Dyspnoea

Crackles on auscultation

Open mouth breathing

Cough*

Muffled lung sounds

Pale or cyanotic mucous membranes

Tachycardia

Bradycardia

Irregular rhythm and pulse deficits

Gallop rhythm†

Murmurs‡

Weak pulses

Jugular distension and pulsation

Slow CRT

Weakness

Syncope

Collapse

Hepatomegaly

CRT, capillary refill time.

* Coughing is uncommon in cats with cardiovascular disease.

† Gallop rhythms are more common in cats.

‡ Murmurs are more common in dogs.

When examining the cardiovascular system it is important to differentiate between hypovolaemic and cardiogenic shock (see Chapter 3), as the stabilisation of each is distinctly different. The clinical history should help, but close attention should be paid on physical examination. Both syndromes could produce pale mucous membranes, cold extremities, weak pulses and reduced arterial blood pressure. The presence of murmurs, arrhythmias, pulmonary oedema, pulse deficits or irregular pulses would increase the suspicion of cardiac disease.

Initial Stabilisation of the Cardiac Patient

- A low dose test bolus of crystalloids can be infused to determine if hypotension is volume related. An increase in blood pressure with decrease in heart rate, in response to fluid bolus, implies hypovolaemia.

- Hypotension not responsive to fluid infusion implies low output cardiogenic causes.

- Ideally, central venous pressure monitoring should be performed on patients with cardiac disease receiving large volumes of intravenous fluids, e.g. for treatment of hypovolaemia (see Figure 10.3).

Figure 10.1 Application of nitroglycerin ointment to the pinna of a dog with congestive heart failure.

Assessment

Arterial Blood Pressure

Measuring arterial blood pressure is useful in assessing cardiovascular function. Indirect methods of measuring blood pressure are most convenient (e.g. Doppler sphygmomanometer) but rely on the detection of a distal pulse, so in hypotensive patients this may not be possible. Direct measurement of arterial blood pressure via an arterial catheter can provide continuous monitoring and assess response to treatment; this is the ‘gold standard’ method of arterial blood pressure measurement.

Hypotension is usually taken to mean a systolic pressure below 90 mmHg, and a mean arterial pressure (MAP) below 65 mmHg. A MAP of 70–80 mmHg is necessary to provide perfusion of vital organs (see Figure 10.4).

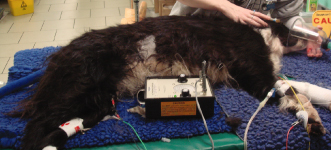

Figure 10.4 Blood pressure measurement and electrocardiogram (ECG) carried out on a critical patient.

Arterial Blood Gases

Arterial blood gas analysis (see Chapter 6) is useful in assessing the impact of congestive heart failure (CHF) on respiration. Hypoxaemia and hyperventilation are typically seen where pulmonary oedema is compromising respiration.

Radiography

Thoracic radiography can provide useful information regarding heart size and shape, the presence of pulmonary oedema and pleural effusions. However, the stress of restraining and positioning an animal for radiographic studies should not be underestimated, and anaesthesia is contraindicated because of the cardiosuppressive effects of most anaesthetic agents. In the initial assessment of the cardiac patient, pulmonary oedema and pleural effusion can usually be diagnosed and treated appropriately based on history and examination alone (see Figure 10.5).

Radiographs can be taken once the animal has been stabilised:

- Cardiomegaly is common in canine patients with CHF. The individual chambers should be assed for enlargement and the whole heart silhouette can be assessed using the vertebral heart score.

- A large globe-shaped cardiac outline may indicate pericardial effusion.

- Pulmonary parenchyma should be assessed for evidence of pulmonary oedema. This may cause a diffuse interstitial pattern initially and progress to an alveolar pattern with air bronchograms. Dogs with CHF commonly have pulmonary oedema and the peri-hilar region is the most common site.

- Pulmonary vascular patterns can be assessed on dorsoventral (DV) and lateral views, with pulmonary venous distension being indicative of cardiac disease.

- Pleural effusions are readily diagnosed on lateral and DV views.

Electrocardiography

An electrocardiogram (ECG) provides valuable information on rate and rhythm and is essential to assess arrhythmias. Arrhythmias are clinically important; they may cause or exacerbate low cardiac output states. It may be impossible to resolve congestive heart failure signs without controlling concurrent arrhythmias. Arrhythmias can contribute to myocardial ischaemia.

The ECG is the ‘gold standard’ for identification of an arrhythmia. It should be remembered that the ECG is not sensitive in detecting cardiac chamber enlargement (echocardiography and radiography are much more sensitive). An ECG provides no information about the ability of myocardium to contract, nor does it provide any information about the heart valves or endocardium. The ECG is the only way to diagnose the actual arrhythmia and hence provide appropriate treatment for the patient.

Cardiac arrhythmias can contribute to morbidity and mortality in critically ill dogs and cats. Successful management of arrhythmias often involves investigation and correction of an underlying non-cardiac disorder, and management of contributing factors in cases with severe systemic illness. In animals with primary cardiac disease, arrhythmia management is usually accomplished with drug therapy or cardiac pacing.

Echocardiography (Ultrasound Examination)

Ultrasound examination is the most effective method of assessing heart chamber enlargement, valve regurgitation and myocardial contractility. Other uses are to confirm pericardial or pleural effusions and assist in ultrasound-guided drainage (see Figure 10.6).

Common Emergency Presentations

Congestive Heart Failure

Congestive heart failure occurs as a result of chronic cardiac insufficiency and the body’s own attempts to compensate for this insufficiency. If the left ventricle begins to fail, pulmonary oedema occurs (peripheral venous congestion); if the right ventricle begins to fail then systemic venous congestion is seen, resulting in ascites, hepatic congestion and, occasionally, peripheral oedema.

Why the heart should fail can be due to a number of causes (see Table 10.2). Patients may have had a history of CHF and may be on treatment already, or this may be the first time a cardiorespiratory problem has been noticed by the owner. Patients are usually dyspnoeic at presentation and require immediate stabilisation before further investigations can be carried out.

Table 10.2 Causes and examples of cardiac failure

| Cause of failure | Effect on cardiovascular system | Examples |

| Systolic failure | Poor contraction of the myocardium results in poor ‘pumping’ of blood | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| Diastolic failure | Prevention of the ventricle from fully relaxing and filling during diastole | Restrictive cardiomyopathy Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Pericardial effusion |

| Valvular disease | Pathology of the valves of the heart leads to reduced efficiency | Endocardiosis Valvular dysplasia Endocarditis |

| Rhythm disturbances | Poor coordination of the contraction of atria and ventricles leads to reduced output | Tachydysrhythmias Bradydysrhythmias |

Canine patients with myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) are commonly affected. Cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) are also frequently presented.

Patients often present with a history of collapse and breathing difficulties, with or without a cough. On examination they have pale or cyanosed mucous membranes, marked abdominal respiratory effort, expiratory pulmonary crackles suggestive of oedema, ventral dullness on auscultation of the chest suggestive of pleural effusion, rapid respiratory rates and anxiety.

The diagnosis will be made based on the history and clinical examination; radiography and echocardiography should always be reserved until the patient is stable.

The most significant problem for these patients is the marked pulmonary oedema, or in the case of cats more frequently pleural effusion. The patients should receive oxygen supplementation and the following medications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree