CHAPTER 15 Miscellaneous Skin Diseases

Eosinophilic granuloma

The eosinophilic granuloma is a common equine dermatosis and the most common inflammatory nodular skin disease of the horse.* It accounted for 3.9% of the equine skin disorders seen at the CUHA.

Cause and Pathogenesis

The cause and pathogenesis are often unknown and probably multifactorial. Because the lesions most commonly begin in spring and summer, insect-bite hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis have been suspected. However, in the northeast and Pacific northwest United States, many cases appear to begin in winter. Such cases would not be due to insect-bite hypersensitivity, but could still be due to winter time atopic dermatitis. Anecdotal reports indicate that horses with eosinophilic granuloma in association with atopic dermatitis have been controlled with allergen-specific immunotherapy (see Chapter 8).4,10 Anecdotal reports also suggest that food allergy may be a cause of eosinophilic granuloma.10

Because lesions commonly occur in the saddle region, some authors have suggested that trauma may be an inciting cause.4,6 Some horses develop eosinophilic granulomas at injection sites when standard silicone-coated needles are used.10,11,14 This may represent a hypersensitivity reaction to silicone, because the same horses do not develop reactions when noncoated stainless steel needles are used. In some biopsy specimens, free hair shafts may be seen.9 In these cases, there is often a history of body clipping prior to the onset of lesions, thus suggesting a causal relationship.

Classically, a characteristic histopathologic feature of the equine eosinophilic granuloma has been called “collagen degeneration,” “collagenolysis,” or “necrobiotic collagen” by various authors.6 However, there is no collagen degeneration in these lesions, and these characteristic histopathologic lesions are more appropriately called collagen flame figures.13

Clinical Features

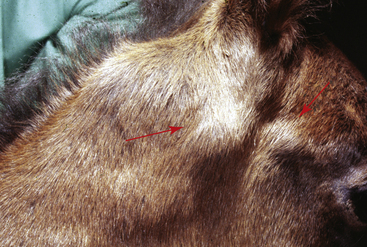

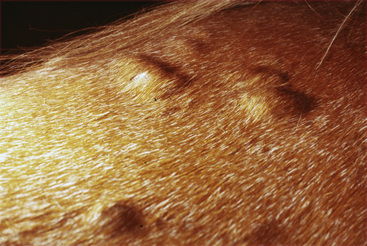

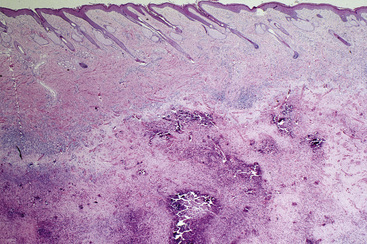

Eosinophilic granuloma (eosinophilic granuloma with collagen degeneration, nodular collagenolytic granuloma, acute collagen necrosis, nodular necrobiosis) is seen most commonly in spring and summer and has no apparent age, breed, or sex predilections.6 Single or multiple lesions most commonly occur on the back, withers, and neck (Figs. 15-1–15-6). They are round, elevated, firm, well-circumscribed, 0.5-10 cm in diameter, and the overlying skin and hair coat are typically normal. The lesions are neither painful nor pruritic. Cystic or plaquelike lesions are occasionally seen and may discharge a central, grayish-white caseous core (“necrotic plug”). Lesions can occur anywhere on the body, and an occasional horse can have hundreds of widely disseminated papular lesions (3-5 mm in diameter) (Fig. 15-7). Horses who have concurrent insect-bite hypersensitivity, atopic dermatitis, or food allergy will usually have clinical signs of those entities, as well (see Chapter 8).

Figure 15-1 Eosinophilic granuloma. Multiple asymptomatic papules and nodules over withers.

(Courtesy A. Stannard.)

Figure 15-7 Eosinophilic granuloma. Widespread asymptomatic papules and nodules.

(Courtesy A. Stannard.)

Diagnosis

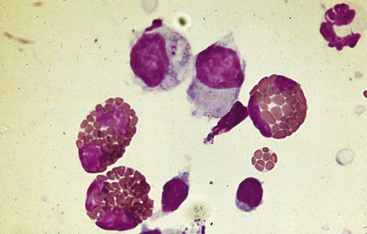

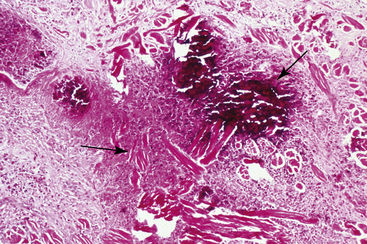

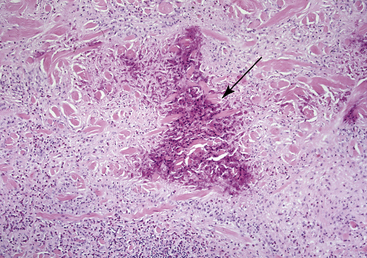

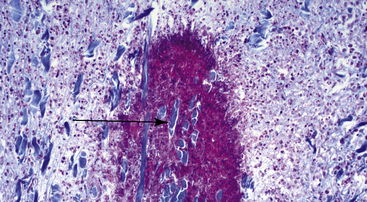

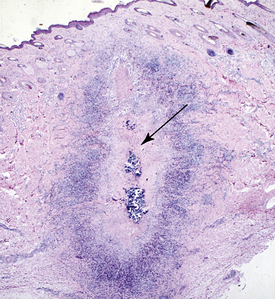

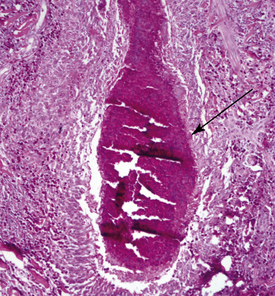

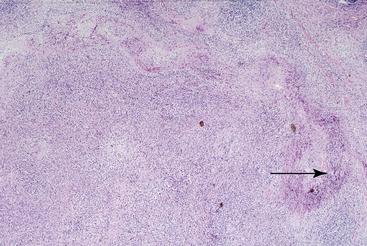

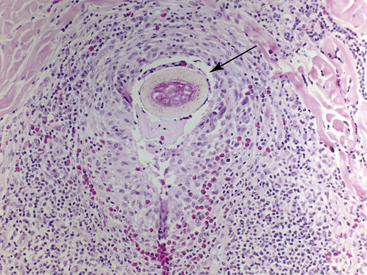

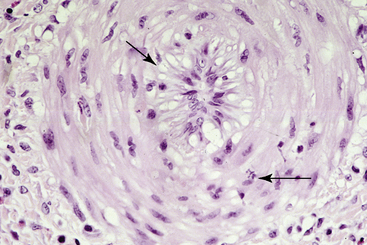

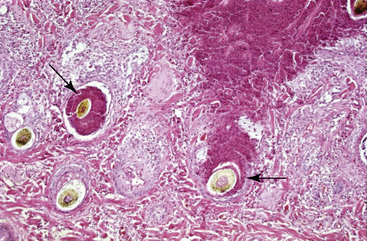

The differential diagnosis includes many of the nodular skin diseases in Table 15-1. Definitive diagnosis is based on history, physical examination, and skin biopsy. Cytologic examination reveals eosinophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes, and no microorganisms (Fig. 15-8). However, these lesions are often very firm and may not readily exfoliate. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is rare. Histopathologic findings include nodular-to-diffuse areas of eosinophilic, granulomatous inflammation of the dermis, and often the panniculus (Figs. 15-9 and 15-10). Multifocal areas of collagen flame figures are a characteristic finding (Figs. 15-10 and 15-11), and small foci of eosinophilic folliculitis or furunculosis may be seen (Fig. 15-12). Lymphoid nodules may be prominent. Older lesions exhibit marked dystrophic mineralization (Fig. 15-13) and may be misdiagnosed as calcinosis circumscripta or mast cell tumors. Special stains and cultures are negative. In silicone-coated needle injection reactions, the granulomatous process is often fairly linear in shape (Figs. 15-14 and 15-15), suggesting reaction along the needle tract. Hair shafts within a lesion suggest previous close-clipping (Fig. 15-16). Large areas of necrosis are not seen and, when present, suggest habronemiasis, pythiosis, zygomycosis, injection reactions, arthropod bite reactions, and mast cell tumors.

TABLE 15-1 Differential Diagnosis of Inflammatory Nodular Skin Disease6

| Disease | Common Site(s) |

|---|---|

| Bacterial | |

| Furunculosis (especially coagulase-positive staphylococci) | Saddle or tack areas |

| Ulcerative lymphangitis (especially Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis) | Legs |

| Actinomycosis | Mandible and maxilla |

| Nocardiosis | * |

| Abscess (especially C. pseudotuberculosis) | Chest and abdomen |

| Bacterial pseudomycetoma (especially coagulase-positive staphylococci) | Lips, legs and scrotum |

| Tuberculosis | Ventral thorax and abdomen; medial thighs, legs |

| Glanders | Medial hocks |

| Fungal | |

| Eumycotic mycetoma (especially Curvularia geniculata, black-grain; Pseudoallescheria boydii, white-grain) | Lips and legs |

| Phaeohyphomycosis (especially Bipolaris specifera) | * |

| Sporotrichosis | Legs |

| Zygomycosis | |

| Basidiobolus ranarum | Chest, trunk |

| Conidiobolus coronatus | Nostrils |

| Rhinosporidiosis | Nostrils |

| Alternariosis (Alternaria tenuis) | * |

| Blastomycosis | * |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Chest, shoulder |

| Cryptococcosis | * |

| Histoplasmosis farciminosi (Histoplasma farciminosum) | Face, neck, and legs |

| Pythiosis (Pythium insidiosum) | Legs, ventral chest, and abdomen |

| Parasitic | |

| Hypodermiasis (Hypoderma bovis, H. lineatum) | Withers |

| Habronemiasis (Habronema muscae, H. majus, Draschia megastoma) | Legs, ventrum, prepuce, and medial canthus |

| Parafilariasis (Parafilaria multipapillosa) | Neck, shoulders, and trunk |

| Halicephalobiasis | Prepuce, jaw |

| Tick bite granuloma | Face, neck, trunk, legs |

| Immunologic | |

| Urticaria | Neck, trunk, proximal legs |

| Erythema multiforme | Neck, dorsum |

| Amyloidosis | Head, neck, chest, and shoulders |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Eosinophilic granuloma | Neck, withers, and back |

| Axillary nodular necrosis | Near axilla and girth |

| Unilateral papular dermatosis | Trunk (one side!) |

| Exuberant granulation tissue | Legs |

| Panniculitis | Trunk, neck, proximal legs |

| Hematoma | Chest |

| Myospherulosis | * |

| Foreign body granuloma | Legs and ventrum |

| Calcinosis circumscripta | Lateral stifle |

| Nodular auricular chondropathy | Pinnae |

| Pseudolymphoma | Head and trunk |

* No apparent site(s) of predilection.

Figure 15-15 Same biopsy specimen as in Fig. 15-14. Central area of necrosis and dystrophic mineralization (arrow).

Figure 15-16 Eosinophilic granuloma following close-clipping. Skin biopsy reveals free hair shafts (arrow) within reaction.

Horses with other clinical features suggestive of insect-bite hypersensitivity, atopic dermatitis, or food allergy can be further delineated with insect avoidance, allergy testing, and novel diets and provocative exposure (see Chapter 8).

Clinical management

Horses with solitary lesions or a few lesions may be treated by surgical excision or sublesional injections of glucocorticoids (triamcinolone acetonide, 3-5 mg/lesion; methylprednisolone acetate, 5-10 mg/lesion).* Sublesional injections are typically repeated at 2-week intervals. Lesions still present after three injections will probably require surgical removal. Alternatively, as the lesions are usually asymptomatic, observation without treatment may be the preferred approach. Some lesions spontaneously regress. Horses with multiple lesions may be treated with systemic glucocorticoids (prednisolone or prednisone at 2 mg/kg orally (PO) every 24 h; dexamethasone 0.2 mg/kg PO every 24 h) given for 2-3 weeks. Some horses may suffer relapses, and retreatment is successful. Some lesions undergo spontaneous remission in 3-6 months. Older or larger lesions are often severely mineralized, do not respond to glucocorticoid therapy, and must be surgically excised.

Horses with eosinophilic granulomas in association with insect-bite hypersensitivity, atopic dermatitis, or food allergy will greatly benefit from therapy for these diseases (see Chapter 8).

Unilateral papular dermatosis

Unilateral papular dermatosis is a relatively rare equine dermatosis characterized by multiple asymptomatic papules on only one side of the body.1,4,6 It accounted for 1.2% of all the equine dermatoses seen at the CUHA.

Cause and Pathogenesis

The cause and pathogenesis of this disorder are unknown. Initial descriptions of the condition suggested that quarter horses had a genetic predilection. However, the disorder has been seen in several breeds of horses. Because many cases are seasonal (spring and summer), and the histopathologic findings of eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculosis are seen in many horses with various hypersensitivity disorders (insect-bite hypersensitivity, atopic dermatitis, food allergy, onchocerciasis), it has been hypothesized that unilateral papular dermatosis may represent an insect-bite hypersensitivity.6 The suspected hypersensitivity would occur on only one side of the body because of the insect’s preference to feed on the leeward side of the horse in windy conditions. If this were true, one wonders why the horse always stands in the same direction, and why most horses do not have repeated seasonal recurrences of the dermatosis. Perhaps the damage is caused by an ectoparasite inhabiting bedding and direct contact is involved.9

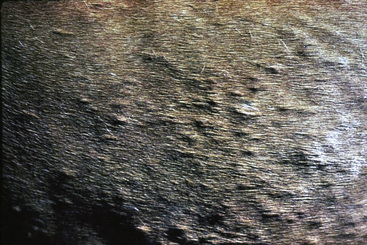

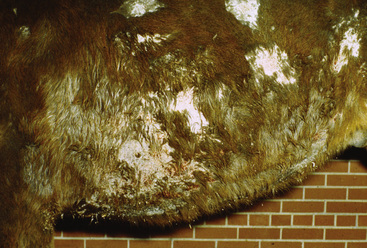

Clinical Features

There are no apparent age, breed, or sex predilections. Most horses develop lesions in spring and summer. The outstanding clinical feature of the condition is the occurrence of multiple (30-300) papules and occasionally nodules limited to one side of the body (Figs. 15-17–15-19). The lateral thorax is most commonly affected, but lesions may also be seen on the neck, shoulder, and abdomen. The early lesions are firm, rounded, elevated, well-circumscribed, tufted papules (Figs. 15-20 and 15-21). Pruritus and pain are absent. Some lesions become crusted and alopecic. Affected horses are otherwise healthy.

Figure 15-17 Unilateral papular dermatosis. Multiple papules on left side of trunk.

(Courtesy A. Stannard.)

Diagnosis

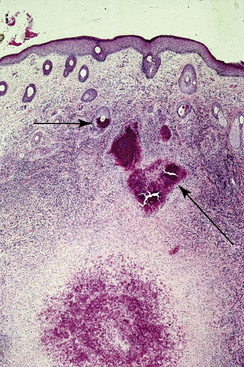

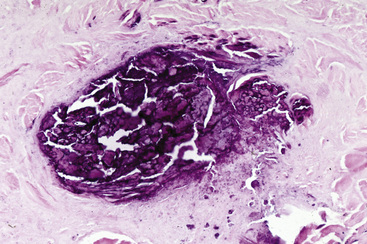

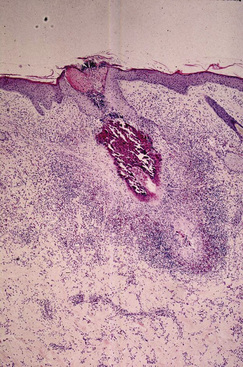

Unilateral papular dermatosis is visually distinctive. Cytologic examination reveals predominantly eosinophils and no microorganisms. Skin biopsy often reveals eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculosis (Figs. 15-22 and 15-23).6 Collagen flame figures may be seen in the surrounding dermis. In some cases, wedge-shaped areas of necrosis or superficial-to-mild dermal eosinophilic granulomas and necrosis, not clearly involving hair follicles, are found.9 Special stains and cultures are negative.

Clinical Management

Unilateral papular dermatosis typically undergoes spontaneous remission within several weeks to 6 months.6 Because of this and the asymptomatic nature of the disease, treatment is not usually attempted. Systemic glucocorticoids (2 mg/kg prednisolone or prednisone PO every 24 h; 0.2 mg/kg dexamethasone PO every 24 h) cause rapid resolution (2-3 weeks) of the dermatosis. Occasional horses suffer recurrences—on the same side or the opposite side of the body—in subsequent years.

Axillary nodular necrosis

Axillary nodular necrosis is a very rare dermatosis of the horse.1,4,6

Cause and Pathogenesis

The cause and pathogenesis are unknown. The disorder occurs at all times of the year. Vasculopathic changes have been described.6 It has been suggested that a more precise description for this dermatosis might be focal nodular eosinophilic granuloma and arteritis.

Owners often erroneously call the condition “girth galls” and attribute it to overworking or ill-fitting tack.9 However, the condition occurs in working and nonworking horses.

Clinical Features

There are no apparent age, breed, or sex predilections. Most horses have three or less (occasionally up to 10) nodules, 1-10 cm in diameter, typically present in the girth area behind the elbow (Figs. 15-24 and 15-25).6 However, lesions may be seen caudal to the shoulder and on the proximal, medial aspect of the forearm. The lesions are unilateral, rounded, well-circumscribed, and firm, and the overlying skin and hair coat appear normal. Some lesions may develop crateriform ulcers. They are neither pruritic nor painful. Multiple lesions may be arranged in chains and may be connected by a thin cord of palpable tissue (diseased artery?). Affected horses are otherwise normal.

Figure 15-24 Axillary nodular necrosis. Subcutaneous nodule in axillary region.

(Courtesy A. Stannard.)

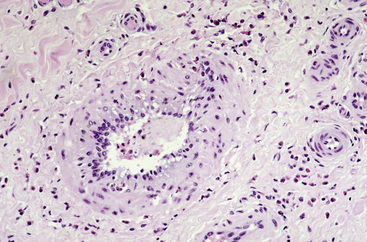

Diagnosis

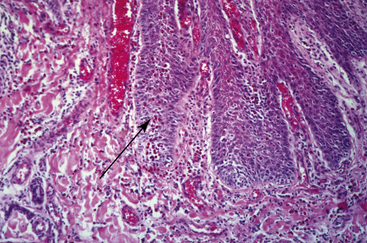

The differential diagnosis includes granulomatous disorders (infectious or sterile), neoplasia, or cyst. Definitive diagnosis is based on history, physical examination, and skin biopsy. Cytologic examination reveals eosinophilic to eosinophilic granulomatous inflammation, no microorganisms, and often numerous neutrophils. Histopathologic findings include interstitial-to-nodular-to-diffuse eosinophilic granulomatous dermatitis and panniculitis with focal necrosis (Fig. 15-26).6 Foci of collagen flame figures, dystrophic mineralization of collagen, palisaded granulomas, and lymphoid nodules are present. Vasculopathic changes include eosinophils associated with vacuolar changes in the tunica media and endothelium of deep dermal and subcutaneous arteries, small amounts of karyorrhectic nuclear material in the tunica media, endothelial cell hypertrophy and vessel occlusion, and intimal mucinosis (Figs. 15-27 and 15-28). Necrotizing arteritis is occasionally seen. Multiple specimens and multiple sections may be required to identify the vascular lesion.9 Special stains and cultures are negative.

Figure 15-27 Same biopsy specimen as Fig. 15-26. Note subendothelial mucinosis (left arrow) and occasional karyorrhectic leukocyte (right arrow) in vessel wall.

Sterile eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculosis

Sterile eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculitis is an uncommon cutaneous reaction pattern in the horse.6 It accounted for 0.6% of the equine dermatoses seen at the CUHA. Multiple lesions are present in a symmetric distribution and may be present anywhere on the body, although the neck, shoulder, brisket, and dorsolateral thorax are most commonly affected (Fig. 15-29). Tufted papules become crusted and alopecic. Pruritus is usually moderate to marked, but occasionally is mild. This cutaneous reaction pattern has been seen in horses with atopic dermatitis, insect-bite hypersensitivity, food allergy, and onchocerciasis.6 Other cases were idiopathic, but allergy testing was not done. Rarely, solitary areas of furunculosis are seen (Fig. 15-30). Solitary lesions may be reactions to focal insect or arachnid damage.

Figure 15-29 Sterile eosinophilic folliculitis in a horse with atopic dermatitis. Multiple tufted papules on brisket.

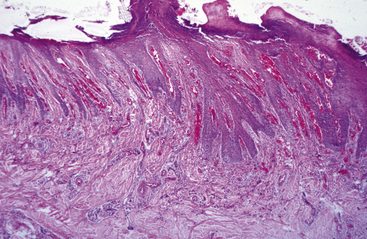

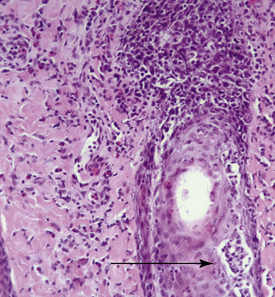

Cytologic examination reveals numerous eosinophils. Histopathologic findings include infiltrative-to-necrotizing eosinophilic mural folliculitis and furunculosis (Figs. 15-31 and 15-32) and, occasionally, focal collagen flame figures.6 Focal areas of eosinophilic mural folliculitis, luminal folliculitis, and furunculosis may be seen in biopsy specimens from horses with insect-bite hypersensitivity, atopic dermatitis, and food allergy in the corresponding clinical lesions (tufted papules). Special stains and cultures are negative. The diagnostic work-up could include drug withdrawal, ectoparasite control, novel protein diet, and intradermal testing to pursue underlying hypersensitivity disorders.

Figure 15-31 Skin biopsy specimen from horse in Fig. 15-29. Note necrotizing eosinophilic infiltrative folliculitis and furunculosis.

Figure 15-32 Skin biopsy specimen from horse in Fig. 15-30. Necrotizing eosinophilic infiltrative mural furunculosis (arrows).

Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease

This is a rare, sporadic disorder characterized by exfoliative dermatitis, ulcerative stomatitis, wasting, and infiltration of epithelial tissues by eosinophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages.3-6,16a It accounted for 0.2% of the equine dermatoses seen at the CUHA.

Cause and Pathogenesis

The cause and pathogenesis of this condition are unknown. Various authors have suggested hypersensitivity reactions to Strongylus equinus larvae, food allergens, or an epitheliotropic cell-associated virus.6 Swedish investigators have suggested a genetic basis for the syndrome in standardbreds.6 One horse had a concurrent intestinal lymphoma.17

Clinical Features

Although horses can be affected at any age, most are young (mean ages 3- to 4-years-old). Standardbreds and thoroughbreds account for about 70% and 20%, respectively, of all reported cases.6 There is no sex predilection.

The dermatitis usually begins insidiously with scaling, crusting, oozing, alopecia, and fissures on the coronets and/or the face (Figs. 15-33–15-35). Oral ulceration is often an early finding. Some horses initially develop well-demarcated ulcers on the coronary bands, muzzle, and mucocutaneous junctions. Rarely, vesicles and bullae are seen in these areas, or urticarial eruptions may be seen in the early phase of the disease. The dermatosis then develops into a generalized exfoliative dermatitis with scaling, crusting, easy epilation, alopecia, and focal areas of ulceration (Figs. 15-36–15-38). Pruritus is variable. Peripheral lymph nodes may be enlarged.

Figure 15-33 Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease. Alopecia, scaling, and ulceration on the face.

(Courtesy E. Guaguère.)

Figure 15-34 Same horse as in Fig. 15-33. Alopecia, scaling, and ulceration on the muzzle.

(Courtesy E. Guaguère.)

Figure 15-35 Same horse as in Figs. 15-33 and 15-34. Alopecia, ulceration, and oozing of distal legs and coronary bands.

(Courtesy E. Guaguère.)

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes pemphigus foliaceus, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, vasculitis, erythema multiforme, epitheliotropic lymphoma, cutaneous adverse drug reaction, and various toxicoses (vetch, stachybotryotoxicosis). The definitive diagnosis is based on history, physical examination, and biopsy results. The most common laboratory abnormalities are hypoalbuminemia (0.8-2.4 g/dL) in most horses, mild-to-moderate leukocytosis and neutrophilia (50% of the cases), and mild nonregenerative anemia (25%).6 Blood eosinophilia is rarely seen.6,16,18 Radiolabeled (51Cr) albumin studies reveal extensive gastrointestinal protein loss, and oral glucose tolerance tests demonstrated intestinal malabsorption.6 Attempts to isolate pathogenic microorganisms have not been successful.

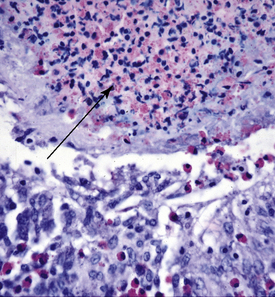

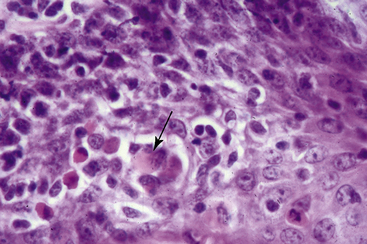

Dermatohistopathologic findings include an intermingling of inflammatory reaction patterns: superficial and deep perivascular, lichenoid interface, interstitial, diffuse, and granulomatous.6 Eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells are the dominant inflammatory cells. Epidermal hyperplasia is marked and irregular (Fig. 15-39). Hyperkeratosis is prominent and mixed (orthokeratotic and parakeratotic). An epitheliotropic infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes is typical, and apoptotic keratinocytes may be prominent (Figs. 15-40 through 15-42). Eosinophilic microabscesses and eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculosis may be seen. Foci of collagen flame figures or lymphoid nodule formation are occasionally seen. Neutrophilic microabscesses and suppurative folliculitis and furunculosis may be seen; these presumably reflect secondary bacterial infection. Direct immunofluorescence testing is negative.

Figure 15-40 Same biopsy specimen as in Fig. 15-39. Eosinophilic interstitial dermatitis and eosinophilic exocytosis (arrow) in hyperplastic epidermis.

Figure 15-41 Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease. Skin biopsy reveals pustular mural folliculitis (arrow).

Figure 15-42 Same biopsy specimen as in Fig. 15-41. Exocytosis of lymphocytes and eosinophils and apoptotic epidermal keratinocytes (arrow).

Rectal, liver, and lymph node biopsies are frequently performed to demonstrate the multisystemic nature of the disorder. Necropsy examination reveals involvement of multiple epithelial organs, especially pancreas, salivary glands, gastrointestinal tract, esophagus, liver, and bronchi. Lymph nodes, kidneys, spleen, and adrenal glands are also commonly affected. Nasal passages, larynx, and pharynx are rarely affected.16,18

Clinical Management

The prognosis varies with the chronicity and severity of the disease.3–6 Most horses suffer a progressive dermatitis and wasting over the course of several months (1-10) and are eventually euthanized or die. Large doses of glucocorticoids (2.2-4.4 mg/kg prednisolone or prednisone every 24 h, or 0.1-0.4 mg/kg dexamethasone every 24 h) may be effective if administered early in the course of the disease.6,16,18 Horses that do respond to glucocorticoids usually relapse when these drugs are discontinued. The combination of dexamethasone and hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg PO every 24 h) was ineffective in one horse.6 Horses with the wasting syndrome usually do not respond.

Because of the hypersensitivity-like inflammatory reaction that characterizes this disorder, the striking involvement of skin and gastrointestinal tract, and the poor response to glucocorticoids, food allergy is an attractive etiologic hypothesis. Novel protein diets should be evaluated in these horses (see Chapter 8).

Linear alopecia

Linear alopecia is a rare linear dermatosis of the horse.6,9,19

Cause and Pathogenesis

Because linear alopecia and linear keratosis (see Chapter 11) can coexist in some horses, it has been suggested that they are variations of the same abnormality.19 From a histopathological standpoint, this is hard to imagine.

Clinical Features

Circular areas of alopecia, usually in a linear vertically oriented configuration, are seen on the neck, shoulder, and/or lateral thorax areas (Fig. 15-43). One or more linear areas may be present. The lesions are usually 2-10 mm wide by a few centimeters to 1 m in length. Mild surface scale and/or crust may be present. The lesions are neither painful nor pruritic. Affected horses are otherwise healthy. In some cases, linear alopecia has coexisted with so-called “linear keratosis” (see Chapters 11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree