic tissue

Dietary Factors

Maintenance of body condition and weight is important; therefore adequate caloric intake is paramount. Hepatic lipidosis is a result of negative energy balance with mobilization of peripheral adipose tissue and accumulation of intrahepatic lipid.46 In managing cats with hepatic lipidosis, reversing the negative energy balance is most important in reversing the disease process. Protein restriction is not necessary unless hepatoencephalopathy and hyperammonemia are present. Hypokalemia may occur with liver disease and has been reported in approximately one third of cats with hepatic lipidosis46; therefore diet should be potassium replete. Many hepatic diseases are associated with oxidative stress that may induce further hepatocellular damage. Feeding diets with additional antioxidants or supplementing with antioxidants may be beneficial. Hepatic dysfunction entails a dysregulation of lipid metabolism; this is particularly prominent with hepatic lipidosis. l-Carnitine is involved with lipid metabolism, and although l-carnitine deficiency does not occur with hepatic lipidosis,126 l-carnitine supplementation at 250 to 500 mg daily may be beneficial in cats with hepatic lipidosis.44

Dietary recommendations for cats with hepatobiliary disease are summarized in Box 18-3.194

BOX 18-3 Dietary Recommendations for Cats with Hepatobiliary Disease

1 An energy-dense diet containing >4.2 kcal/g

2 Protein: 30% to 45% on a dry matter basis unless hepatoencephalopathy is present: 25% to 30% on a dry matter basis

3 Arginine: 1.5% to 2% on a dry matter basis

4 Taurine: >0.3% on a dry matter basis

5 Potassium: 0.8% to 1.0% on a dry matter basis

6 L-carnitine: >0.02% on a dry matter basis

Endocrinologic Diseases: Obesity

Obesity is the most important nutritional disease of cats. With prevalence rate estimates of up to 40%,8,166,242 obesity must be considered a significant hazard to cats. Increased emphasis on pet health and preventive health programs makes obesity prevention an important aspect of health maintenance programs in dogs and cats. Treatment for obesity varies from frustrating to rewarding, and evaluating and prescribing for successful, long-term weight loss and maintenance usually require management of multiple, interrelated patient and client factors. Diagnosis of disease secondary to obesity and the major task of client education and motivation are the province of the veterinarian.

Obesity is a condition of positive energy balance and excess adipose tissue accumulation that adversely affects the quality and quantity of life. Obesity literally means increased body fatness, but measurement of fat fractions of body composition is difficult in practice. Therefore obesity can be defined as body weight in excess of 15% to 20% of ideal, owing to the accumulation of body fat.281 Negative health manifestations often begin at this level of weight excess and are a virtual certainty at a 30% excess over ideal weight. Associated health risks include musculoskeletal and cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hepatic lipidosis, higher incidence of cancer, possible anesthetic and surgical complications, decreased heat tolerance and stamina, and reproductive problems. Obesity is a proinflammatory condition, and adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ that produces cytokines called adipokines.168,221 This may explain in part the association of obesity with inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis.

The pathogenesis of obesity is multifactorial and is more than just “too much energy in and not enough energy out.”145 There are genetic, gender, and environmental influences. Apartment dwelling, inactivity, middle age, being male, neutered status, mixed parentage, and certain dietary factors are associated with being overweight.166,242 The pet owner’s contribution to the problem may be significant and must be understood and addressed. In one survey of more than 18,000 dog and cat owners in Australia and the United States, almost a third of owners reported their pets as overweight or obese, but fewer than 1% felt that obesity was a health problem.87 In another study of 120 German owners of indoor cats, questionnaire responses of owners of cats with normal body weight were compared with responses from owners of overweight cats.133 Owners of overweight cats were more likely to watch their cats eat and relented more frequently when their cats begged for food. Owners of overweight cats were less likely to spend time playing with their cats and appeared to have a different relationship with them, being more likely to anthropomorphize them and consider them a substitute for human companionship.

Diagnosis of obesity is the first step in managing the disease. Determining whether a cat is overweight is not difficult; however, accurately determining the degree of overweight and the cat’s ideal weight is challenging. Many owners underestimate their cat’s body condition, and veterinarians may overlook obesity. Documenting body weight in the medical record is important; in fact, veterinarians may be part of the problem. In one study medical records dramatically underreported overweight and obesity in cats when body condition scoring (BCS) results were compared to reported diagnoses.166 For example, the prevalence of obesity defined by BCS in the population studied was 6.4% compared with 2.2% when defined by a recorded diagnostic code in the medical record. In addition to recording the body weight, it may be helpful to calculate the percentage change in weight since the last visit and compare it to a similar weight gain in a person. For example, an 8.8-lb (4-kg) cat that has gained 1 lb (0.5 kg) has increased its body weight by approximately 12%; this is equivalent to a 14-lb weight gain for a 120-lb person.

Muscle condition scoring and BCS provide additional information regarding the appropriateness of the cat’s body weight to its overall condition.* Several BCS systems are available; the most widely used are the 5-point and 9-point scales (see Table 16-2).† In both scales the middle value (3/5 or 5/9) is considered optimal condition, and these cats have 15% to 25% body fat. Lower values on the scale are degrees of undercondition (cats having 2/5 or 3/9 have 5% to 15% body fat, and cats having 1/5 or 1/9 have <5% body fat), whereas higher values on the scale are degrees of overcondition (cats having 4/5 or 7/9 have 25% to 35% body fat, and cats having 5/5 or 9/9 have higher than 35% body fat).265 As additional data are generated, it is likely that revisions of the scales will occur.265 Muscle condition scoring assesses muscle mass and tone.196 Evaluation of muscle mass includes visual examination and palpation over the temporal bones, scapulae, lumbar vertebrae, and pelvic bones. Decreased muscle mass may increase morbidity and mortality rates associated with disease.52

Animal Factors

The most important step is to recognize that a cat is overweight or obese. The veterinarian should compare the BCS with body weight, especially with historical data from annual examinations. Often a cat’s ideal body weight can be determined by finding its weight at about 1 year of age in the medical record. Cats that are obese may show clinical signs of related conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hepatic lipidosis, and osteoarthritis. The veterinarian should take a good dietary history, including the type(s) of food fed, amount(s), and frequency.195 It is important to gather information about snacks, treats, and table foods that may be fed, as well as access to food in the outdoors if the cat is allowed access (Box 18-4). It may be helpful to have the owner keep a food diary for 1 or 2 weeks before the weight loss program is initiated. Collecting the information may help make owners aware of the role they play in the cat’s obesity, as well as provide useful information.

Dietary Factors

Feeding Factors

Weight-reduction programs are a multistep approach involving owner commitment, a feeding plan, and repeated communications and monitoring.145,281 Owners must recognize that their cat is obese and understand associated health risks. Before instituting a weight loss program, the veterinarian should perform a thorough physical examination and obtain a minimum database (complete blood count, chemistry panel, urinalysis) to detect concurrent diseases. Then a feeding plan should be instituted. The veterinarian should first set the amount of calories to be fed on the basis of known or estimated energy requirements (see Chapter 15). Calculate the RER:

or

This number is multiplied by a factor of 0.8 to induce a weight loss of 1% to 2% body weight per week. The veterinarian should compare this estimated energy requirement with current caloric intake because some animals require further restriction to induce weight loss.268 The calculations for an 8-kg cat with an ideal body weight of 5 kg would be as follows:

Achieving a safe weight loss of 3 kg will take 5 to 9 months.

The veterinarian should choose a commercial diet, as previously described, and recommend that it be fed to meet the energy requirements estimated to induce weight loss. The veterinarian should eliminate or account for additional food and treats in the caloric intake, which should be less than 5% of total daily caloric intake. Some animals tolerate an abrupt change in diet with little problem, although some appear to have fewer gastrointestinal issues if food is gradually changed over a 7- to 10-day period. A new diet may be readily accepted by some cats, but patience will be required with others (Box 18-5).

BOX 18-5 How to Change a Cat’s Diet

1 Meal feeding may make the transition to a new diet easier than ad libitum feeding because the cat is more likely to be hungry at mealtime. The transition to meal feeding can be made by leaving food out for 1 hour two to three times per day. It is often easiest to start this during the time of day when the owner is normally away from home and cannot be tempted to feed the cat off schedule.

2 Offer the new food along with the old food, rather than abruptly discontinuing the old food. Ideally, both foods should be in the same type of familiar bowl. It may be necessary to offer the new food for several days to a week or even longer before the cat will try it. Once the cat starts consuming the new food, decrease the amount of the old food offered by a small amount each day, with the aim of transitioning totally to the new diet over a 1- to 2-week period.

3 Another method of introducing a new diet involves mixing the old and new foods together. For the first few days, the cat is offered a mix of 75% current food and 25% new food. Then the ratio is changed to 50 : 50 for the next few days. By the end of the first week, it may be possible to offer 25% current diet and 75% new diet. The amount of the new food is increased thereafter until the cat is consuming 100% of the intended diet.

4 Cats must be exposed to both the smell and the taste of a new food to overcome neophobia. If the new diet is a canned food, it may be helpful to smear a small amount on a front paw to encourage the cat to lick and taste the food.

5 Enhancing the smell and flavor of the new food can be accomplished by warming it slightly or adding small quantities (approximately 1 tablespoon) of tuna or clam juice or low-salt chicken broth.

The goal of weight reduction is to reduce the cat’s excess adipose tissue; however, loss of lean muscle mass occurs as well.98 Feeding a high-protein diet is associated with less lean muscle loss.267 Additionally, increased dietary fiber is associated with decreased protein digestibility75; therefore high-fiber diets are formulated to account for this. It is important that owners ensure that the obese cat continues to eat because of the risk of hepatic lipidosis. l-Carnitine (250 to 500 mg/day, by mouth) has been shown to be beneficial in preventing hepatic lipidosis with weight loss in obese cats.24,48 Diets should contain more than 500 ppm.

Although meal feeding is associated with more consistent weight loss, this may not be possible depending on the cat. Providing a measured amount of food during a 24-hour period achieves the same goal. Using food puzzles or hiding food in various locations both provides a more stimulating environment and encourages energy expenditure (Figures 18-2 and 18-3). When feeding dry diets, some owners find using pre-weighed portions of food more acceptable than measuring the amount of food daily in a cup.23 In multicat households the owner should strive to keep the obese cat from eating food provided for nonobese cats. This can be accomplished by separating the cats and limiting the time for meal consumption. Another strategy is to provide food for the nonobese cats in an area that the obese cat cannot enter (e.g., a box with a hole that only the nonobese cats can fit through). Many owners have become accustomed to using food and treats to enhance the bond with their cat and mistakenly believe that eating is a social event for cats, as it is for humans. In addition, owners often mistake any vocalization as a cry for food. Teaching owners to interact with their cats through play or training sessions may be an important part of the program. Environmental enrichment for indoor cats can be an integral part of a weight loss program.

FIGURE 18-2 Food puzzle to encourage energy expenditure by a cat to acquire food.

(Courtesy Steve Dale.)

Prevention of obesity is easier than treating obesity in cats. The veterinarian should teach owners how to keep their cat’s body condition from lean to optimally conditioned during growth.9,19,111,120,182 It will be necessary to adjust food intake after neutering because gonadectomy reduces energy requirements, although food intake increases within weeks of surgery. At every veterinary visit, a cat’s body weight and BCS should be recorded in the medical record.111,129,233

Endocrinologic Diseases: Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is the most common endocrine disease in cats. It may be insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), in which absolute insulin deficiency occurs, or non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), in which insulin antagonism occurs; between 50% and 70% of cats with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus have NIDDM. The goals of managing a cat with diabetes mellitus include achieving and maintaining optimal body condition and maintaining euglycemia. Obese cats with NIDDM may become nondiabetic with weight loss and dietary management.20,85,135,231 For more information on diabetes mellitus, see Chapter 24.

Animal Factors

Insulin is a major anabolic hormone involved with energy, protein, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism. With insulin deficiency or insulin antagonism, anabolic metabolic pathways are disrupted, resulting in polyuria/polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss, muscle mass loss, decreased body condition, and clinical signs of ketoacidosis with progression of IDDM (e.g., vomiting, anorexia, seizures). Cats with NIDDM are typically obese and do not generally develop ketoacidosis. Risk factors identified for NIDDM in cats include indoor confinement and decreased physical activity, likely resulting in obesity and insulin resistance; type of food consumed is not necessarily a risk.223,248

Dietary Factors

Dietary management of cats with diabetes mellitus depends in part on whether IDDM or NIDDM is present. For cats with IDDM, timing of meals with insulin administration is advantageous; however, some cats with diabetes mellitus eat small meals even when fed ad libitum.180 Diets that are higher in fiber may increase insulin sensitivity and blunt postprandial hyperglycemia.135,203 In cats that are underconditioned as a result of unregulated IDDM, feeding a calorically dense diet to increase body weight and condition may be necessary while regulating the IDDM with insulin.

Because cats with NIDDM are typically obese, weight loss is an important component of management. Many cats can go into diabetic remission with a combination of weight loss and insulin treatment178 or weight loss alone. Traditional diabetic cat diets have been fortified with fiber to reduce postprandial glucose absorption and control weight.135,203 Many cats respond to being fed low-carbohydrate, high-protein diets. In studies so far, low-carbohydrate, high-protein diets are associated with improved remission rates compared with higher-fiber diets (68% versus 41%) and maintain more lean body mass during weight loss.* However, in cats that do not go into remission and require long-term therapy, there appears to be little difference between the diets. In addition, some cats respond better to high-fiber diets, and weight control may be easier with a less calorically dense food. Canned food is preferred in diabetic cats to maintain hydration, lower carbohydrate content, and improve satiety. Dietary recommendations for cats with diabetes mellitus are summarized in Box 18-6.279

BOX 18-6 Dietary Recommendations for Cats with Diabetes Mellitus

• Carnitine (250 to 500 mg per day, orally) is important for the breakdown of long-chain fatty acids. By facilitating energy utilization of fats, carnitine protects against muscle catabolism during weight loss. Carnitine has also been shown to suppress ketogenesis and acidosis in starving dogs and protect liver function in fasting cats.24,48,124

• Chromium is thought to increase insulin receptor numbers and activity. There are no studies in cats with diabetes, only in healthy cats.6

• Vanadium is thought to have insulin-like activity. One study showed vanadium lowered fructosamine, insulin requirements, and clinical signs in diabetic cats; however, vomiting and anorexia were significant side effects.179

• The role of taurine in diabetes is still controversial. Taurine is thought to exert antioxidant and antiinflammatory properties that decrease the incidence of diabetic complications such as neuropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular disease. Little research has evaluated taurine for use in diabetic cats.

• Supplementation with omega fatty acids in human studies has shown improved lipid metabolism and increased glycolysis in cells; however, they have not been evaluated in cats with diabetes mellitus.

Endocrinologic Diseases: Hyperthyroidism

Animal Factors

Hyperthyroidism is a clinical condition associated with excessive production and secretion of thyroxine (T4). Most cats are older, with an average age at diagnosis of 13 years. Clinical signs associated with hyperthyroidism are usually polyphagia with weight loss, loss of muscle mass, polyuria/polydipsia, and hyperactivity; hyperthyroidism is also associated with cardiomyopathy. Because hyperthyroidism occurs in older cats, it may be associated with other diseases, most commonly chronic kidney insufficiency, which may become unmasked when the hyperthyroidism is treated. For more information on hyperthyroidism, see Chapter 24.

Dietary Factors

Most cats with hyperthyroidism are underweight and underconditioned; therefore feeding a calorically dense diet may be helpful in restoring body condition and weight. Increasing the fat content of the diet increases the caloric content. Underweight cats should receive a diet containing higher levels of protein; however, caution is necessary because of the association of renal disease with hyperthyroidism. Concentrations of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine should be monitored. If renal azotemia develops with treatment of hyperthyroidism, then dietary protein should be restricted (see the section on renal disease). Nutritional recommendations for feeding underweight cats with hyperthyroidism are summarized in Box 18-7.279

BOX 18-7 Dietary Recommendations for Feeding Underweight Cats with Hyperthyroidism

Nutritional factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of hyperthyroidism, although the etiopathogenesis is not known. Epidemiologic studies have identified consumption of commercial canned foods, especially fish or liver and giblets, as a risk for development of hyperthyroidism, which suggests that a goitrogenic compound may be present in the diet.130,181,207,270 However, no specific goitrogenic factor has been identified. Iodine is one potential dietary goitrogen; however, most commercially prepared cat foods contain adequate amounts of iodine. It is important to note that such studies show association but not necessarily a cause-and-effect relationship. Additional non-nutritional risk factors have been identified, including use of cat litter; being an indoor cat; sleeping on the floor; presence of dental disease; presence of a smoker in the house; use of flea products; and exposure to herbicides, pesticides, or plant pesticides.130,181,207,270

Musculoskeletal Diseases: Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) has multiple etiologies and is characterized by pathologic changes of synovial or diarthrodial joints that are accompanied by pain and disability. Although the prevalence of OA in cats is unknown, radiographic evidence was found in 63 of 292 cats (22%) in one study.101 Clinical signs of OA in cats include decreased activity, reluctance to jump or climb stairs, decreased grooming, lameness, inappropriate elimination, decreased appetite, and lethargy.18 For more information on osteoarthritis, see Chapter 26.

Animal Factors

OA occurs more commonly in cats older than 10 years of age. In one study of cats older than 12 years that were examined for reasons other than lameness, 90% of radiographs taken demonstrated OA.109 Overweight cats are approximately 3 times more likely to present for lameness not associated with cat bite abscess.241 Obesity may cause excessive forces on joints and articular cartilage, resulting in inactivity and further weight gain; however, obesity is a proinflammatory condition.38,69,105,282 Therefore obesity may result not only in abnormal mechanical forces on joints but also in production of adipokines, and upregulation of inflammatory pathways associated with obesity may promote joint inflammation and progression of OA.222

Dietary Factors

There is a paucity of information concerning nutritional management of OA in cats. Weight loss is an important component of nutritionally managing OA in cats (see the section on obesity). In one study consumption of a diet containing high levels of n3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid) and supplemented with green-lipped mussel extract and glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate improved activity in cats with OA.149 There are no studies evaluating supplementation with n3 fatty acids, glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate, antioxidants, or nutraceuticals in cats with OA. As mentioned, n3 fatty acids may alter inflammation through production of odd-numbered cytokines.15,38,246 Antioxidants scavenge free radicals that are increased with OA and may be beneficial.17,38 Chondromodulating agents such as chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine may slow progression or alter processes involved with OA, including stimulating cartilage matrix synthesis, inhibiting catabolic enzymes, and increasing fluidity of synovial fluid.17,38

Oncology

Cancer is among the most common causes of non-accidental death in cats. Nutritional management of cats with cancer has several goals. Nutritional support can reduce or prevent toxicosis associated with cancer therapy (medical, surgical, radiation, or combination) and ameliorate presumed alterations in metabolism associated with cancer; possibly, specific nutrients can be used to treat cancer directly or indirectly.240 There are four stages of metabolic alterations that may occur with cancer:

1 Phase 1 is a preclinical phase with no obvious clinical signs; metabolic changes include hyperlactatemia, hyperinsulinemia, and altered amino acid profiles.

2 Phase 2 is associated with early clinical signs, such as anorexia, lethargy, and weight loss; metabolic changes are similar to those of phase 1.

3 Phase 3 is associated with advanced clinical signs, such as cachexia, anorexia, lethargy, and increased morbidity associated with cancer treatment; metabolic changes are more profound than in phases 1 and 2.

4 Phase 4 is recovery and remission; metabolic changes usually persist.240

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree