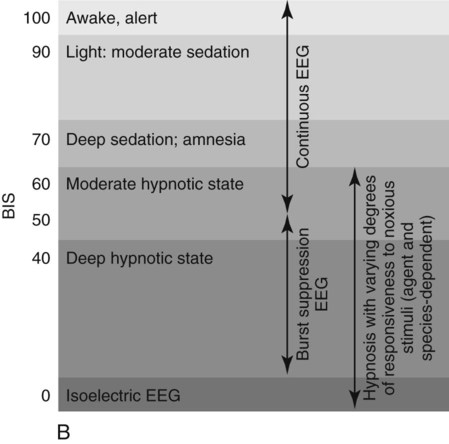

I The animal’s ability to compensate for anesthetic induced changes are generally depressed by anesthesia II Perioperative monitoring is a sentinel for abnormal or deteriorating physiology and improves safety during anesthesia: A Frequent monitoring of physiologic variables facilitates informed and timely responses to changes in the animal’s status B The completion of an anesthetic record provides method to objectively trend changes and a database for comparison with subsequent anesthetic procedures III Prerequisites for helpful intraoperative monitoring: A trained vigilant anesthetist is the most important. This means: A Applied understanding of normal physiology and pathophysiology B Thorough, accurate knowledge of the animal’s history and physiologic status C Knowledge of the pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicity of anesthetic drugs and perioperative therapies D Availability of a convenient system for recording observations (anesthetic record) E A thorough knowledge of the monitoring devices, their operation and limitations, and the inherent assumptions associated with their use I Monitor body functions (see Chapter 2 for normal values) A Formulate a monitoring plan based on the following: 1. Animal’s health status and disease(s) 2. Specific procedure to be performed 3. Anesthetic drugs and techniques selected 4. Available monitoring equipment B Intraoperative decisions are based on comparisons with normal values (i.e., Are observed responses to anesthesia qualitatively and/or quantitatively appropriate? Are measured variables within normal limits?) II Monitor more than one body system and more than one variable per body system, when possible A Evaluating several indices over time (e.g., heart rate, respiratory rate) rather than fragments of information increases the likelihood of detecting abnormal responses to anesthesia B Determining trends in individual variables facilitates an early diagnosis and response III Use monitoring techniques that are specific, accurate, and complementary I Information is gathered by observing readily apparent variables (e.g., rate of volume of breathing) and/or employing diagnostic testing (e.g., ECG; pulse oximeter; ABP; capnometry (ETCO2]; transcutaneous (O2, CO2) that does not invade the body 1. Devices are generally easy to use, reasonably reliable, and can be used to determine trends or changes in the monitored variable 2. Animal is not at risk for complications caused by the monitoring technique 1. Not all physiologic variables (e.g., pH and blood gases, electrolytes, lactate) can be accurately monitored noninvasively 2. Inaccurate (highly variable) information is sometimes gathered when a noninvasive technique (e.g., noninvasive ABP) is substituted for a more invasive procedure (e.g., arterial catheterization) to determine the same information I Information is gathered by placing instruments within the body (e.g., intravascular pressure catheters, tissue oximetry, temperature) 1. Data is less influenced by confounding factors 2. Many accurate, reliable, and simple monitoring techniques are available 3. A direct measurement of a physiologic variable is often provided with fewer assumptions II Monitoring key organ systems: Classic monitoring signs were described in terms of stages and planes of anesthesia. These classic signs use eye position and reaction, muscle relaxation, respiratory rate and pattern, and response to surgical stimulation to determine anesthetic depth (see Fig. 9-1). The signs of anesthesia were developed based on diethyl ether anesthesia but continue to be useful for describing the depressant qualities of anesthesia. A Central nervous system (CNS) 1. Observe reflex activity to monitor degree of CNS depression a. Eye reflexes: Generally more useful and discriminative in large animals (1) Palpebral: brisk if too light, absent in many animals, and when the animal is in a surgical plane of anesthesia (2) Corneal: lightly touch the cornea with gauze or cotton. Present until the animal is deeply anesthetized. (3) Nystagmus: present during light planes of anesthesia (4) Lacrimation: often present with nystagmus, indicating light plane of anesthesia b. Jaw tone: an indication of overall muscle relaxation. Moderate resistance to fully opening the mouth is present during a moderate surgical plane of anesthesia. More useful in small animals. c. Anal reflex: dull to absent during a surgical plane of anesthesia (species dependent) d. Pedal reflex: absent with toe pinch during a surgical plane of anesthesia. Withdrawal indicates a light stage of anesthetic that is likely to be inadequate to perform surgery. 2. Monitor skeletal muscle tone and degree of relaxation a. Records and averages brain activity b. Correlates to depth of anesthesia 4. End-tidal concentration of anesthetic gases can be monitored, correlated to anesthetic depth, and compared to known MAC values for a particular inhalant anesthetic (see Fig. 14-2, A, and B) B Ventilation and the respiratory system (see Boxes 14-1 and 14-2; Figs. 14-3 through 14-8)

Monitoring During Anesthesia

Overview

General Considerations

Basic Principles

Noninvasive Monitoring Techniques

Invasive Monitoring Technique

Physiologic Considerations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree