Chapter 48Mechanical and Neurological Lameness in the Forelimbs and Hindlimbs

Anatomical Considerations

A number of unique anatomical features in the equine hindlimb contribute to mechanical lameness. The configuration of the patellar ligaments in the stifle joint allows locking of the stifle into an extended position (see page 94). The stay apparatus minimizes the muscular effort required for a horse to stand for long periods. The reciprocal apparatus links the actions of the stifle and hock, primarily through the fibularis (peroneus) tertius and superficial digital flexor tendons, such that an abnormal action in either joint affects the action of both.

Upward Fixation of the Patella (Locking Stifle) and Delayed Release of the Patella

Clinical Characteristics

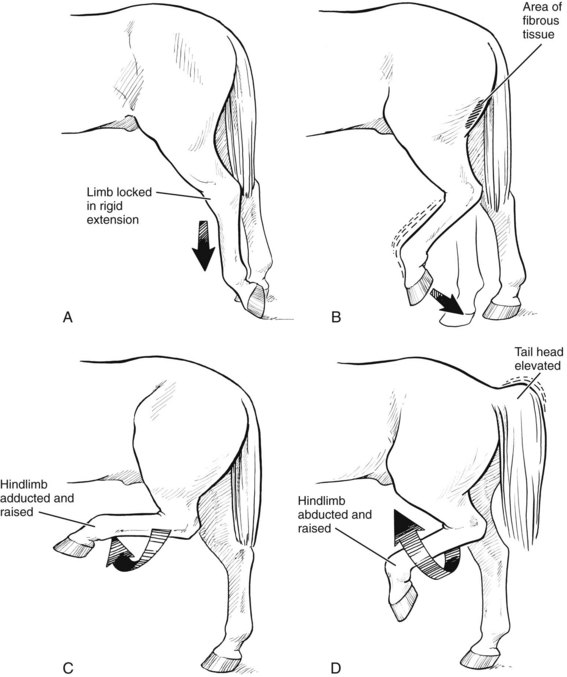

Horses and ponies with upward fixation of the patella are episodically unable to flex the stifle or the hock and drag the extended limb behind them on the toe (see Figures 5-18 and 48-1)![]() . The condition occurs most commonly after a period of standing still and tends to decrease with continued exercise. An intermittent form of patellar fixation, called delayed release of the patella, also occurs, in which the patella appears to catch briefly, sometimes followed by exaggerated flexion of the stifle and hock. Low-grade intermittent upward fixation or delayed release of the patella is relatively common, but it is often difficult to detect and is not necessarily observed daily. Affected horses have a slightly jerky movement of the patella that may be most apparent during deceleration from trot to walk and when the horse is working in deep footing, especially on turns. Affected horses may appear to be in some discomfort, may be resistant to work especially in deep footing, and can become irritable. Both upward fixation of the patella and delayed release may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Fifty-five of 78 horses (70.5%) with upward fixation of the patella were affected unilaterally and 23 (29.5%) bilaterally.6

. The condition occurs most commonly after a period of standing still and tends to decrease with continued exercise. An intermittent form of patellar fixation, called delayed release of the patella, also occurs, in which the patella appears to catch briefly, sometimes followed by exaggerated flexion of the stifle and hock. Low-grade intermittent upward fixation or delayed release of the patella is relatively common, but it is often difficult to detect and is not necessarily observed daily. Affected horses have a slightly jerky movement of the patella that may be most apparent during deceleration from trot to walk and when the horse is working in deep footing, especially on turns. Affected horses may appear to be in some discomfort, may be resistant to work especially in deep footing, and can become irritable. Both upward fixation of the patella and delayed release may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Fifty-five of 78 horses (70.5%) with upward fixation of the patella were affected unilaterally and 23 (29.5%) bilaterally.6

Cause

Upward fixation of the patella has been attributed to abnormal laxity and to increased tenseness of patellar ligaments. Decreased force of muscle contraction of the thigh muscles (quadriceps and biceps femoris) that move the patella out of the locked position may also cause upward fixation of the patella. This may be the explanation for upward fixation of the patella occurring in unfit horses, those in poor condition, or those with underlying myopathy, causing weak or stiff muscles. Horses and ponies with overly straight hindlimbs may be prone to upward fixation of the patella because such conformation can result in overextension of the stifle joint, leading to patellar locking.6,7 Sixteen of 78 horses (20.5%) with upward fixation of the patella had straight hindlimb conformation.6 Foot conformation may also play a role. Thirty-one of 78 horses (39.7%) had long toes and/or a higher inside wall of the hind foot of the affected limb(s).6 Permanent upward fixation of the patella occurs rarely secondary to luxation or subluxation of the ipsilateral coxofemoral joint (see Chapters 50 and 126).

Surgical Therapy

Medial patellar desmotomy may be necessary, although this should be considered only in horses with upward fixation of the patella that is unresponsive to conditioning exercise or medical therapy, or for horses that are persistently locked for several days. Because the transected ligament eventually heals with a fibrous union, the main benefit of surgery may be temporarily to alter the action of the stifle joint such that the horse is capable of conditioning exercise. Development of fragmentation of the apex of the patella (sometimes referred to as patellar chondromalacia) and associated lameness may occur after medial patellar desmotomy, although rest for 3 months postoperatively may reduce the risk (see Figure 46-4) (Figure 48-2).12 Treatment of fragmentation of the apex of the patella is by arthroscopic debridement (see Chapter 46). Middle patellar desmitis is also a potential untoward sequela.6,13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree