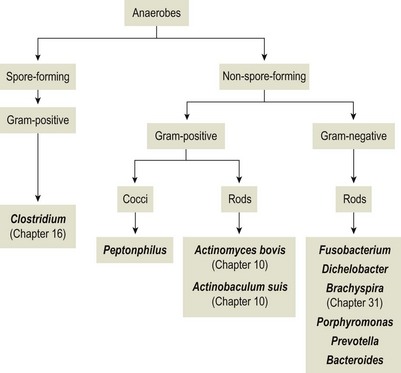

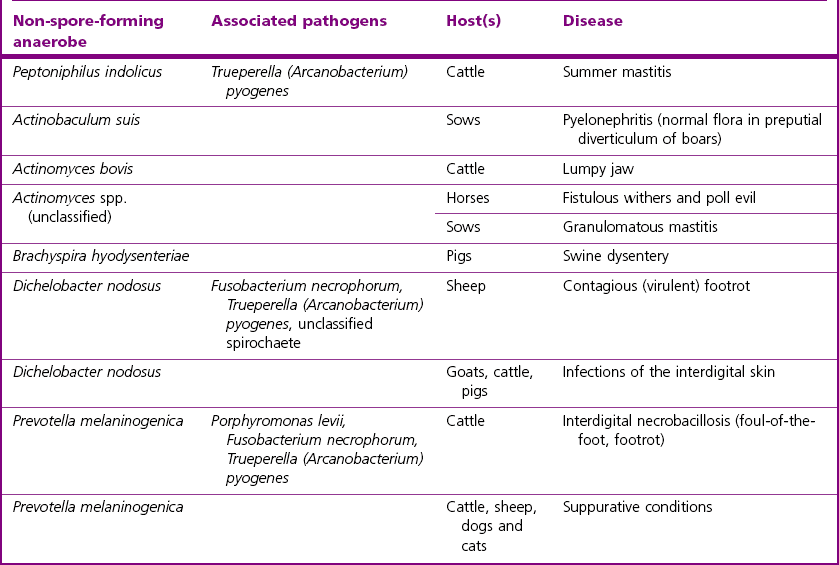

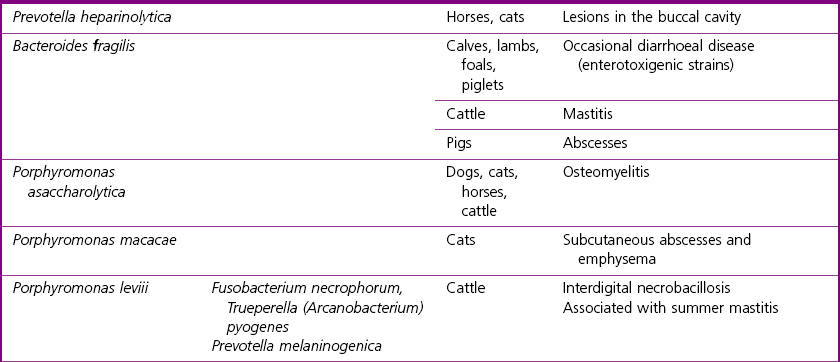

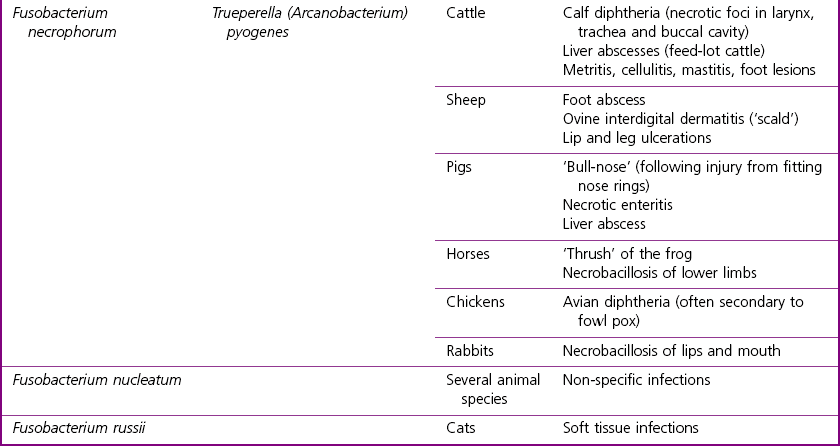

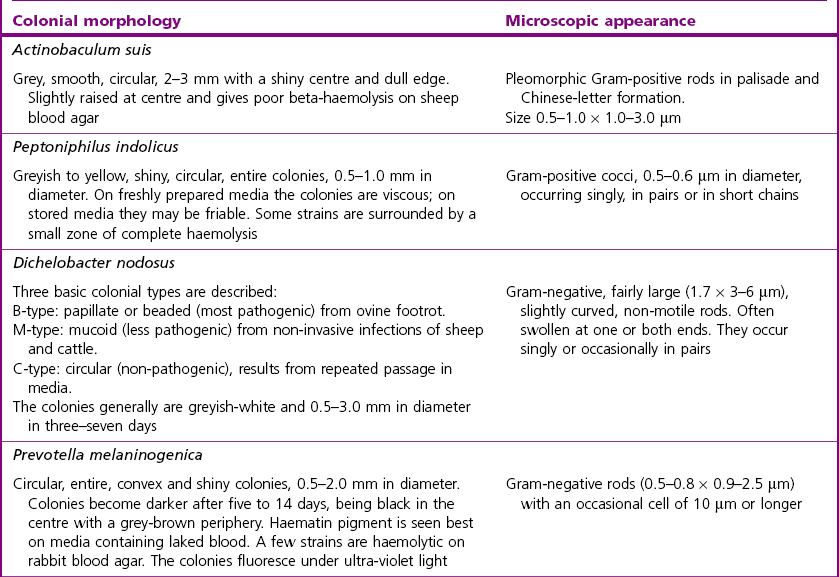

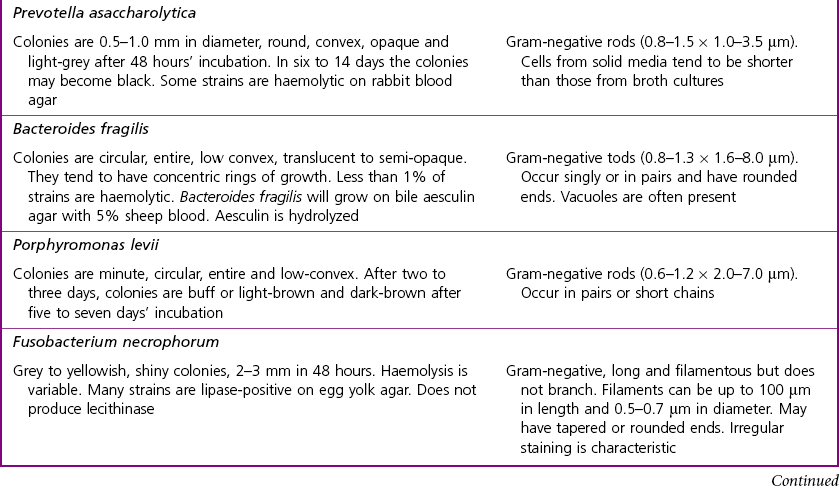

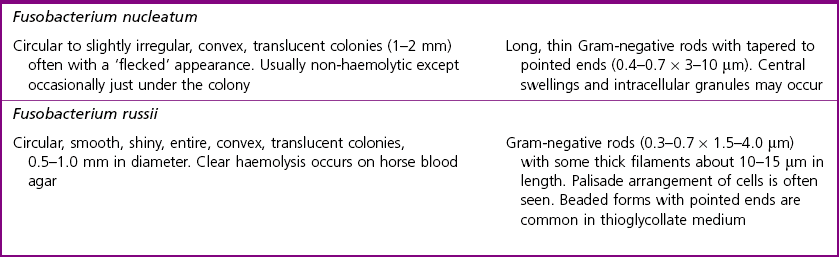

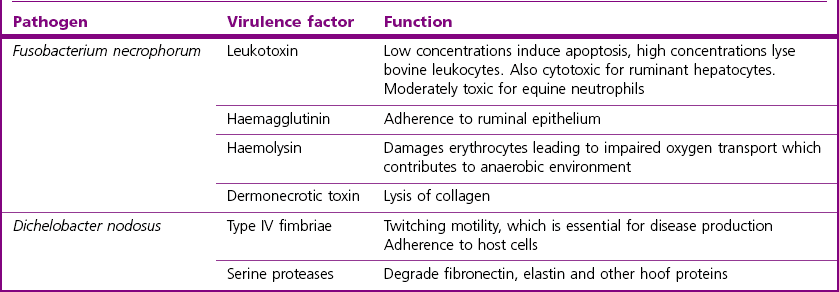

Chapter 15 The non-sporing obligate anaerobes constitute a large, diverse group of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria that exist in the environment but also as commensals on mucous membranes of animals and humans, particularly in the intestinal tract as part of the normal flora. Phenotypic characteristics are highly variable depending on the genus and species in question and are described under Laboratory Diagnosis and associated tables. Although knowledge of these bacteria is incomplete as they can be nutritionally demanding and require strict anaerobic conditions for isolation, more information is becoming available through the use of advanced molecular techniques. They are commonly implicated in necrotic and suppurative conditions, often as mixed infections with facultative anaerobic bacteria. Figure 15.1 briefly summarizes the more important genera of these non-spore-forming anaerobes. The infections are often endogenous from normal flora at the site or may be wounds contaminated by nearby flora. For these strict anaerobes to multiply at a focus in animal tissue the redox potential of the tissues must be lowered. This can occur through trauma and necrosis, ischaemia, parasitic invasion or concomitant multiplication of facultative anaerobes. The conditions caused by these non-sporing anaerobes include soft tissue abscessation and cellulitis, post-operative wound infections, periodontal abscesses, aspiration pneumonia, lung and liver abscesses, peritonitis, pleuritis, myometritis, osteomyelitis, mastitis and footrot. Some of the more common infections are shown in Table 15.1. The major pathogens of veterinary significance described in this chapter are Fusobacterium necrophorum and Dichelobacter nodosus, with organisms such as Prevotella spp. and Porphyromonas spp. being isolated from ruminant foot conditions and other necrotic or suppurative lesions. Brachyspira and Treponema spp. are described in Chapter 31 and Actinomyces bovis and Actinobaculum suis in Chapter 10. Fusobacterium necrophorum is a normal inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract and is a major cause of necrobacillosis in animals, particularly calf diphtheria, liver abscesses in cattle and necrotic and suppurative conditions of the foot in ruminants, pigs and horses (Table 15.1). There are two subspecies, F. n. necrophorum and F. n. funduliforme, with F. n. necrophorum being the more pathogenic. Its major virulence factor is a leukotoxin. This toxin, encoded by the gene lktA, is particularly effective against ruminant leukocytes and induces activation and apoptosis of these cells (Narayanan et al. 2002). Other important virulence attributes include the production of high levels of endotoxin, haemagglutinin production, and dermotoxic activity which may be due to a collagenolytic cell wall component (Okamoto et al. 2005, Tadepalli et al. 2009). Virulence of Dichelobacter nodosus, the primary causal agent in footrot of sheep, is dependent on the presence of Type IV fimbriae and the production of proteases (Kennan et al. 2011). The fimbriae are highly immunogenic and are classified into 10 major serogroups, designated A to I and M. In addition, strains of D. nodosus may be classified as virulent, benign or of intermediate virulence according to the clinical lesions and proteases produced. The fimA gene is essential for virulence in sheep and antigenic diversity of the fimbriae is based on variation in the carboxy-terminal of this gene. It has been suggested that serogroup conversion, possibly due to recombination following natural transformation, may occur in the field (Kennan et al. 2003). Such events would explain some of the difficulties encountered in control of footrot by vaccination and suggest that benign strains of D. nodosus may have importance as a source of alternative fimbrial antigens. A summary of major virulence factors of F. necrophorum and D. nodosus is given in Table 15.2. Table 15.2 Major virulence factors of the non-spore-forming anaerobes Fusobacterium necrophorum and Dichelobacter nodosus Specimens for the isolation of these strict anaerobes should be placed immediately in an oxygen-free container, especially small pieces of tissue or material taken on swabs. Appendix 2 describes the preparation of a modified Cary–Blair medium to be used with swabs sterilized and stored in an oxygen-free atmosphere. Gram-stained smears of the specimens are useful as a screening process, although many of these anaerobes are not morphologically distinctive. Dilute carbol fuchsin (4–8 minutes) stained smears are more useful for many of the Gram-negative species as they tend to stain faintly with the Gram-stain. Fusobacterium necrophorum in clinical specimens is long and filamentous (about 1 µm in diameter) and stains in a characteristically irregular manner (Fig. 15.2). Fusobacterium nucleatum appears as thin rods (3–10 µm long) with tapered ends, often occurring in pairs. Dichelobacter nodosus is a large rod characterized by the presence of terminal enlargements at one or both ends. Table 15.3 summarizes the microscopic appearance of some of the non-spore-forming anaerobes.

Non-spore-forming anaerobes

Pathogenicity

Laboratory Diagnosis: General

Collection of specimens

Direct examination

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Non-spore-forming anaerobes

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue