Chapter 15 Miscellaneous unwelcome behaviors, their causes and resolution

Introduction

Physical causes of unwelcome behavioral responses should always be ruled out before any purely behavioral therapy is adopted. Painful lesions and other physical abnormalities should be eliminated because beyond their effects on horse welfare and development of annoying habits, they are likely to compromise athletic output (Fig. 15.1). For example, it has been proposed that undiagnosed pelvic or vertebral lesions could be important contributors to poor performance in horses.1 While occasional disorders such as ‘cold-back syndrome’ and the relationship between dental problems and behavior under-saddle have yet to be thoroughly explored, the treatment of most physical disorders that reduce performance is considered in detail in the veterinary literature.

Since most problem behaviors that emerge in stables or at pasture are considered elsewhere in this book, the current discussion will focus on handling problems and problems with the ridden horse. In combination with Chapters 1, 4 and 13, this chapter aims to help veterinarians and equine scientists in their creation, from first principles, of humane and effective therapies for unwelcome behaviors. The current chapter indicates the basic approaches to therapy that can be tailored for each affected horse, defines some of the more common problems and offers a framework for understanding the origins of these problems.

Unfortunately, as discussed in Chapter 13, there is a lack of scientific data in these realms. This may reflect the importance we place upon the performance of the horse under-saddle and the consequent development of riding instruction that tends to focus on outcomes rather than mechanisms. Since the ideals of equestrian technique combine art and science, students of equitation encounter measurable variables such as rhythm, tempo and outline alongside many more elusive qualities such as so-called submission.2,3 This mixture and the dearth of mechanistic substance frustrate attempts to express equestrian technique in empirical terms4 and account for some of the confusion and conflict that arises in many human–horse dyads. With time, the application of science to the plethora of undesirable behaviors that horses trial and learn to adopt will undoubtedly reduce the ill-considered demands for quick fixes and ultimately decrease the wastage in the industry. In terms of prevention, we will, in time, fully appreciate the importance of consistent, low-stress foundation training as the bedrock of any horse’s training and the best means of avoiding dangerous traits subsequently emerging.

Mechanical approaches

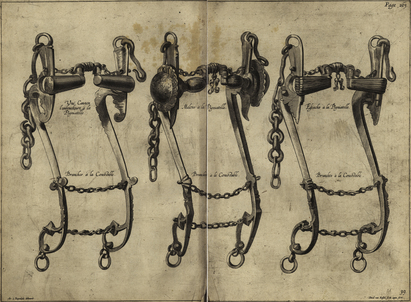

Frustrated trainers often try bits that apply pressure to different parts of the mouth or to the same area of the mouth but with greater severity (Fig. 15.2). Even though they can and sometimes do sever the tongue,5 saw-chain bits (so-called mule bits and correction bits) are readily available to riders who are having problems getting horses to respond to milder bits. If changing or increasing mouth pressure is unsuccessful, an alternative or additional means of making the horse adopt the desired shape is to apply pressure to other parts of the head, so training devices such as curb chains, gags, hackamores, bosals, draw reins, balancing reins and chambons may be employed. Unfortunately the tendency is to develop a reliance on these extra pulleys, rather than use them solely for retraining as the name might imply. Martingales and tie-downs are similar in that they apply pressure to prevent evasive raising of the head and are rarely dispensed with.

If the horse fails to show sufficient forward movement or impulsion, trainers direct their attention to the flanks where they can increase the pressure and more effectively drive the horse forward or simply away from the rider’s leg using whips and spurs. Although, for some, these stimulants are distasteful, they are not necessarily contraindicated since they can be used with subtlety and employed transiently to empower the rider’s leg signals. In contrast, tying horses’ heads down (with side reins and draw reins) and clamping their jaws shut with nosebands6 are counter-productive in the long term. Indeed there is growing concern that these approaches can automatically compromise welfare by virtue of their inflexibility and inherent absence of pressure-release.7

Behavior modification

Behavior therapy can help overcome undesirable equine responses that may have an innate component but are largely learned. The temptation may be to treat such traits in isolation. However, a holistic approach has tremendous merit since better results tend to occur if the human–horse relationship is nurtured when the rider is both on the ground and in the saddle. Time spent training horses in-hand seems to pay dividends even in the ridden horse,8 presumably through a process of generalization. Achieving stimulus control in-hand seems to facilitate stimulus control under-saddle.9 Inter-specific communication may help horses overcome fear and therefore reduce their tendency to use counter-predator responses. It is important that the translation of trained responses from cues in-hand to cues under-saddle is better understood by practitioners. It may simply be that an unconfused horse in-hand is a better prospect for training than a confused one. In any case, correctly identifying the effects of reduced confusion and fear and distinguishing stimulus control from mere compliance may allow us to describe and even measure the bonds that form between horses and their trainers.

By the same token, punishment is regarded by many owners as unenlightened, since it presupposes that horses know the difference between good and bad behavior. So, it is increasingly inappropriate for veterinarians to advocate punishment as a response to undesirable behavior in the horse. It undermines the human–horse bond and carries the risk of injury, which may place any practitioner who advises it in a legally liable position. Examples of acceptable techniques used for behavior modification include habituation and counter-conditioning (see Chs 4 and 13). Habituation is the key to overcoming fear-related responses such as traffic shyness but it can be expedited with counter-conditioning, an approach that relies heavily on the shaping of alternative responses through operant conditioning (see also Fig. 15.3). At its most elegant, equine operant conditioning takes the form of positive reinforcement and subtle negative reinforcement. Consistent use of negative reinforcement is the key to retraining the basics, but is notably more likely to work in horses that have not habituated to pressure. Techniques for restoring sensitivity to pressure cues demand exquisite timing of pressure-release. Meanwhile, clicker training employs positive secondary reinforcement that is particularly useful for refinement of responses, once negative reinforcement has established the basics.

Figure 15.3 Horse being clipped in the presence of food – an example of counter-conditioning.

(Reproduced with permission of Australian Equine Behaviour Centre.)

Horses with innate or learned evasion responses may have the rewarding outcomes of these responses removed by a process of extinction. Furthermore they can be trained to associate the fear-eliciting stimuli with positive outcomes in the same way that laboratory primates can be trained to voluntarily present their forelimbs for intravenous injections. (A case study that required a pony to learn to cope with hypodermic injections appears at the end of this chapter. It followed the injection desensitization training technique developed by ethologists at Pennsylvania State University.10) A far less humane approach to fearful horses is to flood them by exposing them to an overwhelming amount of the fear-eliciting stimulus in the hope that their responses are exhausted. For example, so-called ‘tarping’, a method of breaking by flooding, involves evoking learned helplessness by casting the horse, covering it with a tarpaulin and beating it until it no longer resists.

Practitioners are strongly encouraged to become extremely conversant with learning theory (see Ch. 4) before counseling owners on the application of these techniques. All of the undesirable responses in the current chapter can be remedied by behavior modification. But a prerequisite is to correctly identify the motivation for a given response. Readers are urged to consider the ethological content of this entire volume when determining causal factors. Beyond that the success of behavioral therapy depends on the consistency of administration and compliance of owners, who must be counseled that the latency for desirable outcomes depends largely on the number of times the horse has trialed and learned from the unwelcome response. With a thorough knowledge of learning theory, practitioners can customize behavior modification programs, modify advice in the light of initial responses and counsel owners when proximate results surprise the uninitiated. So, for example, when as a result of an extinction protocol, undesirable responses become more frequent, the accomplished student of learning theory can explain that this is a manifestation of the frustration effect (see p. 103 in Ch. 4) and that it is transient.

Handling problems

Horses fearful of clippers may have had a cutting injury or heat damage during clipping. Head shyness can be the manifestation of partial blindness, dental anomalies and, occasionally, spinose ear ticks.11 Girthing and saddling problems may be related to thoracic and spinal lesions. Horses that are eager to rub their heads against handlers may have lice or, very occasionally, flying insects or spinose ear ticks that make them generally itchy and sometimes irritable. In a similar vein, when acute in onset, hypersensitivity to being touched may be attributed to strychnine poisoning and even lightning strike.11

Assuming that painful pathologies have been ruled out, the role of learning is of tremendous significance in emergent handling problems. Horses showing fear of veterinarians may simply remember them as the immediate precursors of pain or of unpleasant physical restraint prior to painful interventions. Similarly, those showing fear of farriers (Fig. 15.4) may have received a nailing injury in the past. The horse’s ability to form general relationships between certain activities and pain should not be overlooked. For example, painful lesions (e.g. subclinical orthopedic disorders that are exacerbated by riding) may make a horse generally reluctant to work and, by a process of backward chaining (see Ch. 4), difficult to catch.

As with all behavior problems, it is the responsibility of handlers and therapists alike to establish that the horse is not only capable of an appropriate response but that it is also free from pain. Furthermore, the horse must know what is being asked of it, i.e. it must have learned the cue. Only when these prerequisites are in place can the horse be helped to unlearn the inappropriate associations (Table 15.1). Techniques in behavioral therapy can be used in combination so the suggestions that appear in Table 15.1 should not be considered the complete or sole approach. Attention to the horse’s dietary, social and environmental needs helps to advance the effects of appropriate behavior modification.

Table 15.1 Common handling problems, their interpretation and suggested approaches to therapy that can be employed after any primary physical causes have been removed

| Problem | Interpretation | Approaches to therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Barging (trampling) | ||

| Biting and bite threats | • Total refurbishment of the human–horse bond,a e.g. experienced personnel may make great strides with such horses in a roundpen | |

| Claustrophobia | ||

| Difficult to bridle | ||

| Difficult to saddle-up | ||

| Difficult to shoe | ||

| Dislike of grooming | ||

| Fear of being clipped | • Counter-conditioning.b Clicker training to approach and stand beside clippersc | |

| Fear of veterinarians | • Extinction of fear responses by habituation and counter-conditioning.b This should involve the owner in the first instance and then the practitioner • Clicker training of appropriate responses, such as approaching veterinarians and their equipmentc | |

| Hard to catch | ||

| Head rubbing | • Innate response to irritants Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|