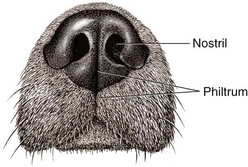

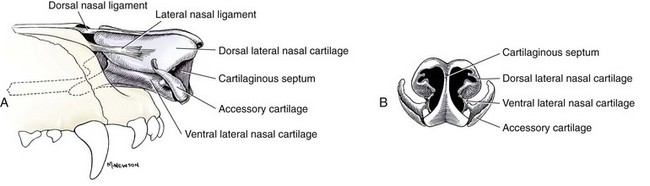

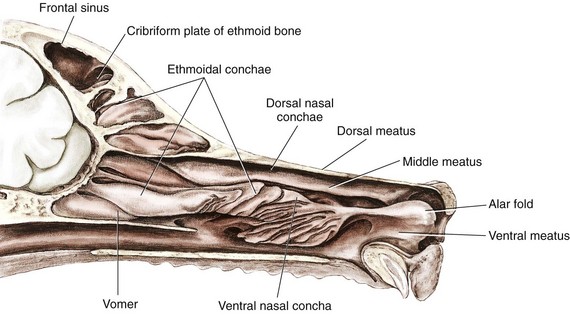

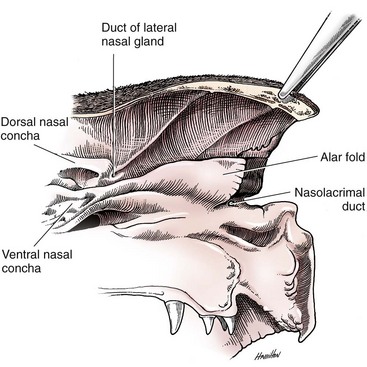

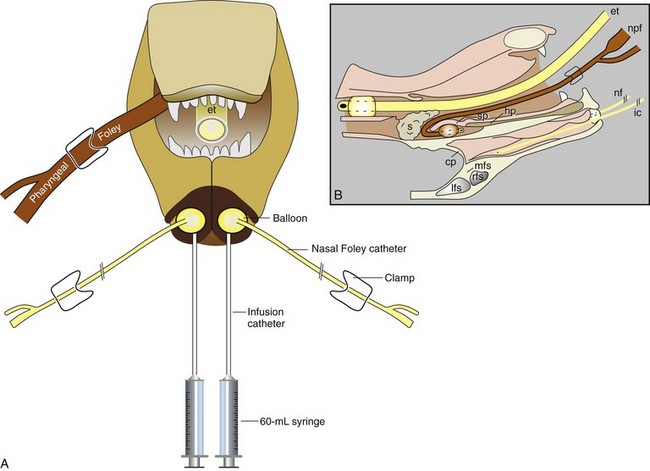

Chapter 99 The nasal cavity begins at the nostril, ends at the choanae, and is divided longitudinally by the nasal septum into two nasal fossae. The nasal planum is the pigmented, hairless, rostralmost surface of the external nose. The philtrum is the midsagittal external crease in the nasal planum. The nasal openings are referred to as nares or nostrils and open into the nasal vestibule (Figure 99-1).46,76 The external nose is supported by a paired, symmetric, cartilaginous frame (Figure 99-2). The cartilaginous septum separates the right and left nasal fossae in the rostral midsagittal plane. Caudally, this cartilaginous division becomes a bony septum. The paired dorsolateral nasal cartilages support and shape the wings of the nostrils (also called the ala nasi). The ventral lateral nasal cartilages are continuous with the septal cartilages and form the floor and the lateral wall of the nasal vestibule. The accessory nasal cartilages create the ventral aspect of the midlateral slit in the nose (just beneath the wings of the nostrils). Within the nasal cavity, the dorsal and larger ventral conchae define the air passages. These air passages are named the dorsal, middle, ventral, and common nasal meatus based on their location (Figure 99-3). Rostrally, the alar fold is a bulbous extension of the ventral nasal conchae that fuses with the wing of the nostril (Figure 99-4). In the caudal and ventral nasal cavity, the ethmoidal labyrinth is formed by scrolls of ethmoidal conchae, which are outgrowths of the ethmoid bone. There are three paranasal sinuses: the maxillary recess, sphenoidal sinus, and frontal sinus. The maxillary recess is in the lateral aspect of the nasal fossa approximately at the level of the last premolar and first molar. The sphenoid sinus lies within the presphenoid bone and houses a portion of the ethmoidal conchae. The frontal sinuses are the most commonly encountered sinuses from a surgical perspective and are divided into rostral, medial, and lateral compartments. The size and specific anatomy of the frontal and sphenoid sinuses can be variable, and these sinuses may be absent in some animals.148,160 The frontal sinuses are connected to the nasal fossa via the nasofrontal opening, through which an ethmoidal turbinate extends. The nasopharynx is the portion of the pharynx dorsal to the hard and soft palates.46 The choanae are the rostral nasopharyngeal meatus; they are considered the caudal border of the nasal cavity. At this location, the ventral, dorsal, and lateral walls of the nasopharynx are formed by the hard palate, vomer bone, and palatine bone, respectively. Each auditory tube opens into the lateral nasopharynx through a slitlike opening directly caudal to the caudal border of the pterygoid bone. At rest, dogs and cats breathe through their noses. Inhaled air is warmed and humidified by the rostral portions of the nasal mucosa, and the mucosa itself is cooled by this interaction. At exercise or with high ambient temperature, dilatation of blood vessels that comprise the rich vascular supply to the nasal mucosa enhances heat and moisture exchange. At extremes of exertion or temperature, dogs and, to a lesser extent, cats change to mouth breathing (panting) to exaggerate evaporative cooling even further by use of the larger surface area of oral mucosa.58,163 The caudodorsal portions of the nasal mucosa are primarily dedicated to olfaction, and dogs in particular can be observed to sniff rapidly rather than inhale normally when engaged in hunting. This staccato inflow of air at high speeds is thought to cause turbulence in the nasal cavity that directs air into the dorsal meatus and creates a constant influx of new scent information.163,166 The moist appearance of the nasal planum in healthy dogs is primarily a function of secretions from the paired lateral nasal glands. The precise stimulus for and function of these secretions are not known. The rate of secretion increases in warm climate conditions and in dogs tempted with food, suggesting physiologic and psychologic cues and a role in evaporative cooling. The serous fluid also contains IgA, which suggests a defensive function. The lateral nasal glands of cats are smaller, and their secretion is less copious and more mucoid.1,163 The exact functions of the paranasal sinuses in dogs and cats are unknown. Possible functions may include additional warming or humidification of inhaled air, immunologic activities, vocal resonance, and contributions to facial shape. In humans, the frontal sinuses have been shown to produce significant amounts of nitric oxide, which may have an antimicrobial effect.110 Historical and Physical Examination Findings Dogs and cats with nasal or nasopharyngeal disease typically present for signs of nasal discharge, sneezing, reverse sneezing, stertorous respiration (inspiratory snoring), or epistaxis. In cats, stertorous respirations and phonation changes are more commonly associated with nasopharyngeal disease, but cats with nasal disease alone exhibit sneezing and nasal discharge. Stertor may be less evident in dogs with nasopharyngeal disease because dogs readily relieve turbulent airflow by panting, which cats seldom do.5,74,81 Nasal discharge varies in its consistency, color, and localization, and its description is weakly correlated with the final diagnosis. Some authors find that epistaxis or unilateral discharge is more suggestive of a final diagnosis of neoplasia, but other studies fail to document this relationship.* In cats, ocular discharge may be seen concurrently with nasal discharge, and in either species, external nasal deformity is occasionally seen or palpated.39,96,154,182 Airflow may be reduced or absent from one or both nares, suggesting complete obstruction of the nasal passage by a mass or fluid.33 Oral examination in patients with clinical signs suggestive of nasal disease may identify a pharyngeal mass; deviation, erosion, or ulceration of the hard or soft palate; or dental disease. Thorough oral examination is commonly postponed until the animal is sedated or anesthetized for other diagnostic procedures. General physical examination may also reveal enlarged regional lymph nodes, which can subsequently be aspirated as part of the diagnostic plan.5,81 For dogs and cats, the major differential diagnoses for historical and physical examination findings described above include neoplasia (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, lymphoma and others), inflammatory polyp, fungal infection, viral infection, bacterial infection (which is commonly secondary to an underlying problem), foreign body, dental disease, and idiopathic rhinosinusitis.* In dogs and cats, the relative prevalence of each disease has been variably reported, and historical and clinical features are highly overlapping. Imaging or endoscopy with histopathology is typically required to achieve a definitive diagnosis.39,152,158,167 The signalment may be suggestive with some conditions. For instance, nasal aspergillosis is overrepresented in larger breed dogs compared with smaller breeds.153 Inflammatory polyps are classically associated with younger cats; however, a recent report documented an average age of 5 years at the time clinical signs developed, and cats as old as 10 years have been diagnosed with this condition.74,180 Radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly used to evaluate nasal disease in dogs and cats. Similar to all skull radiographs, nasal radiographs must be performed under general anesthesia to enable patient positioning. To avoid superimposition of the mandible, intraoral dorsoventral and open-mouth ventrodorsal projections are commonly used. The open-mouth ventrodorsal view has the advantage of allowing visualization of the cribriform plate. The frontal sinuses can be individually evaluated in the rostrocaudal frontal sinus projection.144,172 As cross-sectional imaging modalities become increasingly available, clinicians are performing fewer radiographic studies in patients with nasal symptoms. Properly performed radiographs can still be an important part of the investigation. In recent retrospective studies of dogs and cats, the radiographic criterion with greatest predictive value for diagnosis of nasal neoplasia was destruction of surrounding bones (lacrimal, palatine, and maxillary). An increasing severity of bone lysis was associated with a greater likelihood of neoplastic disease. Radiographic signs consistent with a diagnosis of rhinitis were a lack of frontal sinus lesions and a lack of lucent foci in the nasal cavity. Factors that were not strong predictors of any diagnosis included the location of lesions within the nose; involvement of teeth; unilateral or bilateral distribution of lesions; and, in cats, septal deviation or lysis.† Cross-sectional imaging provides more detailed information about the nose’s complex architecture and may be better able to differentiate rhinitis from neoplasia. CT has been widely used for this purpose, and MRI is also increasingly available. If radiation therapy is planned for nasal neoplasia, the use of CT assists with accurate treatment planning.172 In one of the original studies to investigate CT imaging of the nose, CT was found to be superior to radiography for detecting changes associated with nasal neoplasia in 21 dogs with confirmed nasal neoplasia.136 Findings characteristic of nasal disease discovered on cross-sectional imaging are essentially similar to those described for nasal radiography, although more subtle lesions may be detected. Intranasal mass lesions on CT or MRI are typically seen with fungal rhinitis or nasal neoplasia in dogs, and masses associated with fungal rhinitis may have a characteristic cavitary apppearance.153,155 Dogs with a final diagnosis of inflammatory rhinitis may also have an apparent mass on cross-sectional imaging, but often this mass fails to enhance in postcontrast imaging sequences.119 Intranasal masses and vomer or paranasal bone lysis are seen in dogs and cats with neoplastic nasal disease.119,158 The presence of nondestructive, bilateral nasal mucosal thickening and fluid accumulation is associated with a final diagnosis of inflammatory rhinitis.27,119,158,177 Additionally, a recent study documented that up to 28% of cats with inflammatory rhinitis also demonstrate bulla effusion in the absence of otitis externa.40,155 Septal deviation and sinus asymmetry can be part of the range of normal for the feline skull; these variations must not be interpreted as disease when documented on cross-sectional imaging.148 Although septal lysis or cribriform lysis is predictive of a neoplastic diagnosis in dogs, the significance of these findings is debated in cats.131,148,158,177 Endoscopy allows direct observation of the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and occasionally the sinuses and facilitates collection of directed samples. The nasopharynx and choanae are observed by retroflexion of a flexible endoscope or by use of a spay hook to retract the soft palate and a dental mirror to examine the area. Nasal passages are evaluated by rigid or flexible rhinoscopy. Techniques and equipment for this procedure are thoroughly described elsewhere.29,64,128 Most clinicians perform retroflexed choanal and nasopharyngeal endoscopic examination before the rhinoscopic examination to avoid obscuring observation of the choanae and nasopharynx by blood, mucus, or flush.186 A recent retrospective study of 115 dogs and cats confirmed that the retroflexed choanal view provided diagnostic information and therapeutic access that would not have been provided by rhinoscopy alone. In this study, 36 animals had masses visible on retroflexed choanal examination that were not seen, and therefore could not have been biopsied, from a rhinoscopic approach.186 Directed biopsy collection via this approach typically yields diagnostic material.38,108,186 The retroflexed choanal approach may also enable observation and retrieval of nasopharyngeal foreign bodies that are not accessible by other means.179,186 Rhinoscopy commonly reveals nasal discharge and hyperemic mucosa, although neither the presence nor the severity of mucosal abnormalities seen on rhinoscopy predicts the presence or severity of histopathologic abnormalities.83 In dogs, rhinoscopy may enable visual identification of tumors or fungal granulomas, although this may be less rewarding in cats.83 Nasal tumors typically appear as obstructive grey to white soft tissue masses with a reflective surface and bleed easily upon contact with the rhinoscope or with biopsy.33 Material for diagnostic submission can be collected by swab, flush, or biopsy. Discrete lesions should be sampled directly, but the nasal mucosa should be sampled bilaterally even if no focal lesion is seen.* Material for cytologic evaluation may be collected by flush, swab, brush, fine-needle aspirate, or imprint from a biopsy sample. The accuracy of cytology results to predict biopsy or necropsy results is variably reported; therefore, cytology should be considered only a preliminary or screening test in most cases.† Because many patients with rhinitis have persistent inflammation, cytology samples may overrepresent the neutrophilic component of the disease by providing only superficial material.190 Some types of neoplasia do not exfoliate well with cytologic sampling techniques and therefore may not provide diagnostic material, although cytology of imprints from biopsy samples has been shown to provide greater sensitivity for the diagnosis of neoplasia than brush cytology of the mass itself.23,90 For these reasons, cytology is generally considered to be more sensitive than specific, meaning that a cytologic diagnosis is likely correct, but potentially incomplete, information.118 If imaging or endoscopic findings are suggestive of fungal disease, hyphae will usually be detected on cytologic or histopathologic evaluation; however, material should be reserved in case culture becomes necessary. Antigen serology for Cryptococcus spp. in cats is highly sensitive and specific and may eliminate the need for invasive diagnostics.62 Routine bacterial culture is seldom informative in nasal disease because the nose has normal bacterial flora and because any underlying disease causing turbulent airflow favors opportunistic infection. However, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for specific bacteria may be helpful and is commonly performed. Mycoplasma and Bartonella spp. have been suggested as causes of chronic rhinitis in dogs and cats, although recent PCR-based studies have failed to document either agent as a common cause.71,191 Serology for Bartonella antibodies and PCR for detection of Chlamydophila spp., canine adenovirus-2, and parainfluenza virus-3 in canine chronic rhinitis have also failed to detect these organisms.71,191 A nonspecific PCR for fungal nucleic acids did detect higher levels of fungal DNA in dogs with inflammatory rhinitis compared with dogs with nasal cancer. The significance of this finding is unclear and could reflect trapping of environmental fungal elements in nasal secretions or a causative role for fungi in the perpetuation of chronic rhinitis.191 The nasal planum is affected by numerous pathologies. Clinically, animals may present with ulceration, nasal discharge, a mass lesion, or depigmentation. Depigmentation is a frequent result of several conditions of the nasal planum or may be idiopathic.183 Many distinct diseases of the nasal planum manifest with grossly similar lesions, so a biopsy is frequently required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Several congenital or acquired medically managed conditions of the nasal planum have been described. Hereditary nasal parakeratosis has been described in Labrador retrievers.141 Autoimmune disease such as discoid lupus erythematosus, systemic lupus erythematosus, pemphigus complex, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada-like syndrome may have nasal planum lesions.183,185 Idiopathic depigmentation, or vitiligo, has been diagnosed in Rottweilers and Doberman Pinscher dogs and may also be associated with uveitis and uveodermatologic syndrome.88,159,161,183 Animals with little pigmentation and high exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation are at risk for actinic dermatitis, which may progress to squamous cell carcinoma.59 Dermal arteritis has been reported in a limited number of dogs as a chronic, solitary circular ulcer specifically affecting the nasal planum.145,174 Mucocutaneous pyoderma may also occur on the nasal planum and appear very similar to discoid lupus in clinical presentation and histopathology.185 Other less common lesions on the nasal planum may result from allergic contact dermatitis, usually from plastic food bowls; vasculitis–cold agglutinin disease; idiopathic sterile granuloma formation (“clown-nose”); cutaneous histiocytosis; or lentigo. The most common surgically addressed disease of the nasal planum is neoplasia. Neoplasia of the nasal planum is more common in cats than dogs, and squamous cell carcinoma is thought to be the most common form of neoplasia arising on the nasal planum.36,192 Other tumors reported in this location include lymphoma,123 malignant histiocytosis,122 fibrosarcoma,93,101 malignant melanoma,193 lymphomatoid granulomatosi,193 basal cell carcinoma,193 fibroma,36 mast cell tumor,53 hemangiomas, hemangiosarcoma,115 and eosinophilic granulomas.37 Squamous cell carcinoma is a locally invasive malignancy that invades adjoining soft tissue and bone. As in humans, exposure to sunlight likely plays a role in the malignant transformation of normal squamous epithelial cells in dogs and cats.45,59 Papillomavirus may also play a role in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma.124,125 Classically, older white cats appear at risk for developing this tumor in areas of the body subject to high solar radiation exposure, including the nasal planum.41,59 Evidence suggests that solar radiation also plays a role in the pathogenesis of cutaneous hemangioma and hemangiosarcoma in dogs.67 Because of the risks associated with excessive sun exposure, client education is warranted, especially if the pet is of lighter color or is frequently outdoors. Complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice for squamous cell carcinoma. Survival times after surgical treatment have been reported in several small case series. Median survival times of 12.5 weeks (range, 6 to 19; n = 6) with surgery alone to 26 weeks (range, 1 to 26; n = 4) with radiotherapy alone were reported in dogs with squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal planum.102 Using data extrapolated from a series of eight cats treated for squamous cell carcinoma, the median survival time was 12 months (range, 1 to 20).193 Survival times are short because these tumors can be quite invasive and obtaining adequate surgical margins, especially in cats, is difficult. Local recurrence was noted in 12 of 17 dogs after various therapies102 and in three of eight cats193 after nasal planum resection. Because complete excision is difficult and local recurrence is common, adjuvant treatment therapies may be required. Cryotherapy and external-beam radiotherapy are reported treatment modalities for nasal planum squamous cell carcinoma.36,97,102 Photodynamic therapy, proton irradiation, strontium-90 plesiotherapy, and intratumoral administration of carboplatin have also been reported as primary or adjuvant treatments with some success, particularly in animals with small, superficial lesions.16,47,61,66,170 Stenotic nares are encountered most commonly as a component of brachycephalic syndrome in dogs.* English bulldogs, pugs, Boston terriers, Pekingese, and Cavalier King Charles spaniels are the most frequently reported breeds.109,150,175 Although less common, brachycephalic feline breeds, especially Persians and Himalayans, may also experience stenotic nares.70,74 Dogs with stenotic nares experience obliteration of the nares because of axial deviation of the dorsolateral nasal cartilage and the associated epithelium and mucosa (wing of the nostril). This results in significant upper airway obstruction and is theorized to precede and instigate other components of brachycephalic airway syndrome.8 Significant negative pressure must be created in the lumen of the lower airways and larynx to overcome the upper airway obstruction and move adequate volumes of air for ventilation. This substantial negative intraluminal pressure results in supraphysiologic stress on the laryngeal and tracheal soft tissue and cartilage. Relatively quickly, these forces result in tissue edema, collapse of laryngeal cartilages, and further obstruction of airflow. Surgical correction of stenotic nares can significantly reduce upper airway obstruction and can be performed at a very early age to prevent progression of other components of brachycephalic airway syndrome, including laryngeal collapse.80,142 In addition to axial displacement of the dorsolateral nasal cartilage, intranasal stenosis or airway obstruction from abnormal conchal development may also play a significant role in upper airway obstruction associated with brachycephalic syndrome.132–134 Using cross-sectional imaging of the nose of brachycephalic dogs with upper airway obstruction, investigators identified abnormal conchae in all brachycephalic dogs they evaluated.134 Aberrant conchae either arose rostrally or caudally and tended to have abnormal branching and crude lamellae.134 In another study, 11 of 53 brachycephalic dogs and two of 10 brachycephalic cats had nasopharyngeal turbinates identified during rhinoscopy.55 Of the 11 dogs with nasopharyngeal turbinates, nine (82%) were pugs. These studies suggest that abnormal turbinates play a role in occlusion of nasal passages and compound upper airway obstruction in brachycephalic breeds. Neoplasia is a common cause of nasal and nasopharyngeal disease of small animals and is reported in 15% to 54% of dogs and 29% to 70% of cats with chronic nasal symptoms.* Although history, physical examination, and imaging findings are similar among nasal diseases, unilateral hemorrhagic discharge with aggressive lytic lesions and extension outside the nasal cavity may be suggestive of neoplasia.74,96 Some authors believe that extension into the frontal sinus, in particular, supports a diagnosis of neoplasia; other studies have failed to confirm this finding.152,189 In cats, lymphoma is generally reported to be the most common form of nasal neoplasia.5,30,38,74,81 It is commonly confined to the nose and nasopharynx; however, a recent study suggested that up to 45% of cats may have multiorgan involvement.108 When treated with multiagent chemotherapy, the median survival time was 98 days.74 Other neoplasms diagnosed in the feline nose include adenocarcinoma (reported as more prevalent than lymphoma in one study96), squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, and unspecified sarcoma.5,38,74,96 In dogs, nasal neoplasia is nearly always malignant, and adenocarcinoma is the most common tumor type.4,33,81 The average age at diagnosis is approximately 10 years, and medium to large breeds appear to be overrepresented.4,167,194 Despite the locally aggressive nature of nasal neoplasia in dogs, the rate of metastasis is low; when metastasis occurs, it is usually to the regional lymph nodes and lungs.2,116 Although chemotherapy has been shown to have some efficacy in dogs with nasal tumors,100 cytoreductive surgery has not been shown to improve survival in dogs with intranasal neoplasia.75,116 Radiation therapy is therefore recommended as the treatment of choice in patients with intranasal neoplasia. After curative-intent radiation therapy with or without cytoreductive surgery, median survival times range from 8 to 19 months.2,75,95,116,169 In another study, dogs with nasal exenteration after radiation therapy had significantly longer survival times compared with dogs that underwent radiation therapy alone.4 Complications were increased, however, in the group of dogs that underwent surgery after radiation therapy.4 Dogs with less severe disease (e.g., unilateral involvement and no bony lysis beyond the nasal turbinates) that were treated with curative-intent radiotherapy had longer median survival times (23.4 months); dogs with involvement of the cribriform plate had shorter median survival times (6.7 months).4 Palliative radiation therapy may also be an option in these patients. In a study of 48 dogs receiving coarse-fraction palliative radiation therapy, 66% had resolution of clinical signs for a median of 120 days.52 The overall median survival time in that study was 146 days.54 Staging scheme revisions performed in attempt to refine prognostic indicators have not clarified additional predictive features of the disease.4,52,94,194 A wider variety of tumor types is reported in dogs compared with cats, including carcinoma (adenocarcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, anaplastic, transitional cell), sarcoma (chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, spindle cell sarcoma, and undifferentiated sarcoma) and round cell tumors (lymphoma, mast cell tumor, transmissible venereal tumor), as well as rare reports of benign neoplasia (e.g., pleomorphic adenoma and oncocytoma).33,81,117,186 Some have suggested that sarcomas in dogs are associated with a better prognosis than carcinomas,169 particularly when considering undifferentiated anaplastic and squamous varieties.2,4,194 This has not been consistently shown in other studies.3,95,116 Feline upper respiratory tract infection complex consists of herpesvirus, calicivirus, Chlamydophila spp., Mycoplasma spp., Bordetella spp., and others and is probably the most common cause of sneezing and oculonasal discharge in young to adult cats. These symptoms are commonly self-limiting or respond to supportive care in the form of rest, warm steam therapy, and tempting foods.62,73,147,171 Canine upper respiratory tract infection complex, caused by canine adenovirus-2, parainfluenza virus, Bordetella spp., Mycoplasma spp., and others is typically a cause of coughing rather than nasal discharge and is also usually self-limiting.26,62 Although it is theorized that frequent or persistent infection with these agents may lead to chronic idiopathic rhinitis (described below), this association has not been proven, and no therapy has been shown effective in prevention of the chronic form.71,74,191 Bacterial flora are present in the noses of both species and are not currently believed to be causative of disease, although they may flourish as opportunists when other nasal pathology exists. The most common fungal pathogen of the nose of dogs is Aspergillus fumigatus; Blastomyces dermatidis and Pythium insidiosum are occasionally reported. Nasal aspergillosis is most common in young, large-breed dogs and causes a destructive rhinitis, which can be difficult to distinguish from nasal neoplasia on radiography, CT, or MRI.81,117,167 The most typical radiographic appearance is conchal lysis and punctate bony lucency with soft tissue opacity contents or a mass in the nose and sinuses. In advanced cases, nasal septum deviation or erosion can be seen, and rare cases can invade locally into the orbit.119,153,172,187 Although a substantial proportion of dogs with Aspergillus fungal rhinitis develop fungal sinusitis as well, a review of CT findings failed to identify any dog with fungal sinusitis in the absence of nasal involvement.153 In cats, Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common nasal fungal infection and causes persistent nasal discharge and sneezing, typically without systemic signs.62 Nasal, sinus, and retrobulbar infection by P. insidiosum, A. fumigatus, and various opportunistic fungi have been reported in rare instances in cats and cause similar destructive rhinitis as described for dogs.10,19,87 A. fumigatus is the most common cause of fungal rhinosinusitis in dogs. This locally invasive infection occurs as plaquelike lesions within the air spaces of the nasal cavity. For this reason, systemic antifungal therapy does not achieve adequate penetration to eradicate the infection, and a variety of topical therapies have been developed.62 The original therapy for fungal rhinitis involved trephination of the sinuses and nasal cavity for placement of catheters and infusion of either low-dose enilconazole daily for 7 to 10 days or high-dose clotrimazole once under anesthesia. This approach was highly invasive and, unless the transverse septum separating the lateral and the rostral portions of the frontal sinus was penetrated at the time of trephination, the medication did not readily reach the rostral portion.149 Subsequently, a noninvasive technique was developed that involved occlusion of the nasopharynx and nares and placement of infusion catheters into the nasal cavity via the nares (Figure 99-5). This technique provided distribution of infusate into all parts of the nasal cavity and sinuses.113,149 Studies have shown that the majority of dogs (65%) treated by either surgically placed or noninvasively placed infusion catheters are cured after the first infusion; overall, 87% of dogs are cured with repeated (up to four) infusions.62,114,165 Most clinicians use resolution of clinical signs to determine whether repeated infusion is indicated, although rhinoscopic recheck has been recommended by some authors.196 Although the CT finding of soft tissue opacity associated with fungal rhinosinusitis decreases with effective therapy, this decrease has not proven to be quantifiable as a predictor of the need for repeated treatment.153 Given the improved infusate distribution, limited side effects, lessened discomfort, and comparable treatment success for noninvasively placed catheters, this technique has now supplanted surgical catheter placement for the treatment of fungal rhinitis in dogs in the United States. Many of the readily commercially available preparations of clotrimazole in Europe contain propylene glycol or isopropanol; both are irritating to the mucosa. Investigators have researched enilconazole (1% or 2% suspension) as an alternative. Using the catheter placement technique described by Richardson and Mathews,149 with or without rhinoscopically guided placement of the infusion catheters directly into the frontal sinuses, the majority of dogs treated with enilconazole achieved a cure within two treatments.196 For refractory cases, use of povidone-iodine packing or enilconazole irrigation though an open rhinotomy has also been described. Purported advantages of rhinotomy or sinusotomy include visual inspection of healing tissues, physical application of topical antimicrobial to lesions to ensure complete coverage and potentially decrease the quantity of medication needed, continued opportunity for debridement, alteration of the intranasal environment, and relatively simple delayed closure when the infection is cured.140 Highly invasive procedures should be reserved for unusually difficult cases and are not necessary for routine fungal rhinitis.31,121 Although cryptococcal rhinosinusitis is far more common in cats, infection with Aspergillus spp. does occur and should be treated by clotrimazole infusion via noninvasively placed catheters.173 Foreign bodies found in the noses of dogs and cats commonly include plant matter; however, a wide variety of items may be found. Radiographic findings in the case of nasal foreign bodies are nonspecific, only suggesting rhinitis. Occasionally, a radiopaque foreign body itself may be visualized.172,179 The retroflexed choanal view may be useful to diagnose and retrieve intranasal or nasopharyngeal foreign bodies or to flush the nose copiously when a foreign body is suspected but cannot be located or visualized. In some instances, this does produce the foreign material.74,81,93,186 In dogs and cats, extensive investigation commonly fails to reveal a cause of nasal disease. Depending on the report, up to 49% of dogs and 65% of cats may be diagnosed with “inflammatory rhinitis,” “lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis,” or “idiopathic rhinitis.” Such histologic diagnoses confirm inflammation is present; however, the inciting cause of the inflammation is not known.74,81,117,119,167,177 Imaging studies of affected animals typically reveal increased soft tissue opacity within the nasal cavity, with or without lysis of conchae, but lysis of other bones is not seen.119,131,152,155,172 Soft tissue opacification consistent with fluid accumulation may also be observed in the sinuses by radiography or CT.136 Surgical ablation of the nasal turbinates or inclusion of the nose within the field of external-beam radiation therapy may cause a similar clinical syndrome.194

Nasal Planum, Nasal Cavity, and Sinuses

Anatomy

Nasopharynx

Physiology

Diagnostic Approach

Imaging

Rhinoscopy and Nasopharyngoscopy

Sample Submission

Diseases of the Nasal Planum

Neoplasia of the Nasal Planum and Nasal Planum Resection

Diseases of the Nose and Sinuses

Neoplasia

Infection

Treatment of Fungal Rhinosinusitis

Foreign Bodies

Idiopathic Inflammatory Rhinitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree