Chapter 5 Nervous system and special senses

Nervous tissue

Neuron structure

The main cell of the nervous system is the neuron (see Ch. 2, Fig. 2.16). Neurons are responsible for the transmission of nerve impulses throughout the nervous tissue. Nerve impulses pass from one neuron to another by means of structures known as synapses. All nerve pathways are made up of neurons and synapses. Complex nervous tissue, such as that of the brain and spinal cord, is made of neurons supported by connective tissue and neuroglial cells, whose function is to supply nutrients to and carry waste materials away from the neurons.

Each neuron consists of the following parts:

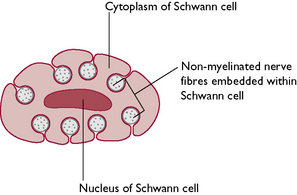

Nerve impulses from the dendrons are directed across the cell body towards the axon hillock and continue down the axon, reaching their final destination very rapidly. The speed of transmission along the axon is increased by the presence of a myelin sheath. Myelin is a lipoprotein material made by Schwann cells surrounding the axon. Its whitish appearance contributes to the colour of the more visible nerves in the body and to the white matter of the CNS. The myelin sheath is interrupted at intervals of about 1 mm by spaces known as the nodes of Ranvier and it is through these that the axon tissue receives its nutrient and oxygen supply. Non-myelinated fibres are embedded within the Schwann cells (Fig. 5.1) and despite their name are actually covered in a single layer of myelin. Totally uncovered fibres are rare and may be found in areas such as the cornea of the eye.

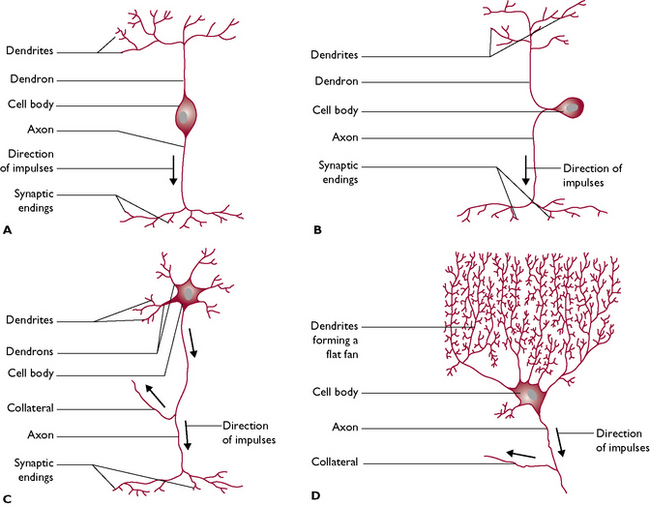

Neurons vary in size – the diameter of the axons and dendrons may be a few micrometres and the length depends on the destination of the nerve fibre. This may be anything from a few millimetres to more than a metre long. Neurons also vary in shape (Fig. 5.2).

Synapses

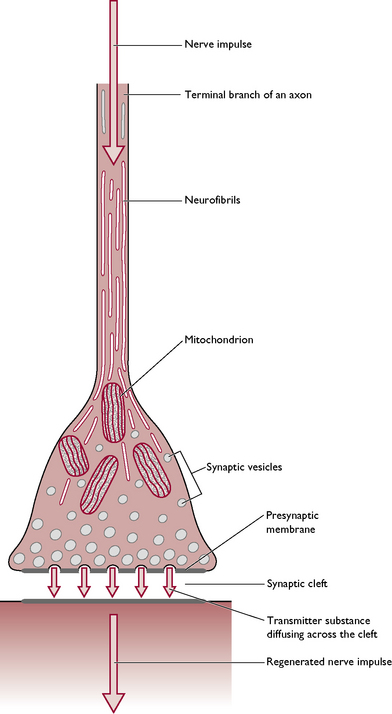

Each axon terminates in a structure called a synapse (Fig. 5.3). Where an axon terminates on an individual muscle fibre, the synapse is referred to as a neuromuscular junction and the nerve impulse stimulates contraction of the muscle fibre. Within the button-like presynaptic ending are vesicles containing chemical transmitter substances. The most common chemical is acetylcholine but others found in the body include adrenaline (epinephrine), serotonin and dopamine.

As the nerve impulse travels down the axon, the vesicles drift towards the presynaptic membrane (Fig. 5.3) and release the transmitter into the synaptic cleft. It diffuses rapidly across this gap and combines with the postsynaptic membrane, making the membrane more ‘excitable’ and allowing the transmission of the nerve impulse to continue on down the nerve fibre. The effect is stopped by the release of cholinesterases – enzymes that destroy any acetylcholine remaining in the synaptic cleft – and the synapse returns to its resting state ready for the next nerve impulse. Effective transmission of a nerve impulse across the synapse will only occur in the presence of calcium ions.

Generation of a nerve impulse

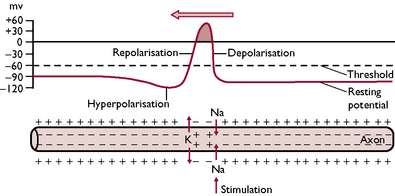

Nerve impulses transmitted along axons and dendrites can be considered to be electrical phenomena. An impulse changes the electrical charge of the neuron by altering the relationship between the negative charge of the cell contents and the positive charge of the cell membrane. This results from a change in the permeability of the cell membrane to sodium and potassium ions, causing an exchange of ions between the inside and the outside of the neuron (Fig. 5.4).

Classification of nerves

Peripheral nerves can be classified according to their function and to the structures they supply.

Nerve fibres may be further classified according to the organ with which they are associated.

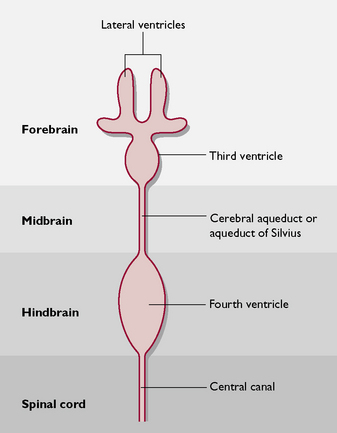

The central nervous system

During embryonic development of the CNS, a hollow neural tube forms from the ectodermal layer of the inner cell mass of the embryo. This neural tube runs along the dorsal surface of the embryo and, as it develops, nerve fibres grow out laterally extending to all parts of the body and eventually forming the peripheral nervous system. The anterior end of the tube becomes the brain and the remaining tube becomes the spinal cord. The brain and spinal cord are hollow and are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The brain

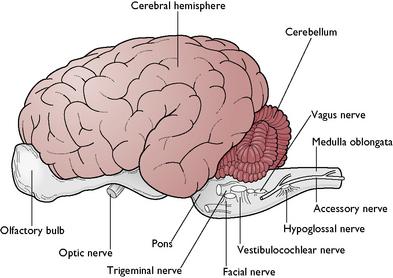

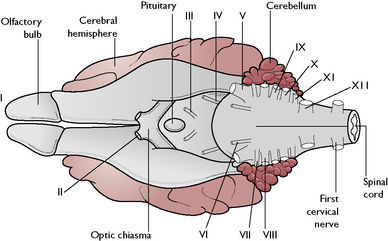

The function of the brain is to control and coordinate all the activities of the normal body. The brain is a hollow, swollen structure lying within the cranial cavity of the skull, which protects it from mechanical damage. In many species, three distinct areas can be identified – these are the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain. In mammals, this arrangement may be difficult to recognise because the right and left cerebral hemispheres of the forebrain are enlarged and overlie the midbrain (Fig. 5.5).

Forebrain

This consists of the cerebrum, thalamus and hypothalamus.

The cerebrum – or right and left cerebral hemispheres – takes up the greater part of the forebrain and contains up to 90% of all the neurons in the entire nervous system (Fig. 5.5). The right and left sides are linked by the corpus callosum. This consists of a tract of white matter whose nerve fibres run across the brain between the right and left hemispheres. It is found in the roof of the third ventricle, which is part of the hollow ventricular system inside the brain and contains CSF.

The tissue of the cerebral hemispheres consists of:

The hypothalamus lies ventral to the thalamus and has several functions:

On the ventral surface of the forebrain (Fig. 5.6) the following structures can be seen:

Midbrain

This is a short length of brain lying between the forebrain and the hindbrain. It is overhung by the cerebral hemispheres and is not easy to see in the gross specimen. It acts as a pathway for fibres running from the hindbrain to the forebrain carrying the senses of hearing and sight.

Hindbrain

This consists of the cerebellum, pons and medulla oblongata.

The cerebellum lies on the dorsal surface of the hindbrain (Fig. 5.5). Its name means ‘little brain’ as it was originally thought to be a smaller version of the cerebrum. It has a globular appearance and is covered in deep fissures. In cross-section, the tissue is very obviously divided into an outer cortex of grey matter and an inner layer of white matter. The grey matter consists of numerous Purkinje cells (Fig. 5.2), each of which forms thousands of synapses with other neurons.

The medulla oblongata extends from the pons and merges into the spinal cord (Fig. 5.5). It contains centres responsible for the control of respiration and blood pressure.

Protection of the brain

Cranium

This bony structure forms a tough outer shell to protect the soft brain tissue from physical damage.

Ventricular system

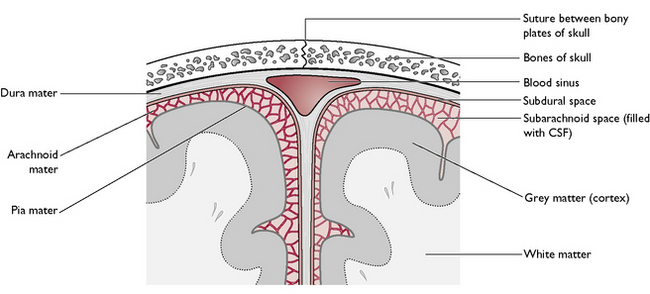

The ventricular system (Fig. 5.7) is derived from the hollow neural tube of the embryo. The lumen of this tube develops into a series of interconnecting canals and cavities or ventricles found inside the brain and spinal cord. The ventricles and the central canal are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This also surrounds the outside of the brain, lying in the subarachnoid space (Fig. 5.8). CSF is secreted by networks of blood capillaries known as choroid plexuses lying in the roofs of the ventricles. It is a clear fluid, resembling plasma, but has no protein in it – it is an example of a transcellular fluid. The function of CSF is to protect the CNS from damage by sudden movement or knocks and to provide nutrients to the nervous tissue of the brain and spinal cord.

Meninges

The meninges (Fig. 5.8) consist of three protective layers around the brain and spinal cord. From the outermost layer inwards, they are:

Blood–brain barrier

This is a modification of the neuroglial tissue that connects and supports all the neurons within the nervous tissue. Different types of neuroglial cells surround the blood capillaries, creating an almost impermeable layer, to protect the brain from substances that are harmful to or not needed by the brain. These include urea, certain proteins and antibiotics. Other materials such as oxygen, sodium and potassium ions and glucose can pass rapidly through the barrier to be used for brain metabolism.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree