Chapter 30 Navicular Disease

Pathophysiology of Navicular Disease

Navicular disease is a chronic forelimb lameness associated with pain arising from the distal sesamoid or navicular bone. It is well recognized that in association with advanced navicular disease, fibrillation of the dorsal aspect of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), with or without adhesion formation between the tendon and the navicular bone, is a common feature. Recent clinical studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)1 and post mortem studies2,3 have demonstrated that there may also be abnormalities of closely related structures, including the collateral sesamoidean ligaments (CSLs), the distal sesamoidean impar ligament (DSIL), and the navicular bursa. These structures and the navicular bone are called the podotrochlear apparatus. For the purposes of this chapter, this complex of degenerative changes will be referred to as navicular disease. Primary injury of the DDFT is considered to be a separate condition,4 which may have a different etiopathogenesis (see Chapter 32).

Biomechanical Considerations

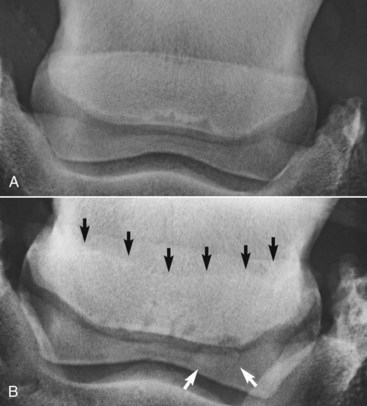

The shape of the navicular bone may be determined at birth, and this may influence the biomechanical forces subsequently applied to the bone (Figure 30-1) and hence influence the risk of development of navicular disease.6,19 Finnhorses and Friesian horses tend to have a straight or convex contour of the proximal articular border of the navicular bone and rarely develop navicular disease. There is a much higher incidence of navicular disease in the Dutch Warmblood breed, and horses in which the proximal articular margin is concave or undulating appear to be at highest risk of development of the disease.5,6

Histopathological Studies

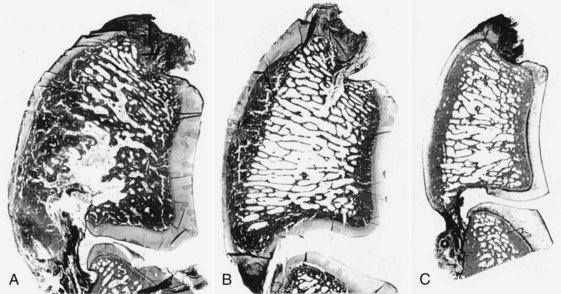

Navicular disease has not been reproduced experimentally; therefore all proposed etiologies remain speculative. Earlier theories suggesting a vascular etiology with arteriosclerosis20 or thrombosis, resulting in ischemia within the navicular bone,21 have largely been rejected because of failure to identify ischemic bone or thrombosis, failure to reproduce clinical signs or pathological changes by occluding blood supply to the bone, and expanding evidence demonstrating increased bone modeling.22-25 Post mortem studies to date have focused principally on horses with long-term, chronic disease, generally with advanced radiological abnormalities, reflecting the end stage of a disease complex. These studies identified striking similarities between the pathological features of navicular disease and osteoarthritis (Figure 30-2) in both people and horses.24,25

Entheseous Changes

The presence of entheseous new bone on the proximal border of the navicular bone, reflecting previous insertional desmopathy of the CSL, is well documented radiologically37,38 and at post mortem examination25,37 in both clinically normal horses and horses with navicular disease. Its clinical significance remains uncertain, although more extensive new bone in this location tends to be associated with other signs of navicular disease.37,38 Recent experience with MRI has confirmed these findings.1 Rarely, an avulsion fracture is identified at the insertion of the CSL into the navicular bone.8,39 Mineralized and osseous fragments (Figure 30-3) in the DSIL have also been recognized in both normal horses and in horses with navicular disease, and their clinical significance remains difficult to determine. Fragments were unusual in sound horses undergoing prepurchase radiographic examination,40 although their true incidence may be underestimated by radiographic examination compared with MRI or computed tomography (CT). In two post mortem studies, fragments associated with a defect in the distal margin of the navicular bone were more common in horses with navicular disease than in age-matched controls.2,25 This has also been my clinical experience.