Chapter 16 Miscellaneous Syndromes

Benign Essential (Idiopathic Renal) Hematuria In Dogs

Introduction and Pathophysiology

B. The renal hemorrhage usually is unilateral, but occasionally it may be bilateral. Either kidney may be affected but some reports suggest the left side is affected more frequently. At initial presentation, hemorrhage typically originates from one kidney. Nephrectomy resolves the clinical signs, but hemorrhage can develop in the remaining kidney at a later time.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Findings

A. Complete blood count (CBC) may show moderate to severe regenerative anemia. The anemia may be acute (i.e., macrocytosis, polychromasia, reticulocytosis) or chronic with evidence of iron deficiency (i.e., microcytosis, hypochromasia). Mild to moderate leukocytosis may be present.

B. Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentrations are normal and urine specific gravity shows moderately concentrated urine (i.e., renal function is normal).

Imaging Findings

Cystoscopy

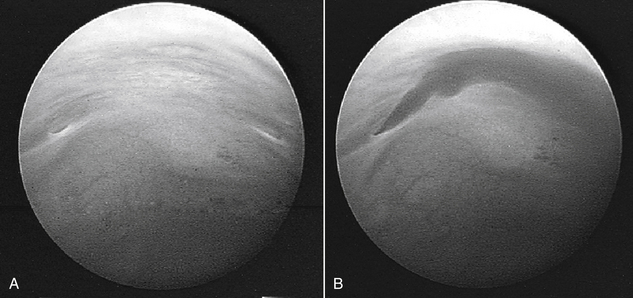

A. In female dogs, cystoscopy allows identification of the affected side by observation of normal urine flowing from one ureteral opening as compared with blood coming from the contralateral ureteral opening (Figure 16-1). If cystoscopy is not available, the affected side can be identified at surgery by passing catheters into each of the ureteral openings in the trigone region and determining from which side the hemorrhage arises.

Gross and Microscopic Pathology

A. Examination of removed kidneys shows blood clots in renal pelvis, ureter, or both. No other gross or histologic abnormalities typically are observed.

B. One affected dog was reported to have histologic evidence of chronic pyelitis, but urine culture was negative.

C. Abnormal small blood vessels below the urothelial surface of the renal pelvis were observed histologically in two affected dogs. These lesions resembled hemangiomas.

D. In one study, occasional small electron dense deposits were identified by electron microscopy in the glomerular mesangium in 5 of 9 affected dogs. The clinical relevance of these deposits is unknown.

Treatment

A. Nephrectomy should be considered if bleeding is documented to be unilateral and has been intractable and severe with development of severe anemia.

B. Nephrectomy resolves hematuria in dogs with unilateral renal hemorrhage, but some dogs have been reported to develop hemorrhage from the contralateral kidney some time after nephrectomy. Thus, the decision to perform nephrectomy should be weighed carefully.

C. Some affected dogs have intermittent periods of hemorrhage that are interspersed with long asymptomatic time periods. Thus, if there is no anemia or if anemia is mild, observation of the patient over time with monitoring of hematocrit may be preferable to nephrectomy.

D. In dogs with unilateral hemorrhage and severe anemia and in those with severe bilateral renal hemorrhage, symptomatic treatment with transfusions may be necessary.

E. Hydronephrosis or hydroureter due to obstruction of the distal ureter by a blood clot is another indication for surgery. In dogs with unilateral disease that have severe anemia and ureteral obstruction by blood clots, nephrectomy may be warranted.

F. Renal function typically does not deteriorate in affected dogs and consequently ureteral obstruction and severe anemia are the primary indications for nephrectomy in dogs with unilateral disease.

Prognosis

A. Good in dogs with severe bleeding due to unilateral disease that have undergone nephrectomy. The owner should be advised before surgery that hemorrhage from the contralateral kidney may occur in the future.

B. Fair to good in dogs with mild intermittent hematuria due to unilateral or bilateral disease with clinical monitoring. Long periods of remission may occur between episodes of hematuria.

Perinephric Pseudocysts (Pnp)

Introduction and Pathophysiology

A. Perinephric diseases are uncommon and consist of perinephric abscesses, hematomas, and pseudocysts.

B. A PNP is a fluid-filled fibrous sac surrounding the kidney. A transudative fluid accumulates between the renal capsule and the renal parenchyma. The term pseudocyst is used because the structure does not have the epithelial lining typical of a true cyst. The cyst is attached at the renal hilus (most commonly) or poles (less commonly) of the kidney.

D. The pseudocysts may be unilateral (approximately 60%) or bilateral (approximately 40%). Either kidney may be affected. Cats with unilateral pseudocysts may later develop a pseudocyst in the contralateral kidney.

F. Pseudocysts can be identified first with CRF occurring months to years later or cats can be diagnosed with CRF and develop pseudocysts 1 to 3 years later. Approximately 80% to 90% of cats with pseudocysts have at least mild CRF at the time of diagnosis. The relationship between PNP and CRF is unclear and may be incidental, as both are diseases of geriatric cats. Up to 25% to 30% of cats that live beyond 10 years of age are thought to develop CRF, and PNP are a rare complication even in this population of geriatric cats with CRF.

Diagnosis

Signalment

1. Typically, very old (geriatric) cats are affected (mean age 9 years). Approximately 80% are older than 8 years of age at presentation.

2. Early reports suggested male cats (80%) were more commonly affected than females (20%), but later studies indicated that both males (60%) and females (40%) may be affected.

History

2. Often affected cats have minimal clinical signs and the first abnormality detected by the owner is the abdominal distension.

3. Systemic signs of illness if present often are related to the presence and severity of accompanying CRF.

4. Occasionally, vomiting has been reported in cats with PNP without evidence of CRF, and it is speculated that pressure on or displacement of abdominal organs by the pseudocyst may lead to vomiting.

Physical Findings

B. A large mass or masses can be detected on abdominal palpation. It typically seems that one or both kidneys are extremely enlarged (i.e., 8 to 12 cm). It is impossible to differentiate a pseudocyst from renomegaly on the basis of palpation alone.

C. In cats with unilateral pseudocysts, the contralateral kidney may be small and irregular suggesting the presence of chronic renal disease.

D. Other physical findings (e.g., emaciation, dehydration, poor hair coat) are attributable to the presence of CRF.

F. Presence of a thyroid nodule should prompt evaluation for hyperthyroidism but CRF and PNP are systemic nonthyroidal illnesses that can cause serum thyroxine concentrations to be only mildly increased or within the normal reference range. Pertechnetate scanning may be indicated to definitively diagnose hyperthyroidism.

Laboratory Findings

A. The hemogram usually is normal. Nonregenerative anemia may be present if advanced CRF is present.

B. Serum biochemistry often shows evidence of mild to moderate CRF (i.e., mild to moderate increases in BUN and serum creatinine concentrations). Occasionally CRF may be severe.

D. Results of cytological analysis of fluid from the cysts almost always are typical of a transudate or, rarely, of a modified transudate.

E. Urinary tract infection (UTI) may be present in 40% or more of cats with PNP, and urine culture should be performed routinely as lower urinary tract signs typically are not present.

Imaging Findings

A. Plain abdominal radiographs demonstrate what appears to be a severely enlarged kidney or kidneys.

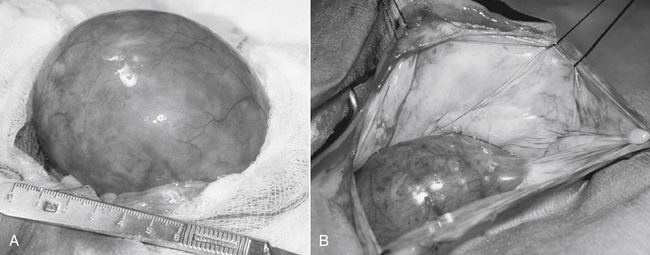

C. Abdominal ultrasonography is the diagnostic imaging procedure of choice and allows rapid diagnosis of PNP (i.e., the kidney is seen to be separated from the renal capsule and surrounded by anechoic fluid; the cyst typically occupies an area twice the size of the kidney; Figure 16-2). The presence of perinephric fluid of mixed echogenicity should prompt concern about the possibility of a perinephric abscess, perinephric hematoma, or neoplasia. Occasionally, cats with renal lymphoma will have small accumulations of perinephric fluid, as well as hypoechoic nodules in the renal parenchyma.

Treatment

A. Resection of the cyst wall is the most definitive treatment and allows any additional fluid accumulation into the peritoneum to be reabsorbed into the general circulation (Figure 16-3). In some cases, fluid accumulation may be mild to moderate and nonprogressive with minimal or no apparent discomfort to the cat. In such situations, medical surveillance and periodic ultrasound-guided drainage of the cyst as necessary may be a reasonable approach to management. In extremely rare instances, fluid accumulation may be so severe that detectable ascites may occur after cyst wall resection.

B. Do not remove the kidney on the affected side. Most of these cats have mild to moderate CRF with interstitial fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis. Removal of one kidney predisposes to rapid progression of renal disease in the contralateral kidney.

C. The pseudocysts may be drained under ultrasound guidance but fluid re-accumulates over the course of weeks to months. Drainage of the perinephric cyst has not been shown to improve glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in the affected kidney. Rarely, repeated ultrasound-guided drainage of a PNP will be associated with resolution of the cyst.

Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA)

Distal (Type I) Renal Tubular Acidosis

Diagnosis

A. UTI by a urease positive organism (e.g., Proteus sp, Staphylococcus aureus) must be ruled out before considering distal RTA.

B. Urinary net acid excretion is decreased, but bicarbonaturia usually is mild because urinary bicarbonate concentration is only 1 to 3 mEq/L in the pH range of 6.0 to 6.5.

C. Urinary fractional excretion of HCO3− is normal (<5%) in distal RTA when plasma HCO3− concentration is increased to normal by alkali administration.

D. A diagnosis of distal RTA can be confirmed by an ammonium chloride tolerance test during which urine pH is monitored (using a pH meter) before and at hourly intervals for 5 hours after oral administration of 0.2 g/kg NH4Cl. Under such conditions, the urine pH of normal dogs decreased to a minimum value of 5.16 at 4 hours after administration of ammonium chloride.

E. Nephrolithiasis (usually calcium phosphate stones), nephrocalcinosis (resulting from alkaline urine pH and decreased urinary citrate concentration), bone demineralization (resulting from loss of bone buffer stores during chronic acidosis), and urinary potassium wasting with hypokalemia are features of distal RTA in human patients.

F. Distal RTA has been reported in two cats with pyelonephritis caused by Escherichia coli. Clinical signs included PU, PD, anorexia, lethargy, enlarged kidneys, and isosthenuria. In one cat, urine pH was 5.0 at the time pyelonephritis was first diagnosed, but distal RTA was documented at a later time by the presence of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, alkaline urine pH, and failure to lower urine pH after oral administration of NH4Cl. Findings were similar for the other cat, but hyperphosphaturia and persistent hypokalemia also were detected.

Treatment

A. The amount of alkali required to correct the acidosis in human patients with distal RTA is variable but typically less than that required in proximal RTA. The required dosage of alkali in distal RTA may be as little as 1 mEq/kg/day (i.e., that required to offset daily endogenous acid production) or more than 2 to 4 mEq/kg/day.

B. A combination of potassium and sodium citrate (depending on potassium balance) may be the preferred source of alkali.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree