CHAPTER 54 Novel Anticonvulsant Therapies

A seizure is the clinical manifestation of hypersynchronous abnormal neuronal activity originating in the cerebral cortex. Seizure disorders are a well recognized neurological problem in cats.1–5 Much of what is known regarding the etiology and diagnosis of feline seizure disorders can be extrapolated from dogs; however, caution should be taken when comparing treatment options between the two species.

There are various classification schemes for seizure disorders and types. One scheme classifies seizure disorders as primary and secondary. Seizure types can be classified as focal or generalized.1,5 Focal seizures originate from a discrete epileptogenic focus within the cerebral cortex. Clinical features of focal seizures in cats are variable, including drooling, facial movements, hippus, excessive vocalization/growling, random skittish behavior, and abnormal head, neck, or limb movements.1,6 Focal seizures can progress into generalized seizures, although they occur more commonly as isolated episodes. Generalized seizures originate from both cerebral hemispheres and usually manifest as tonic-clonic movements. These may be particularly violent in cats, and often are accompanied by salivation, urination, defecation, and pupillary dilation.6

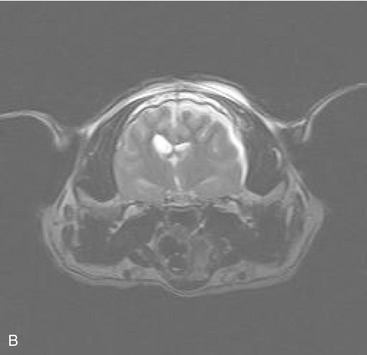

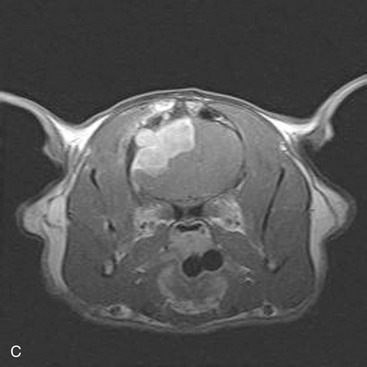

Primary seizure disorders are those conditions that have no underlying cause. Cats who are determined to have a primary seizure disorder are diagnosed as idiopathic epileptics. Typically these seizures are generalized; however, focal seizures also may be a feature of idiopathic epilepsy. Historically, focal seizures have been associated with structural lesions of the forebrain; however, in the authors’ experiences the presence of focal seizures does not exclude a diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy. Secondary seizure disorders are classified as conditions in which an underlying structural lesion, such as neoplasia, trauma, hydrocephalus, infection, ischemia, or metabolic disease has been identified (Figure 54-1). Differentiating between the two classification schemes of seizure disorders is critical for determining a prognosis, as well as for devising an appropriate treatment plan. In both situations, anticonvulsants are needed to treat the seizure activity; additional therapies may be necessary for treating secondary seizure disorders.

PRINCIPLES OF ANTICONVULSANT THERAPY

Initial seizures are associated with either a single or a limited number of epileptic foci within the cerebral hemisphere. The number of cells with the ability to fire spontaneously (a focus of pacemaker cells) increases with progressive seizure activity. A similar focus also may develop in the same location in the opposite hemisphere with continuous or recurrent seizure activity causing the number of foci to multiply rapidly. Therefore an increase in the number or severity of seizures is accompanied by an increase in neurons that fire spontaneously and propagate seizure activity.7 The severity of seizures in cats is not a good prognostic indicator; this is in contrast to response to therapy.3 Aggressive, safe, and effective anticonvulsant therapy is critical for achieving a therapeutic response.

The major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain is gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and the major excitatory neurotransmitter is glutamate. Imbalance between these neurotransmitters can lead to seizure activity. Additionally, within an epileptic focus there are periods of exaggerated depolarization known as a paroxysmal depolarization shift (PDS).7 The PDS originates in the dendritic zone of the neuron. Both influx of calcium through voltage-gated calcium channels and influx of sodium through non-NMDA and NMDA receptor channels are theorized to give rise to the PDS. Channelopathies or mutations within the ion channels can be responsible for the generation of seizures. Following brain and/or neuronal injury, changes occur in the inherent excitability of glutaminergic neurons. These voltage-gated calcium channels become abnormally sensitive, and there is morphological and functional loss of the inhibitory neurons and synapses such as GABA.

Knowledge of the pathogenesis of seizures allows for a better understanding of the general mechanism of action of anticonvulsants. Anticonvulsant drugs often are characterized based on their anticonvulsant activity against single seizures induced by maximal electrical or chemical stimulation in experimental animal models that use a maximal electroshock seizure and the pentylenetetrazol seizure tests. Most conventional antiepileptic drugs have anticonvulsant activity in at least one of these two models.8 Three standard mechanisms currently accepted for most of the established anticonvulsant drugs include conventional GABA facilitation, inhibition of sodium channels, or modulation of low-voltage-activated calcium currents.9

Pharmacokinetic properties must be considered for an ideal anticonvulsant drug. The drug should have rapid intestinal absorption after oral administration, good bioavailability, and should achieve a steady state within a reasonable period of time. In addition, the drug should have linear kinetics that produce predictable drug concentrations with minimal to no protein binding and limited drug-to-drug interactions. Last, the ideal anticonvulsant would have minimal to no hepatic metabolism, especially in patients with hepatopathy.10

ASSESSMENT OF THERAPY

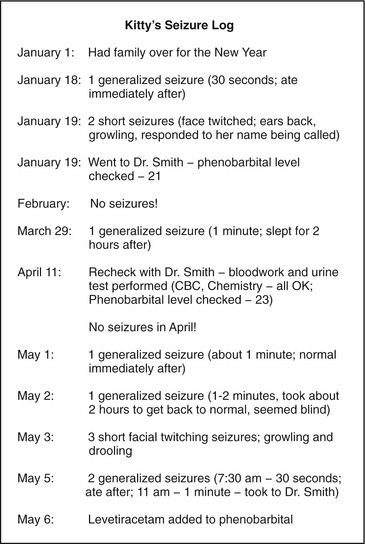

All clients should be encouraged to maintain a seizure log (Figure 54-2), detailing the number of seizures as well as unique features of the seizure (i.e., length of ictal and postictal periods, seizure type, events that may affect the environment). The log is reviewed during recheck visits. Physical and neurological examinations, monitoring of anticonvulsant drug concentrations, and laboratory evaluation should be performed about every 6 months, and may be more frequent in the initial stages of therapy.

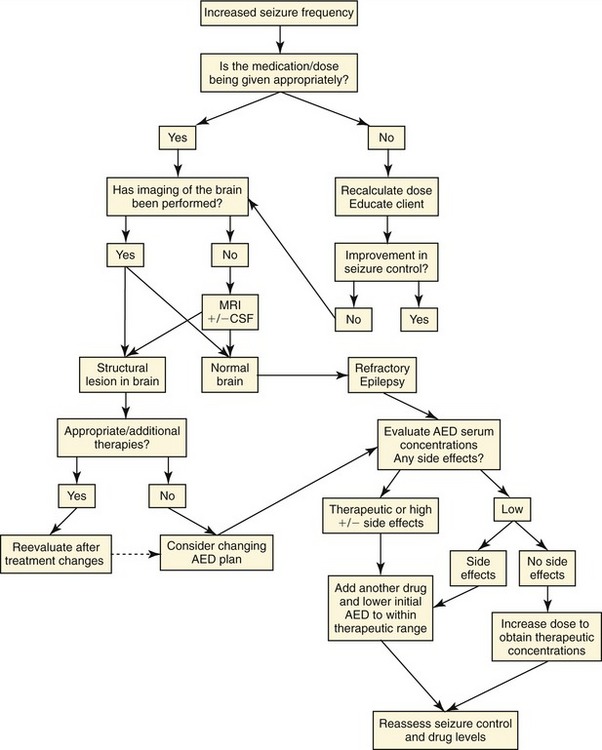

Defining successful response to an anticonvulsant drug is based on the individual cat. Therapeutic effectiveness of an anticonvulsant drug is considered when there is a reduction of number of seizures by 50 per cent or more. For example, a cat who had a seizure six times each month prior to therapy, and three times or less each month after therapy is considered to have had a favorable response to medication. When therapy is not effective, the treatment plan is reevaluated (Figure 54-3). Treatment failures are the result of progressive disease, refractory seizures, poor client compliance, inadequate drug dosing, and drug side effects and interactions. The first step in investigating reasons for treatment failure is to confirm the dose of the drug that is being administered. The drug dosage is reassessed and the treatment schedule is verified. The physical and neurological examinations are performed to ascertain underlying disease. If not already performed, diagnostic procedures are discussed with the client. Changes in anticonvulsant drug dosing are based on drug concentration within the therapeutic target range and associated side effects. If the drug concentration is low in the target range and side effects are minimal, increasing the dosage is a viable option. If the drug concentration is on the higher end of the target range or side effects are present, addition of another anticonvulsant is considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree