Chapter 10 Nonobstructive Idiopathic or Interstitial Cystitis in Cats

Terminology

Feline Urological Syndrome (FUS) and Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease (FLUTD)

1. Previously used terminology is confusing and reflects a lack of understanding of the etiopathogenesis of this syndrome.

2. These terms originally were used to describe a syndrome in cats characterized by pollakiuria, stranguria, hematuria, and inappropriate urination.

3. They are nonspecific terms and do not indicate if clinical signs arise from the bladder, urethra, or both.

Feline Idiopathic Cystitis (FIC)

1. Describes signs of abnormal or irritative voiding behavior associated with absent or minimal cellular inflammation in the lower urinary tract. This type of inflammation is called neurogenic and is characterized by vasodilatation, edema, vascular leakage, diapedesis of red blood cells, but minimal inflammatory cellular infiltration.

2. FIC is a diagnosis of exclusion made after ruling out urolithiasis, bacterial urinary infection, anatomic abnormalities, behavioral disturbances, and neoplasia.

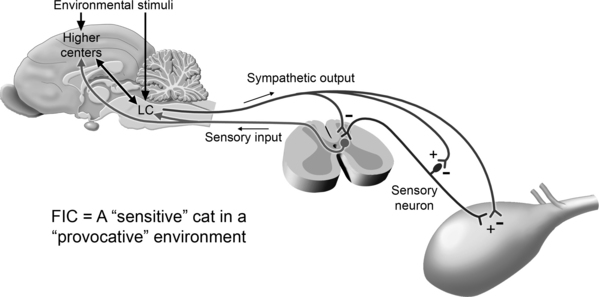

3. The disease process is multifactorial and involves interactions among the bladder, other organs (e.g., adrenal glands), the central nervous system (CNS), husbandry practices, and the environment.

5. In severe cases, affected cats may have a variety of comorbid disorders, and lower urinary tract signs are a manifestation of some underlying disorder.

Interstitial Cystitis

2. Original guidelines for diagnosis required visualization of glomerulations (submucosal petechial hemorrhages) by cystoscopy, but these findings are no longer required for diagnosis.

3. Interstitial cystitis refers to a chronic condition that waxes and wanes in severity and often is exacerbated by stress. Flares are acute episodes of clinical signs superimposed on the underlying chronic condition.

Pathophysiology

A. The pathophysiology of chronic FIC is not completely understood, but appears to involve abnormalities in many body systems including the bladder, nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and possibly other body systems. Bladder lesions observed in cats with FIC may be a result of abnormalities in other body systems and not the actual cause of the disease.

B. Little is known about the acute pathophysiology of FIC because clinical signs often spontaneously resolve in <5 to 7 days even without treatment. Most studies have focused on cats with recurrent FIC.

C. Subclinical systemic abnormalities persist in cats with recurrent FIC even when clinical signs are not present.

1. Urothelial integrity, bladder permeability, glycosaminoglycan (GAG) excretion, adrenal function during stress, and CNS function are all abnormal in cats with FIC even when detectable clinical signs are not present.

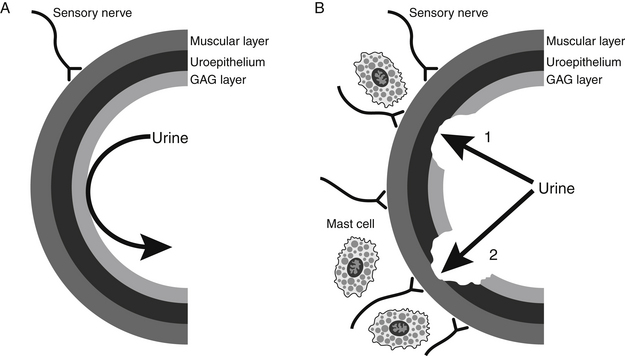

E. Urothelial integrity is compromised in chronic FIC, and this change may be an initiating or perpetuating factor in the disease process (Figure 10-2).

1. In a normal bladder, GAG (specifically GP-51) contributes to the mucous layer that coats the intact urothelium and provides a barrier that inhibits bacterial attachment and repels noxious substances in urine, thus preventing urothelial damage.

2. Chronic FIC is characterized by a decrease in urinary GAG excretion. In some but not all studies, this is seen to occur as a result of decreased GAG synthesis or increased GAG adherence to damaged uroepithelial cells. The underlying reason for these changes in GAG and the uroepithelium is unknown. Whether the change is a primary abnormality or secondary to other changes in the bladder remains to be determined.

3. Decreases in the urothelial GAG layer may lead to an increase in bladder permeability allowing noxious substances in urine to permeate the bladder wall, causing tissue irritation and activation of the nervous system.

a. Urine can be damaging because of its high osmolality, low pH, and the presence of noxious waste products.

b. No single urinary component has been identified as the cause of irritation to the bladder mucosa.

c. Sensory neurons in the bladder wall are stimulated by urine and may contribute to nervous system abnormalities.

F. Sensory neuron abnormalities.

1. C-fiber sensory neurons in the bladder are more sensitive in cats with FIC than in normal cats and contribute to altered activation of neural pathways.

a. Sensory neurons innervate the bladder via the pelvic and hypogastric nerves, which originate from the dorsal horn of the sacral and lumbar spinal cord, respectively.

1. Altered activity in the locus coeruleus (LC), Barrington’s nucleus, and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus increase sympathetic outflow.

2. The LC is the most important source of norepinephrine in the feline CNS.

c. Chronic activation of this pathway increases levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of catecholamines, in the LC.

d. Increases in TH contribute to increases in norepinephrine in cerebrospinal fluid and nervous tissue, bladder and colon, plasma, and urine in cats with FIC.

H. Stress, inflammation, and bladder pain are key components of FIC that are integrated at the level of the sympathetic nervous system.

2. Environmental stressors combined with increased sympathetic activity play a key role in the disease process.

a. Even in healthy animals, stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, which may initiate and perpetuate inflammation.

b. Norepinephrine contributes to vigilance, arousal, analgesia, and visceral responses to stress in cats.

c. In FIC, increased THIR and the corresponding increase in plasma norepinephrine concentration indicate an exaggerated sympathetic response even in the absence of stress.

d. This finding may explain why cats with FIC often exhibit a disease course that waxes and wanes and why environmental stressors intensify clinical signs.

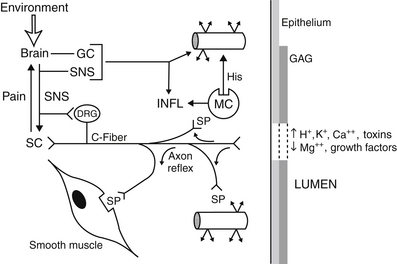

2.  Increased sympathetic outflow to the bladder alters urothelial permeability and initiates neurogenic inflammation via C-fibers (Figure 10-4).

Increased sympathetic outflow to the bladder alters urothelial permeability and initiates neurogenic inflammation via C-fibers (Figure 10-4).

a. Increased urothelial permeability allows noxious components of urine to gain access to the bladder wall and activate C-fibers.

b. Increased C-fiber activity initiates local inflammatory pathways that lead to vasodilatation and mast cell infiltration.

3. Alpha 2-adrenoceptors also appear to function abnormally in cats with FIC in ways that may enhance inflammation.

a. Alpha 2-adrenoceptors are found throughout the CNS, including in the LC and spinal cord. Receptors in the brain function to prevent catecholamine release and those in the spinal cord dampen nociceptive input to the brain.

b. Peripheral alpha 2-adrenoceptors can be found in the bladder and urethral mucosa, where they regulate blood flow.

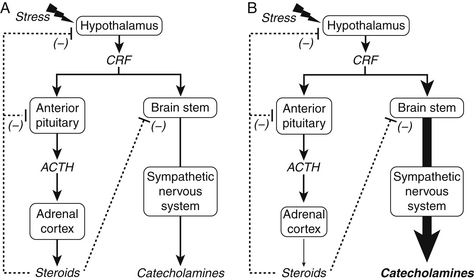

2. Increased concentrations of corticotropic-releasing factor and ACTH and an impaired cortisol response have been identified during periods of stress in cats with FIC (Figure 10-5).

3. Decreased adrenal corticosteroid production may be involved in the pathogenesis of FIC.

a. During stressful situations in FIC cats, a disproportionate activation of sympathetic outflow may occur because of the deficient adrenocortical response.

4. Glucocorticoid therapy does not provide any long-term benefit to cats with FIC, indicating that inadequate production of other adrenal steroids may play a role in the pathophysiology. Only cortisol has been studied thus far.

5. Decreased adrenal gland volume per kilogram of body weight was found in cats with FIC compared with healthy cats.

b. The zona fasciculata and zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex (areas responsible for corticosteroid production) were significantly smaller in FIC cats compared with healthy cats.

Signalment

Clinical signs

A. We use the acronym “FISH” to describe the principal lower urinary tract signs associated with idiopathic cystitis:

2. Inappropriate urinations. Also called periuria (i.e., urinating outside the litter box). This is the most common clinical sign reported by owners, and in some cases may be the only reported sign.

C. The development of clinical signs appears to require the presence of predisposing internal abnormalities (i.e., brain, bladder, adrenal glands) as well as external factors (i.e., stressors) that bring the cat to a threshold at which clinical signs will be exhibited.

Differential diagnoses

Cats Younger Than 10 Years of Age

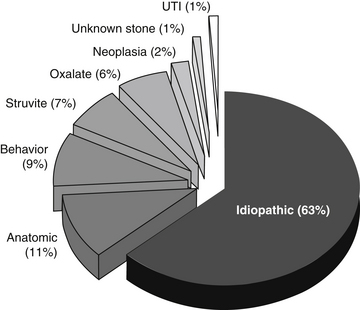

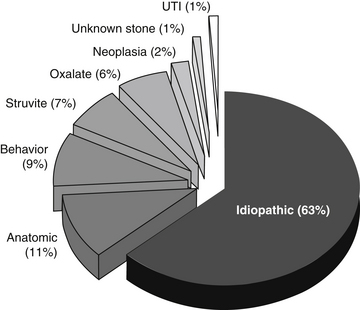

1. FIC accounts for 60% to 70% of cats presented for clinical signs of irritative voiding (Figure 10-6).

FIGURE 10-6 Distribution of diagnoses in young cats presented for signs of lower urinary tract distress.

(From Buffington CA, Chew DJ, Kendall MS, et al: Clinical evaluation of cats with nonobstructive urinary tract diseases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 210:46-50, 1997.)

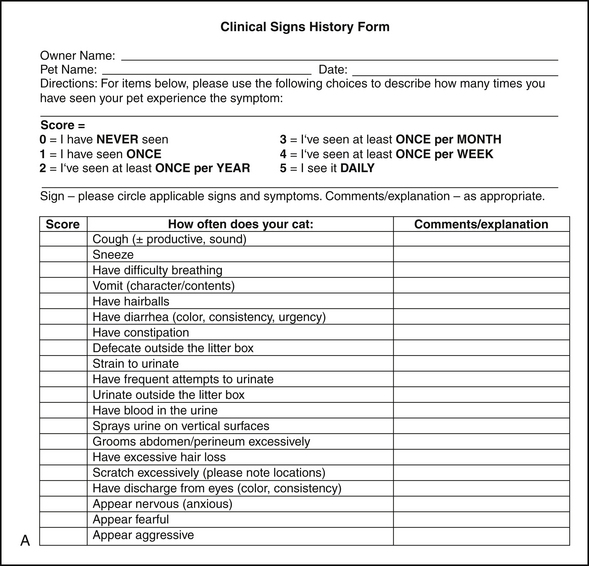

History

B. Effective client communication will facilitate accurate diagnosis and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

C. Establish a bond with the client, ask open-ended questions, practice reflective listening, and provide empathic statements to obtain a thorough history and build client confidence.

D. Ask questions about early adverse events the cat may have experienced and that may serve as vulnerability factors (e.g., maternal stress, orphaned, bottle-fed, early neutering).

F. Gather information about litter box use and maintenance.

1. Number and location.

a. Cat owners should have one litter box for each cat (or cat group) in the household plus one additional box.

4. Automatic cleaning. Although these devices keep litter boxes clean, some cats are frightened by the noise created by the machine.

5. Type of litter used and how often the owner changes the litter.

6. Cleaning schedule.

a. How often is the box scooped for urine and feces (i.e., once daily, twice daily, every other day, weekly)?

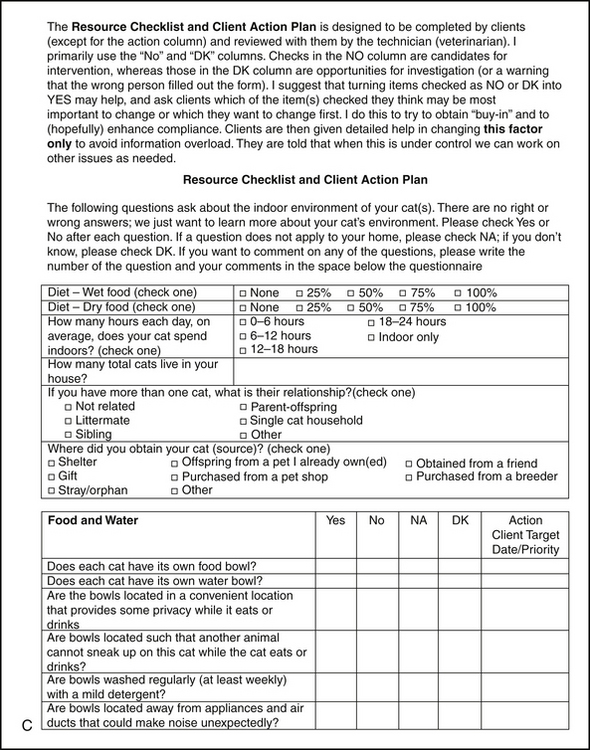

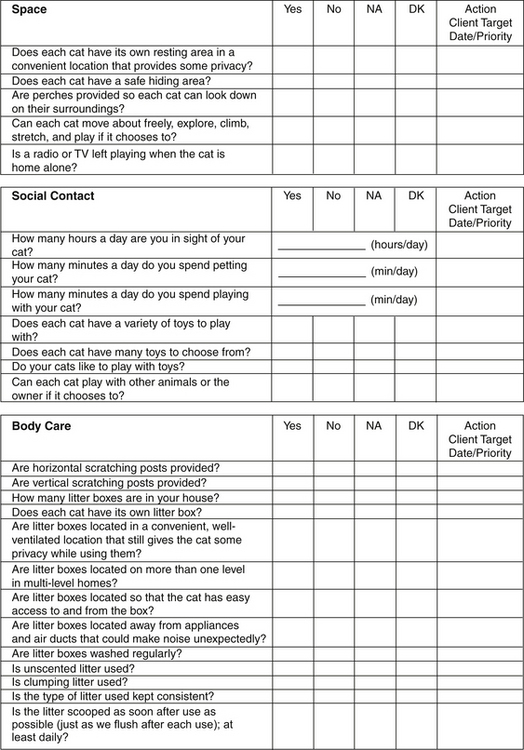

C, Resource Checklist and Client Action Plan.

(Developed by the Indoor Cat Initiative, The Ohio State University [www.vet.ohio-state.edu/indoorcat.htm] and used by permission.)

b. Paw markings on the carpet around the urine spot suggest an attempt to cover the area (a normal behavior associated with urination).

e. Toileting problems may indicate the cat has developed an aversion to the current litter. Aversion to a particular litter type can develop during acute episodes of FIC, after which the cat may associate a particular litter type with painful attempts at urination. Toileting in only one location suggests litter box avoidance.

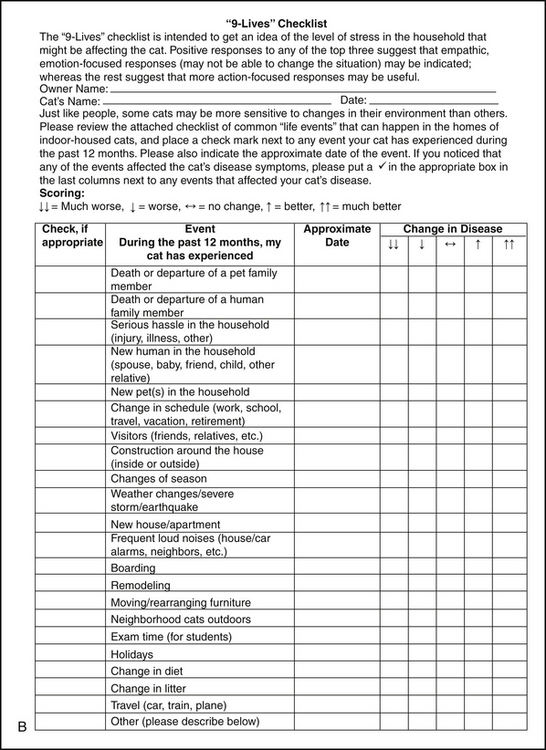

H. Stress in the cat’s or owner’s life should be identified if possible during the history because stress can play an important role in initiating and perpetuating clinical signs. Determination of the degree of stress in an individual cat’s life can be difficult.

1. Moving to a new living space or a change in the owner’s schedule are very stressful experiences for a cat.

2. Many other stressors are possible and may arise from other animals, humans, the living space itself, and husbandry (e.g., diet, water, litter box).

3. Earthquakes and dramatic changes in weather conditions (as seasons change) also have also been reported to increase risk for episodes of FIC.

Physical Examination

A. Perform a complete physical examination of all other body systems before focusing on the urinary tract to ensure identification of all comorbid conditions that may be present.

C. A thickened bladder wall may be identified in some cats with chronic disease. During flares of FIC, the bladder will be small due to irritative voiding.

E. Excessive grooming or biting of the hair on the caudal abdomen may be a sign of referred pain in some cats (so-called barbering). Some cats also will pull hair out in clumps from the flanks and tail base.

F. Gallops, murmurs, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, obesity, odontoclastic resorptive dental lesions, gastrointestinal disease, and nervousness potentially are comorbid conditions that occur with increased frequency in cats with FIC.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree