Chapter 8 Neoplasia

The increasing popularity of ferrets as both pets and laboratory animals has facilitated the compilation of impressive collections of neoplasms that provides a fairly accurate look at the distribution of neoplasia in this species.4,16,36,37,44,60,62,68 In the previous edition of this book, the authors provided a review of common neoplasia as well as frequency data based on the extensive collection of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.68 With the current expansion of literature regarding neoplastic disease in this species as well as our desire to expand the discussion of available and emerging clinical treatments, frequency data of common neoplasms are presented based on the available literature for this species. Clinical discussion is derived from the authors’ clinical experiences as well as a comprehensive review of available literature. Space does not permit us to cover every type of neoplasm that has been reported in the ferret (as rarer and rarer tumors find their way into single case reports); thus we present only the major types of neoplasms, including their diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

Etiology

While we now have tremendous information on the frequency and distribution of neoplasia, there is still little definitive information on the causes of many common neoplasms in the ferret (as is often the case in human neoplasms). A large number of theories abound, but only rarely with supportive evidence. Three main schools of thought exist for ferrets, and it is likely that many neoplasms may be the result of several coexisting factors at once:

1. Husbandry issues. The “domestication” of the ferret as a pet species in many countries of the world involves varying degrees of environmental and surgical manipulation of the animal itself. Proof surrounding the effects of early neutering of ferrets and the subsequent development of adrenocortical neoplasia is now published and this mechanism is widely accepted.7,53,54 Dietary manipulation, especially the common practice of feeding high-carbohydrate diets and treats, has been suggested to be a primary cause for the increased incidence of insulinoma (when compared with the incidence in animals fed raw whole prey [rats, mice, etc.] as the dietary staple).53 Finally, the modern ferret owner’s predilection for indoor housing and artificial lighting may also play a role in the development of certain types of neoplasms. In Europe, where most ferrets are housed outdoors and exposed to natural lighting cycles, the incidence of neoplasia, especially adrenocortical, is greatly decreased.53 However, other factors, including delayed neutering, may also affect the development of neoplasia in European ferrets.

2. Genetic (familial) predisposition. While genetic or chromosomal aberrations are yet to be studied in domestic ferrets, the tremendous incidence of neoplasia in American bloodlines of ferrets as compared with their European counterparts certainly lends credence to this widely held belief. A recent case report by Fox22 documents a syndrome of multiple neoplasms in an adult ferret that closely resembles (multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2 in humans, a condition known to be the result of a genetic point mutation.

3. Infectious agents. Suspicious cluster outbreaks of malignant lymphoma in laboratory colonies and rescue operations3,18 have sparked the investigation of a possible viral etiology for this neoplasm in ferrets. Transforming retroviruses are known to be responsible for the development of lymphoma in a number of other species, including humans, cats, and rabbits among others. Erdman20 demonstrated the transmissibility of this neoplasm between ferrets using cell-free inocula, thus furthering this theory, although a prolonged incubation time was required. Helicobacter mustelae, a ubiquitous inhabitant of the stomach of ferrets, has been circumstantially incriminated in the development of gastric adenocarcinoma33 (which is enhanced when coupled with the ingestion of chemical carcinogens as promoters)21,23 as well as in the development of gastric B-cell (MALT) lymphomas.17 In addition, a progression from chronic inflammatory intestinal disease to neoplasia has been proposed in cats.70

Incidence and Behavior

Most studies agree that the endocrine system appears to be the most common site of neoplasia in ferrets.8,36,37,68 Pancreatic islet cell tumors (also known as insulinomas) are the most common neoplasms overall, with adrenocortical neoplasms being the second most common.18,36,37,68 In all studies, lymphoma was both the most common hematopoietic neoplasm and the most common malignancy.8,36,37,68 Between 12% and 20% of cases in each study had multiple tumor types, with insulinoma and adrenocortical carcinoma being seen concurrently most often.8,36,37,68 However, the presence of multiple tumor types in an individual should not be interpreted as a neoplastic syndrome arising from a common tumorigenic mechanism. In a study of 66 cases in which ferrets had multiple concurrent neoplasms, Li36 found no evidence of an association between tumor type and multiplicity. Because endocrine neoplasia is extremely common in American ferrets today (and is increasing in global frequency), it comes as no surprise that middle-aged and geriatric ferrets have multiple tumors developing over time.

Tumors of the Endocrine System

Insulinoma

Insulinoma in the ferret exhibits a far different behavior than in the dog or cat.9,62 In the dog and cat, these are highly malignant neoplasms with marked metastatic potential, leading to a short survival time. In ferrets, these same neoplasms have low metastatic potential and tend to respond well to medical management for long periods of time; their removal may result in a symptom-free or medication-free interval.62 In truth, some reports have clouded the issue of metastatic potential of insulinoma in the ferret. True metastasis involves the translocation, either via blood or lymph, to another organ; this is seen in the dog and cat, where the metastasis of islet cell tumors to local lymph nodes, liver, or other visceral organs is common. Some papers have incorrectly referred to the additional development of insulinoma within the pancreas over time as “metastasis,” whereas recurrence would be a more appropriate term. Other papers have labeled islet cell tumors as malignant (“islet cell carcinomas”) based solely on microscopic features of the tumor cells without evidence of intraorgan translocation or recurrent disease.

The diagnosis of insulinoma is not exceedingly difficult in the ferret and is generally based on a combination of the characteristic clinical signs and a low fasting blood glucose level in the absence of a nonendocrine etiology (see Chapter 7). The hypoglycemia resulting from the inappropriate secretion of insulin by these tumors generally results in a constellation of neurologic signs ranging from mild (ataxia or disassociation from the surroundings) to severe (seizures, coma). Blood glucose levels of less than 60 mg/dL in the ferret are generally diagnostic for insulinoma even in the absence of clinical signs. Some individuals may present with a history of neurologic disease and a normal fasting blood glucose; in the early stages of this condition, insulin release may be sporadic and clinical signs may be intermittent. The determination of insulin levels is rarely indicated prior to institution of therapy and is of no value in cases where blood glucose is above 60 mg/dL. Therapeutic approaches for the treatment of insulinoma in ferrets are widely reported. In our experience, surgical excision is the preferred course of treatment for symptomatic animals with documented hypoglycemia. In a clinical study,62 partial pancreatectomy yielded the longest disease-free intervals and survival times (365 and 668 days, respectively), followed by simple nodulectomy (234 and 456 days, respectively), although surgery did not eliminate the need for concurrent medical management in all cases. Medical treatment alone resulted in a mean disease free interval of 22 days and a mean survival time of 186 days.

Adrenocortical Neoplasms

The second most common neoplasm in the domestic ferret is also of endocrine origin and originates in the adrenal cortex. In the intact ferret, seasonal stimulus of the hypothalamus results in liberation of a range of hormones, including luteinizing hormone, which stimulates sex steroid production from the ovaries or testes. In neutered animals, the absence of gonads results in a lack of negative feedback for the hypothalamus and, under constantly elevated levels of luteinizing hormone, pluripotent cells of the zona reticularis differentiate into cells capable of producing estrogen and other intermediate sex steroid metabolites, including androstenedione and hydroxyprogesterone.7,52 Multiple studies have reported the average age of ferrets with adrenal disease at approximately 4.5 years,8,61,68 but the disease has also been reported in ferrets under 12 months of age,36 with no gender predilection.

The relatively obvious clinical signs exhibited by most ferrets with adrenal disease contribute significantly to the frequency of their presentation for treatment. Affected ferrets exhibit a constellation of cutaneous, behavioral, and reproductive signs that make them easily identifiable. Follicular atrophy resulting from excessive levels of estrogen results in a characteristic bilateral truncal alopecia in about half of affected animals, although irregular, patchy hair loss may be a presenting sign in a minority; in rare cases, no alopecia is appreciated. Vulvar swelling, similar to that seen in females in estrus may be seen in up to 90% of affected neutered jills, although absence of vulvar swelling does not rule out this disease.51,57 The effects of estrogen on the prostatic glandular epithelium in male ferrets may result in dysuria due to prostatic cysts or abscesses; if not treated promptly, azotemia, obstruction, and ultimately uremia are probable sequelae. Finally, the presence of elevated levels of testosterone in the male or estrogen in the female may result in a return to intact sexual behavior such as mounting, urine marking, and aggression.

To confirm enlargement, determine affected side, and screen for concurrent disease. For best detail, use a 14.5-MHz probe. Look for the right adrenal gland medial to the cranial pole of the right kidney, cranial to the origin of the cranial mesenteric artery, and adjacent or adherent to the caudal vena cava. The left adrenal gland is cranial and medial to the cranial pole of the left kidney, lateral to the aorta, and cranial to the left renal artery. Adenomas and adenocarcinomas can occur and cannot be differentiated without histopathology.6

Laboratory evaluation of circulating sex steroids is occasionally performed in cases where clinical signs are subtle or may be masked by concurrent disease. Estrogen, androstenedione, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone have been identified as the most sensitive hormones for the detection of adrenocortical lesions in the ferret and are over 95% predictive in the diagnosis of adrenocortical disease in this species.51 Practitioners are cautioned that hyperadrenocorticism in ferrets is not a form of Cushing’s disease, and cortisol testing is not useful in routine diagnosis. Elevations in cortisol52 and even aldosterone13 levels have been documented in ferrets with adrenal neoplasia, but these are rare and inconsistent findings and are not considered diagnostic.

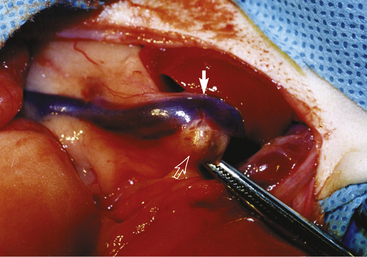

From a surgical standpoint, the incidence of the lesion appears equivalent between the left and right adrenal glands, and approximately 20% are bilateral.68 A wide range of surgical approaches exist for removing affected adrenal glands, and surgery is considered the treatment of choice for this condition.64 Because of its proximity to the vena cava (Fig. 8-1), surgical excision of the right adrenal gland often proves to be a challenge for most practitioners; a range of successful surgical options—including cryotherapy, laser dissection, and microvascular techniques—has been described for right adrenalectomy in the ferret.68 In cases where the neoplasm occludes the vena cava by 50% or more, the neoplasm and the affected section of vena cava may be excised en bloc, but this is not recommended by the authors. Excision of the vena cava carries a high risk of complications including renal failure and death, and these risks are greater than the risk of death from adrenal disease. While presurgical ultrasound examination may be used to identify the side (or sides) at which an affected neoplasm is located, the absence of adrenomegaly or an identifiable nodule via ultrasound does not obviate the need for surgery in affected individuals, since functional lesions may be present in normal-sized adrenal glands.6

Several options for medical management have emerged in recent years (see Chapters 7 and 11 for more in-depth discussions of surgical and medical treatments).

From a histologic (and prognostic) standpoint, proliferative lesions in the adrenal cortex of affected individuals fall into a spectrum ranging from hyperplastic lesions to benign or malignant neoplasms. A good prognosis appears warranted in the case of all surgically removed lesions, regardless of location (right vs. left), histologic grade, or completeness of excision.57,68 However, in all cases caution owners that lesions in the contralateral adrenal gland occasionally develop, resulting in recurrent disease at a later date, and metastatic disease may be seen in a low percentage of highly anaplastic carcinomas.46 Medical treatment, largely directed at decreasing circulating levels of sex steroids in affected animals, is generally reserved for nonsurgical candidates. These drugs are temporarily effective and are useful in ameliorating clinical signs; however, their effectiveness in halting the growth of established lesions or diminishing the risk of metastatic disease or hemoperitoneum associated with large tumors is still in question.60

Other neoplasms may be seen arising from adrenal glands in ferrets. First described in 1995,24 leiomyosarcomas of the adrenal capsule are often encountered in the ferret and may result in confusion on the part of the practitioner as well as the pathologist. These very firm neoplasms may lead practitioners to perform adrenalectomy on normally functioning adrenal glands. Unfortunately these cannot be differentiated without histopathology, so the practitioner is forced to make an intraoperative decision. The presence of the tumor may also mask the presence of proliferative adrenocortical lesions unless multiple sections at 1 mm or more are examined. These neoplasms have demonstrated estrogen receptors on the smooth muscle cells in several of these tumors, suggesting a possible etiology for their development as well as the common finding of smooth muscle proliferation in adrenocortical tumors.41

Thyroid Neoplasms

Thyroid neoplasms are extremely uncommon in this species. Nonfunctional thyroid follicular adenocarcinoma was reported in one ferret with infiltration into the surrounding tissue,69 and another was found with metastasis to cervical lymph nodes and liver.10 One case of a C-cell carcinoma22 (seen along with concurrent adrenocortical adenoma and insulinoma) has been reported. Clinical signs were not observed.

Tumors of the Hemolymphatic System

Lymphoma (malignant lymphoma, lymphosarcoma) is the most common malignancy in the domestic ferret and the third most common neoplasm overall (after islet cell tumors and adrenocortical neoplasia). Lymphoma denotes solid-tissue tumors composed of neoplastic lymphocytes in visceral organs or lymph nodes throughout the body. These neoplasms most commonly arise spontaneously; however, horizontal transmission of malignant lymphoma in ferrets by using cell or cell-free inoculum has been documented.20 This finding, coupled with the occasional clustering of lymphomas in a single facility, has prompted speculation that some variants of lymphoma in the ferret may be the result of a retroviral infection.19 A viral agent has not as yet been isolated from cases of lymphosarcoma in the ferret, and associations with feline leukemia virus and Aleutian disease (parvovirus) have been disproved.18,20

Classification of Lymphoma

Today there is substantial variation in the classification of lymphoma, which leads to a lack of consistency in the evaluation of any form of cumulative data for comparison of disease or prognostic outcome. There is no universally accepted classification scheme for ferrets; even among dogs and cats, pathologists differ in the descriptive information they routinely include in histopathology reports. As an example of the importance of a uniform system, three papers have described ferret lymphomas as low-, intermediate-, and high-grade, but each paper uses different criteria to define “low” and “high,” creating inconsistency in our ability to interpret or compare.1,16,43

All diagnostic workups should include both grading (histologic description in as much detail as possible) and staging (classification of disease) information. Ideally, phenotyping (immunohistochemistry to define cell origin) would also be included, although this is not yet routine in general clinical practice. Grading provides a histologic description based on cell morphology independent of phenotype (B-cell or T-cell). This provides indices like low, intermediate, and high grade based on cellular size and mitotic indices. The most commonly accepted grading system in companion animal medicine is the National Cancer Institute Working Formulation (NCI-WF), which differentiates cells based on morphology.39,43 There is still some discrepancy, so we recommend following a standard protocol (Table 8-1).

Table 8-1 Recommended Grading System for Ferret Tumors Based on Cell Morphology

| Nuclear size (relative to red blood cell [RBC] size) | |

|---|---|

| Small | ≤1 RBC |

| Medium | >1 but <3 RBC |

| Large | ≥3 RBC |

| Mitotic index (per high-power field) | |

| Low | <3 |

| Intermediate | 3-8 |

| High | >8 |

| Additional descriptive grading information that might also be included | |

| Nuclear morphology | Nucleoli |

| Round | Distinct |

| Indented/asymmetric/irregular | Indistinct |

Staging

This is a clinical description of the disease, providing information about the location of the neoplasia as well as its extent of dissemination throughout the body. The most commonly accepted staging system in veterinary medicine is the World Health Organization (WHO) staging system, which is also generally accepted by the American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVP). This system is based on descriptions of the clinical presentation, anatomic location, and disease progression (Table 8-2).39

Table 8-2 Staging for Lymphoma Based on Anatomic Location and Clinical Presentation

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| I | Affecting a single node or tissue in a single organ |

| II | Multiple lymph nodes in one area of the body (same side of the diaphragm) |

| III | Generalized lymph node involvement (both sides of the diaphragm) |

| IV | Any of the above + liver or spleen |

| V | Any of above + blood or bone marrow |

In cats, a secondary staging system is used based solely on anatomic location. This would also be extremely useful in ferrets, and we recommend that this information also be included in staging (Table 8-3).

Table 8-3 Anatomic Staging for Lymphoma

| Staging | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Multicentric | Multiple lymph nodes, usually on both sides of diaphragm May also involve liver, spleen, bone marrow, or other extranodal sites |

| Alimentary | Solitary mass within gastrointestinal tract or mesenteric node Multiple masses ± regional involvement of intra-abdominal node Diffusely infiltrating any part of bowel |

| Mediastinal | Mediastinal lymph nodes Not usually involving thymus |

| Extranodal | Other locations: Renal CNS Ocular Cardiac |

| Cutaneous | Sometimes included in extranodal |

Examples of appropriately staged and graded lymphoma in a ferret might be as follows:

• Stage: I, alimentary; Grade: small-cell, low mitotic activity, round nuclei, indistinct nucleoli

• Stage: IV, multicentric; Grade: large-cell, intermediate mitotic activity, round nuclei, distinct nucleoli

Lastly, if any neoplastic lymphocytes are present in the bone marrow or the peripheral blood, a diagnosis of lymphocytic leukemia is appropriate. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia indicates the presence of excessive numbers of mature (small) lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, with total leukocyte counts ranging from normal into the hundreds of thousands. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia indicates the presence of immature lymphocytes (lymphoblasts) in the bone marrow as well as in the peripheral blood, with leukocyte counts well in excess of normal. True lymphomas are far more commonly seen than leukemias, at a ratio of approximately 10:1.68

Phenotyping

Phenotyping defines tumor etiology as either B-cell or T-cell in origin. This can only be determined with the use of immunohistochemical stains or flow cytometry.27 CD3 is a T-cell marker, and CD79α is a B-cell marker. Although this information is useful, it is not routinely assessed in ferrets at this time. However, flow cytometric assays are becoming commonly used in companion animal medicine, and as phenotyping becomes a more standard part of a diagnostic workup, this may yield important prognostic information for ferrets.

Two other types of lymphoma should be discussed here. Cutaneous (epitheliotropic) lymphoma is of T-cell origin and possesses a mature lymphocytic phenotype and a profound affinity to infiltrate epithelial structures, such as the epidermis and hair follicles (Fig. 8-2). It alone among the ferret lymphomas does not warrant a poor prognosis at onset, as prolonged survival times (possibly up to 3-4 years) are associated with it, especially in cases where cutaneous lesions are rapidly surgically excised. Unlike epitheliotropic lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) in dogs and humans, the clinical picture does not necessarily progress to systemic involvement (Sézary’s syndrome). Epitheliotropic lymphoma is commonly seen in the feet and extremities of ferrets, resulting in grossly swollen, hyperemic, alopecic feet. Untreated, these lesions grow in size and multiple lesions will develop. Complete surgical excision of cutaneous lesions may result in prolonged disease-free intervals; chemotherapeutic attempts, both topical and systemic, have generally proved to be unsatisfactory.34,50

Gastric lymphomas, or mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, have been reported in four ferrets (see also Chapter 3).17 Considered akin to lymphomas associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in humans, these neoplasms arose in the stomach of ferrets infected with Helicobacter mustelae. An interesting feature of this proposed form of lymphoma is that although neoplastic cells varied in phenotype (two lymphocytic and two lymphoblastic forms), all four cases were composed of monoclonal B lymphocytes.17

Signalment and Clinical Signs

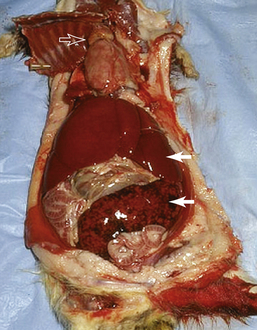

There is no universal signalment or clinical presentation for lymphoma in ferrets. It may occur at any age and has been reported in ferrets as young as 2 months of age. There is no color or sex predisposition. One paper historically reported that young ferrets (<2 years of age) develop a lymphoblastic form characterized by disseminated disease often involving spleen, liver, thymus, or mediastinum and rapid progression, while adult ferrets develop a slower, more insidious form consisting of mature, well-differentiated small lymphocytes that are accompanied by peripheral lymphadenopathy and slower progression.16 This paper has been quoted repeatedly throughout veterinary literature. However, there have been several more recent publications that failed to show this correlation. Although it was not the primary purpose of either investigation, these retrospective studies found that the lymphoblastic form exists commonly in all age groups (Fig. 8-3).1,43 In one paper, all multicentric lymphomas that were identified were comprised of blast cells and occurred largely in adult ferrets.43 Another paper identified visceral involvement in almost all ferrets necropsied, and again several ferrets representing all age groups had larger blast-like variants. Peripheral lymphadenopathy was rare, and again a correlation of the blast form to young ferrets was absent.1 Therefore the age of ferrets cannot be reliably used to determine type, extent, or prognosis for lymphoma.

Laboratory Evaluation

Anemia is the most consistent laboratory abnormality in ferrets with lymphoma.1 All the reported anemias were nonregenerative. Lymphocytosis and thrombocytopenia were extremely rare, and neutropenia was only occasionally identified.1 This indicates that results of CBCs and peripheral blood smears may yield valuable information in some cases but are rarely diagnostic for most cases of lymphoma. Persistently elevated lymphocyte counts cannot be used as evidence of lymphoma; as in other species, chronic smoldering infection is the most common cause of lymphocytosis in the ferret. The ubiquitous nature of Helicobacter and coronavirus infection in the U.S. ferret population has tremendous potential for inciting this nonspecific change in ferrets.

Plasma biochemical data are also inconsistent in patients with lymphoma, with abnormalities usually relevant to the location of the disease or organ involvement. One study found hyperproteinemia and hyperglobulinemia rarely in ferrets (all with T-cell lymphoma) and hypoalbuminemia in a small number of ferrets, correlating with small intestinal tumor. Hypercalcemia was present in 2 of 28 ferrets (both with T-cell lymphoma).1

Diagnostic Imaging

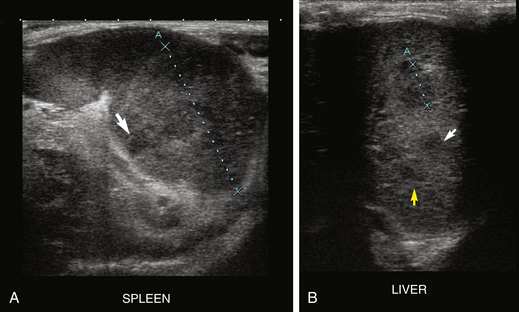

Ultrasonography is perhaps the most valuable clinical tool available to most practitioners in evaluating ferrets for lymphoma. In addition to evaluating the abdominal and mesenteric lymph nodes, ultrasound also enables the clinician to assess the liver, spleen, kidneys, mediastinum, and sometimes even the gastrointestinal (GI) tract for infiltration. Figure 8-4 shows a ferret with infiltrated liver/spleen; Fig. 8-5 shows a ferret with mesenteric lymphadenopathy (Figs. 8-4 and 8-5). In one author’s (NA’s) practice, all ferrets with alimentary lymphoma had sonographic evidence of mesenteric lymphadenopathy (not all ferrets with mesenteric lymphadenopathy had lymphoma; this is an important difference!). It is important to recognize that mesenteric and intestinal lymph nodes in ferrets often appear sonographically more prominent than those in dogs and cats, but this does not specifically indicate lymphoma. Even severely enlarged lymph nodes may represent diseases other than lymphoma. One paper evaluated ultrasonographic characteristics of the normal mesenteric lymph node in ferrets, which is described as round to ovoid, measuring 12.6 ± 2.6 mm × 7.6 ± 2.0 mm and uniformly hyperechoic.45 Once again, though, the absence of abnormality on ultrasound does not eliminate lymphoma as a possible diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree