CHAPTER 62Normal Prefoaling Mammary Secretions

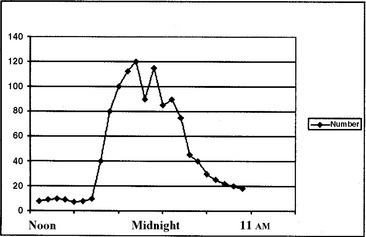

Normal gestational length can vary widely in the mare. The majority of mares foal during “nonbusiness” hours for most horse owners, as well as veterinarians. Thus many sleepless nights can be spent waiting up for the mare to foal. A 24-hour distribution of spontaneous foaling times for over 1,100 mares is depicted in Figure 62-1.1 Physical signs of the mare’s approaching readiness for foaling include a gestation length of greater than 320 days, udder enlargement with the presence of colostrum or milk in the teats, waxing on teat ends, and relaxation around the tail head, buttocks, and lips of the vulva. Although helpful, none of these signs is extremely accurate as a means of predicting when the mare will actually foal.

Figure 62-1 The distribution in a 24-hour period of spontaneous foaling times for over 1,100 mares.

(Modified from Bain AM, Howey WP: Observations on the time of foaling in Thoroughbred mares in Australia. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 1975; 23:545)

Studies of prefoaling milk (mammary secretion) electrolyte changes have demonstrated an association with the mare’s approaching readiness to foal.2–11 These electrolyte changes, especially with regard to calcium, have also been related to the development of maturity of the foal in the uterus and its subsequent survivability (i.e., viability) following a normal delivery.4,8,10,12,13

Prefoaling mammary secretion electrolytes are related to fetal readiness for birth.4 Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content of such samples has been shown to be both sensitive and specific.10 The predictive value of a positive test (PVPT) (defined as the first occurrence when CaCO3≥ 200 ppm) was determined to be 97.2%, for normal pregnant mares foaling spontaneously within 72 hours. Mares with placentitis and other causes of precocious lactation, however, have early elevation of mammary secretion calcium.14 Before 310 days’ gestation, elevated milk calcium levels indicate placental abnormality and not fetal maturity.

It has been suggested that the inversion of sodium and potassium concentrations in prefoaling mammary secretion does not occur in mares experiencing placentitis and may be a better indicator of in utero fetal maturation.15 However, no published reports could be found to support this hypothesis other than the very early work of Peaker et al and Ousey et al.2,4 These both used normal, spontaneously foaling mares for their investigations. We repeated this work (a) to evaluate prefoaling mammary secretion sodium and potassium concentrations and (b) to document the time of their relative inversion before foaling in normal mares. A consistent pattern could not be demonstrated16; 5 of 14 mares foaled normally, delivering live, healthy foals, and none demonstrated a sodium to potassium electrolyte inversion on any sample collected daily or twice daily from 7 to 10 days before spontaneous parturition. In a more recent work, it was reported that concentrations of potassium, calcium, citrate, and lactose increased and concentration of sodium decreased as foaling approached but that variation between mares was large.11 These authors concluded that the use of prepartum equine mammary secretion electrolyte concentrations for prediction of time of foaling is unreliable due to the large variation in both absolute and change in electrolyte concentrations between mares. This is absolutely correct. None of these methods has yet been shown to predict time of foaling. Ley et al10 stated that prefoaling mammary secretion CaCO3testing is a helpful prognostic tool to indicate the mare’s approaching readiness for birth and a method to predict when the mare is not likely to foal within 24 hours when the CaCO3is less than 200 ppm. Ousey et al4 suggested by their results that fetal maturity may be related to electrolyte concentration in mammary secretion and that an ionic score greater than or equal to 35 may indicate that induction would be successful in terms of maturity of the newborn foal. Leadon et al3 stated that calcium concentrations of the mammary secretions proved useful in predicting full term and also in assessment of the chances of foal survival in prematurely induced parturition. Ousey et al9 in a later report stated that mammary secretion electrolyte testing before foaling was not particularly accurate in predicting time of parturition, although it was a reliable means of indicating when it was not necessary to attend prepartum mares at night. It is reasonable to agree with Douglas et al11 that these tests do not predict foaling time. Very few investigations have actually claimed that they do. Prefoaling mammary secretion electrolyte testing methods are simply a means to evaluate in utero fetal maturation and the approaching readiness for birth.

The FoalWatch test kit (CHEMetrics, Inc., Calverton, Va.) has been used extensively over many years by the authors and has proven useful in the routine management of mares in the prepartum period. Its intended use is to assist in determining when the fetus is likely mature in utero and the mare is approaching readiness for spontaneous foaling. This is based upon the ability of the kit to detect changes in the prefoaling mammary secretion (milk) CaCO3level. It is a tool that, when used in an appropriate manner, will allow one to attend the mare’s foaling without an excessive number of sleepless nights. Alternatively, it can be used as a tool for accurately assessing when elective induction of parturition may safely be attempted. The advantages of this methodology include its accuracy and repeatability compared with other test kits or test strips available on the market, its ease of use, its quantitative (numerical) determination of the CaCO3level in each sample of prefoaling milk tested, and its economy.

WHEN TO BEGIN TESTING THE MARE

Begin sampling udder secretions and testing the recovered fluid approximately 10 to 14 days in advance of the mare’s expected foaling date, calculated as 335 to 340 days from the last known breeding date. In mares with an unknown breeding date, testing should begin as soon as some udder enlargement is noted and a small amount of secretion can be obtained from the teats without undue effort. It is best to keep a close check on udder development on a daily basis and practice massage of the mare’s udder and teats to allow her to get used to being handled in this area. Once-a-day sampling is sufficient until values of CaCO3are greater than or equal to 100 ppm. Thereafter, twice-daily sampling is recommended. More accurate assessment of the mare’s readiness to foal will be from daily late afternoon to early evening sampling. Because a few mares will foal in the daytime (see Figure 62-1), a morning sample should not be neglected and is highly advisable when CaCO3values first are greater than or equal to 125 ppm.

TESTING PROCEDURE

The sample should then be taken to a clean, dry, and warm area for testing. A syringe is used to draw up exactly 1.5 ml of the sample. The measured sample is placed into a mixing vial, and exactly 9.0 ml of distilled water is added. This dilution (i.e., ratio of 1 part mammary secretion to 6 parts distilled water) of the prefoaling milk sample is important because it adjusts the calcium level within the milk to an appropriate range for testing. This must be carefully and accurately performed at all times. After the dilution is completed, 1 to 2 drops of an indicator dye solution supplied in the test kit is added to the diluted sample. The instructions supplied with the kit should be followed as described in the product insert. Attach the flexible end of the valve assembly over the tapered tip of the glass titret so that it fits snugly. Lift the control bar of the Titrettor, and insert the assembled titret into the body of the Titrettor (Figure 62-2). Hold the Titrettor with the flexible pipet tip in the solution for testing, and press the control bar gently to break the prescored tip of the glass titret tip. (note

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree