Chapter 112National Hunt Racehorse, Point to Point Horse, and Timber Racing Horse

Description of the Sport

Hurdle races are held over fences smaller than those encountered in steeplechasing. In Britain, most hurdles are derived from the simple portable fences used to create temporary pens for sheep, although small brush hurdles are being trialed. They are usually 72 inches (1.83 m) wide and must be not less than 42 inches (107 cm) from top to bottom bar and constructed of ash or occasionally oak. Several hurdle sections are placed end to end to produce an obstacle that must be at least 30 feet (9 m) wide. Each hurdle section consists of two uprights with pointed legs that are driven into the ground and five horizontal rails, between which is interwoven birch or another suitable material. Gorse, which is durable but has sharp thorns, is not permitted. The hurdles must be driven into the ground at an angle of 62 degrees so that the top bar is set back 20 inches (51 cm) from the vertical, and the effective height of the hurdle is 37 inches (94 cm). All of the exposed timber parts must be padded with a minimum of  inch (1.3 cm) of high-density polyethylene or closed cell foam rubber (Figure 112-1).

inch (1.3 cm) of high-density polyethylene or closed cell foam rubber (Figure 112-1).

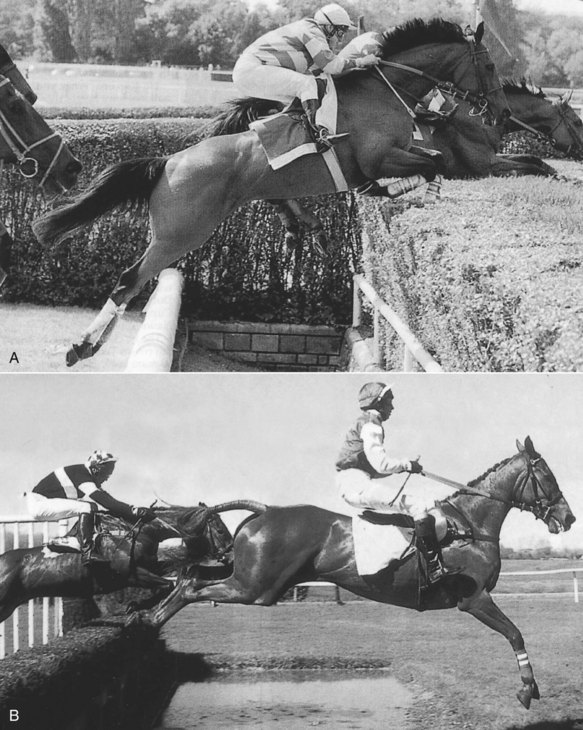

Steeplechases are run from 2 to  miles (3 to 7 km) over fences that, with the exception of those at Aintree, over which the Grand National is held, have a standard construction. The course must have at least six fences per mile, one of which must be an open ditch, with the other plain fences. The plain fences must be a minimum of 54 inches high (1.37 m) and constructed of birch, or birch and spruce, in a frame. The use of gorse is not permitted. The base of the fence must be 72 inches (1.83 m) from front to back, with the thickness of the fence at its top not less than 18 inches (46 cm) (Figure 112-2, A). Plain fences usually have a guard rail on the face of the fence that usually is padded with the same material as the hurdles. An open ditch has similar overall dimensions, but the ditch in front of the fence, which may or may not be dug out, must be at least 72 inches (183 cm) from front to back and be delineated by a takeoff board that is up to 24 inches high (146 cm). Designers of racecourses also, if they wish, may include a water jump in steeplechases. These consist of a smaller fence, up to 36 inches (91 cm) high, with a 108-inch (2.74-m)–wide water ditch, which must be 3 inches (7.6 cm) deep, on the landing side of the fence.

miles (3 to 7 km) over fences that, with the exception of those at Aintree, over which the Grand National is held, have a standard construction. The course must have at least six fences per mile, one of which must be an open ditch, with the other plain fences. The plain fences must be a minimum of 54 inches high (1.37 m) and constructed of birch, or birch and spruce, in a frame. The use of gorse is not permitted. The base of the fence must be 72 inches (1.83 m) from front to back, with the thickness of the fence at its top not less than 18 inches (46 cm) (Figure 112-2, A). Plain fences usually have a guard rail on the face of the fence that usually is padded with the same material as the hurdles. An open ditch has similar overall dimensions, but the ditch in front of the fence, which may or may not be dug out, must be at least 72 inches (183 cm) from front to back and be delineated by a takeoff board that is up to 24 inches high (146 cm). Designers of racecourses also, if they wish, may include a water jump in steeplechases. These consist of a smaller fence, up to 36 inches (91 cm) high, with a 108-inch (2.74-m)–wide water ditch, which must be 3 inches (7.6 cm) deep, on the landing side of the fence.

Point to point races (see Figure 112-2, B), named because originally they were run from one point to another, represent the amateur branch of steeplechasing and are restricted to horses that have qualified to race by hunting with a registered pack of hounds. Races for such horses also take place on licensed racecourses and are known as Hunters’ Steeplechases (or Hunter chases).

Some races, notably in France, at Punchestown in Ireland, and at Cheltenham in Britain, are run over more natural obstacles, including banks and growing hedges. Timber races are held over upright (United States) or sloping (Britain) post and rail fences (Figure 112-3). To make the obstacles less dangerous, the top rails may be sawn through so that they will knock down if they are hit hard.

Racing National Hunt Horses

Because of the two distinct sources of horses that enter National Hunt racing, a wide variety of injuries is seen, ranging from injuries related to beginning training to degenerative injuries associated with overuse. In addition to the injuries sustained while the horse is in training, a National Hunt horse is more prone to injury after a fall than is a flat racehorse (Figure 112-4). It is also important to be aware that horses that are skeletally mature when they begin training (4- to 5-year-old store horses) still undergo the same pathophysiological processes that lead to stress fractures, albeit in different sites from the 2- or 3-year-old Thoroughbred. Because National Hunt racing continues throughout the year, the going under foot (footing) can vary, and extremes of both soft and firm going place the National Hunt horse under extra stress from injury.

Track Surface or Training Surface and Lameness

The influence of falls on the nature of injuries is substantial.2-7 Most falls occur on landing over a fence. Falls may result from the horse or jockey making a jumping error, from interference by another horse still in the race, or from a loose horse that had previously unseated its rider. The fall of one horse may result in the fall of one or more other horses (Figure 112-5). Thus injuries may result from the fall and impact with other horses. Falls may result in fatal fractures of the cervical or thoracolumbar vertebrae. Rib fractures usually result from a fall and may cause severe lameness and/or respiratory signs. Other fractures seen commonly, usually resulting from a fall, include scapular, radial, and humeral fractures; fractures of the accessory carpal bone; and fractures of the lateral malleolus of the tibia. Major muscle ruptures, especially in the hindlimbs (e.g., semimembranosus, quadriceps, or adductor) also usually result from a fall. Rupture of the fibularis tertius may occur if the horse falls with forced hyperextension of the hock.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

miles (7.2 km).

miles (7.2 km).