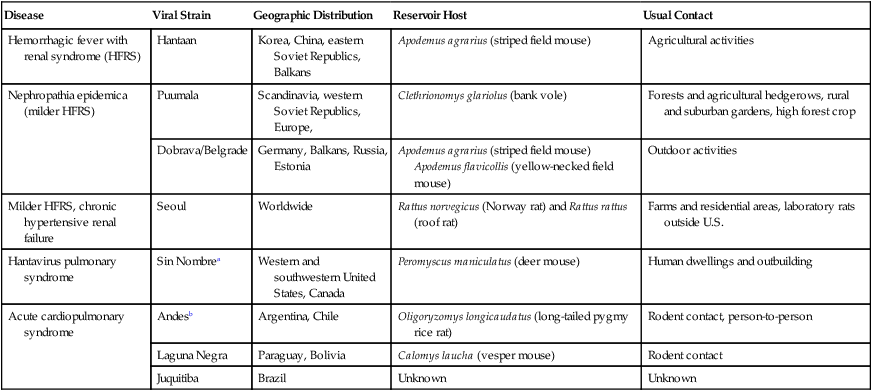

Craig E. Greene and Bruno B. Chomel Hantaviruses are enveloped spherical RNA viruses in the family Bunyaviridae, which contains three other major genera that can be distinguished genetically, morphologically, and antigenically. Unlike other members of the Bunyaviridae, transmission of hantaviruses does not require arthropod vectors (for comparison, see Bunyaviridae, Chapter 24, Arthropod-Borne Viral Infections). Each strain of Hantavirus is uniquely adapted to its respective subclinically infected rodent reservoir. This evolutionary relationship is a product of millions of years of coadaptation. The genus Hantavirus comprises many strains that are pathogenic for humans. In the Old World, Hantaan, Seoul, Dobrava, and Puumala viruses are associated with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, whereas in the New World, Sin Nombre virus is the main virus involved in human cases of hantaviral pulmonary syndrome in North America. However, Monongahela, New York, Bayou, and Black Creek Canal viruses also cause hantaviral pulmonary syndrome and are found in eastern Canada and the eastern and southeastern regions of the United States. In South and Central America, several hantaviruses have been identified as causing hantaviral pulmonary syndrome, including Andes virus in Argentina and Chile; Andes-like viruses such as Oran, Lechiguanas, and Hu39694 in Argentina; Laguna Negra virus in Bolivia and Paraguay; Bermejo virus in Argentina; Juquitiba virus in Brazil; and Choclo virus in Panama (Table 19-1).101 TABLE 19-1 Comparison of Features of Some Zoonotic Hantavirus Infections HFRS, Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. aClosely related strains are New York, Peromyscus leucopus (white-footed mouse, eastern United States); Monongahela, Peromyscus maniculatus (deer mouse, eastern United States and Canada); Black Creek Canal, Sigmodon hispidus (cotton rat, Florida); Bayou, Oryzomys palustris (rice rat, southeastern United States). bClosely related strains are Oran, Oligoryzomys longicaudatus (Northwestern Argentina); Lechiguanas, O. flavescens (Central Argentina); HU39694, unknown reservoir (central Argentina). Although hantaviral infections in humans receive the most attention, the viruses have a wide potential host range among other mammals. Any role of the cat or dog in the transmission of hantaviruses from rodents to humans is quite unlikely, as indicated by a relatively low seropositive rate. The possibility of cats being at risk for hantaviral infection was initially raised by an epidemiologic study in China that indicated an increased risk factor of cat ownership for humans who developed hantaviral infection.110 Several studies conducted in Europe showed the presence of hantaviral antibodies in domestic cats. Five percent of outdoor cats in Austria were found to be seropositive, with higher titers against Puumala than the Hantaan strain.75 Similarly, serologic studies with cats in Great Britain showed an overall positive rate of 9.6%.6 The seropositive rate was much higher (23%) for cats with various chronic illnesses. Cats that are allowed to roam or hunt outdoors have the highest seroprevalence. Among 100 such cats, immunofluorescent detection of hantaviral antigen (using three different polyclonal anti-Puumala serum specimens) in lungs and kidneys showed the virus in specimens of lung from two cats.79 A serosurvey of rural cats and dogs from the southwestern Canadian prairie found a 2.9% seroprevalence rate for cats, whereas virus-specific antibodies were not found in dogs.56 In the United States, the Four Corners states (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah) have been the location of the majority of the human infections. In a serosurvey for hantaviral infection in Arizona, dogs and cats had a low prevalence (3.5% and 2.8%, respectively) of seroreactivity to nucleocapsid proteins of Sin Nombre virus.66 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of a few animals failed to amplify any hantaviral sequences. Neither coyotes nor dogs or cats appear to have a major role in the maintenance and transmission of Sin Nombre virus. Like humans, they likely acquire their infection from rodents and rodent excreta. No clinical signs have been attributed to hantaviral infection in cats. It is likely that their infection is asymptomatic because of the low carriage and quantities of virus.79 Clinical signs in humans vary according to the strain causing infection. Signs of Hantaan, Seoul, and Puumala infections are fever, headache, abdominal pain, renal dysfunction, and hemorrhagic diathesis. The hantaviral pulmonary syndrome of Sin Nombre virus begins with fever and flulike symptoms that progress to signs of pulmonary edema and shock. Radiographs reveal acute bilateral pulmonary interstitial infiltrates, which have been attributed to pulmonary vasculitis. Most deaths associated with hantaviral pulmonary syndrome are related to cardiac failure rather than pulmonary failure; therefore the term “hantaviral acute cardiopulmonary syndrome” is more appropriate than “hantaviral pulmonary syndrome.”101 Intravenous ribavirin, the RNA-inhibitory antiviral drug (see Chapter 2), has been effective in the treatment of human hantaviral infections when used early in the illness. Excessive fluid administration must be avoided because it may lead to severe edema and increase the severity of the pulmonary edema. Most humans become infected by the aerosol route when inhaling dust after disturbing rodent nests or closed spaces inhabited by infected mice. A few cases have been documented in which infection resulted from contact with urine-contaminated garbage and/or rodent bites. Avoiding contact with rodents and their excreta is the most effective way to reduce the prevalence of disease. Feral rodents should not be kept in captivity. Rodent-infested structures and soil contaminated with feces should be avoided because harmful aerosols can spread infection. Care should be taken when entering or cleaning closed buildings infested with rodents. Masks, and in some cases respirators, must always be worn by people cleaning rodent-infested areas. Areas to be cleaned should be thoroughly soaked with disinfectants such as dilute sodium hypochlorite before they are mopped. Vacuuming and sweeping should be avoided to minimize dust. Although cats have been found to be subclinically infected and test seropositive for exposure, it is unlikely that cat-to-cat or cat-to-human transmission occurs. An epidemiologic link between cat ownership and hantaviral disease has not been suspected in North America or Europe.79 Serologic studies in coyotes and domestic cats and dogs in the southwestern United States indicated seropositive rates of 0%, 2.8%, and 4.7%, respectively.66 The data suggest that these animals are not important in viral maintenance or in transmission of the infection to humans. Foot-and-mouth disease is a highly contagious illness of wild and domestic cloven-hoofed animals and is caused by strains of an Aphthovirus organism in the family Picornaviridae. It occurs worldwide; however, eradication has been variably successful in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, the British Isles, and North America. Carnivorous animals are relatively resistant to infection and do not play a major role in spreading or harboring the disease under conditions of natural exposure. The virus has been propagated in canine cell cultures.95 Dogs and cats can be experimentally infected36; however, no epizootics have been found among carnivores. These animals may become incidentally infected during outbreaks in herbivores by contacting these animals or their offal. Reports have been made of dogs that became infected by scavenging remains of dead animals.46,87 As a result of epizootics, guidelines have been established for dog owners in areas known to have infected animals.3 Dogs must be kept under control—on a leash or within an enclosure—at all times. Dogs should not be walked across farmland and should have minimal contact with livestock and wild animals. Certain sporting activities involving dogs should not be allowed in quarantined areas. Minimal restrictions have been placed on cats, although they should be kept indoors as much as possible. Disinfectants suitable for inactivating the virus are 4% sodium carbonate, 0.5% citric acid, 2% formalin, or 2% sodium hydroxide.84 Phenolic disinfectants, quaternary ammonium compounds, and biguanides are not effective. Halogens such as sodium hypochlorite or iodine are less effective because of inactivation by organic matter. A calicivirus that causes vesicular exanthema of swine produces lesions on the mouth, lips, snout, and feet and is often confused with foot-and-mouth disease. Dogs have developed clinical signs of illness characterized by vesicular eruptions when outbreaks of vesicular exanthema virus infection have occurred in swine.5 Virus was not definitely isolated in these cases. However, in other studies, experimentally infected dogs developed fever within 24 hours after inoculation and vesicular eruptions on their tongues and in their oral cavities.5 These lesions healed within a few days. Virus was isolated from the spleen of a dog that became febrile after inoculation. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an unclassified virus that causes an acute self-limiting hepatitis in people, pigs, and chickens in tropical and subtropical countries. Pigs may be important reservoirs for human infection.111 HEV infection is the most common form of acute hepatitis in human adults in regions of Asia. It has been reported in developing countries in southeast and central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. More sporadic outbreaks have occurred in Mexico and the United States and other countries in the Western Hemisphere. The virus is spherical and nonenveloped, ranging from 30 to 32 nm in diameter, with its nucleic acid in a single-stranded positive-sense RNA molecule. Although its structure resembles that of a calicivirus, its genome is closest to that of rubella virus, a member of the Togaviridae family. The strains found worldwide can be classified into three major genotypes. The virus is shed in feces with fecal–oral contact as the means of transmission. There has been concern, but no documented proof, that dogs and cats develop clinical illness from infection with HEV or transmit infection to people.4,55,103,109 Anti-HEV globulins have been detected in species of wild and domestic animals.97 Experimentally the virus has a broad host range. Chimpanzees, Old World and New World monkeys, pigs, rodents, and sheep have been experimentally infected. One swine isolate has been shown to have the broadest host range. Evidence of zoonotic transmission of infection occurred between a domestic pig and its owners.86 In one report, a person from Japan with hepatitis E who had not traveled was suspected to have become infected in the home environment.55 Fever, malaise, icterus, and brown-colored urine were observed in the family members. They were seronegative; however, the patient’s cat had a high HEV IgG titer. Although cats and dogs from Japan had antibodies to HEV in their sera, no virus could be detected by PCR of fecal specimens.68 A high percentage (33%) of pet cats in Japan were shown to have an increased serum antibody titer to HEV81; however, HEV DNA was not detected in the cats81 or in the livers of 98 dogs with a variety of forms of hepatitis.17 Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD) is an acute fatal disease of European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) caused by an RHD virus of the family Caliciviridae. The disease has been reported in Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Feral cats in New Zealand have antibodies to RHD virus, and nested reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR has identified virus in the liver of one seropositive cat.113 Cats fed rabbit livers infected with RHD virus developed serologic titers to the virus, and RHD viral RNA was detected in the tonsils, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, and liver. Even though large amounts of virus were found, clinical disease was not observed. Active replication of RHD virus was not demonstrated. As a group, the arenaviruses contain a number of geographically and genetically distinct members, some of which cause severe disease in people. Each arenavirus species is usually associated with a particular rodent reservoir host.47 Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is a ubiquitous zoonotic arenavirus of house mice (Mus musculus) that is transmitted in utero or at birth and persists for life in high concentrations in various tissues. Several outbreaks have been associated to pet hamsters, including accidental transmission of the infection in organ recipients.23 Outbreaks of rodent lymphocytic choriomeningitis infections have prompted concern that domestic dogs or cats might serve as reservoirs or vectors of the virus for human exposure. Puppies (8 to 12 weeks old) did not develop clinical illness after parenteral or cerebral inoculation.27 Challenged animals had increased neutralizing antibody titers to the virus, and infection was transmitted from infected to noninfected puppies. Except for intranuclear inclusions in the adrenal cortex, pathologic changes were not observed in the animals, indicating that the infection was subclinical. It is unlikely that dogs or cats become infected or spread the virus by natural exposure, because most human infections have resulted from direct contact with rodents. Immunocompromised people are most susceptible; postnatal infections cause acute aseptic meningoencephalitis, whereas congenital infections produce central nervous system (CNS) and ocular malformations.

Miscellaneous Viral Infections

Hantaviral Infection

Etiology

Disease

Viral Strain

Geographic Distribution

Reservoir Host

Usual Contact

Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS)

Hantaan

Korea, China, eastern Soviet Republics, Balkans

Apodemus agrarius (striped field mouse)

Agricultural activities

Nephropathia epidemica (milder HFRS)

Puumala

Scandinavia, western Soviet Republics, Europe,

Clethrionomys glariolus (bank vole)

Forests and agricultural hedgerows, rural and suburban gardens, high forest crop

Dobrava/Belgrade

Germany, Balkans, Russia, Estonia

Apodemus agrarius (striped field mouse) Apodemus flavicollis (yellow-necked field mouse)

Outdoor activities

Milder HFRS, chronic hypertensive renal failure

Seoul

Worldwide

Rattus norvegicus (Norway rat) and Rattus rattus (roof rat)

Farms and residential areas, laboratory rats outside U.S.

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

Sin Nombrea

Western and southwestern United States, Canada

Peromyscus maniculatus (deer mouse)

Human dwellings and outbuilding

Acute cardiopulmonary syndrome

Andesb

Argentina, Chile

Oligoryzomys longicaudatus (long-tailed pygmy rice rat)

Rodent contact, person-to-person

Laguna Negra

Paraguay, Bolivia

Calomys laucha (vesper mouse)

Rodent contact

Juquitiba

Brazil

Unknown

Unknown

Epidemiology

Clinical Findings

Therapy

Public Health Considerations

Foot-And-Mouth Disease

Vesicular Exanthema

Hepatitis E Virus Infection

Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree