CHAPTER 61Mastitis

Mastitis is an inflammation of the mammary gland that occurs infrequently in the mare. The low incidence of mastitis in mares has been attributed to the small capacity and the protected location of the equine udder. Mastitis may affect mares of any age and reproductive state. Cases of mastitis have been reported in fillies as young as 1 day1 and mares as old as 24 years of age.2 The incidence of mastitis is similar in nonlactating and lactating mares. Mares are affected by four types of mastitis based on etiology: bacterial, mycotic, verminous, and avocado toxicity–associated mastitis.

MAMMARY GLAND ANATOMY

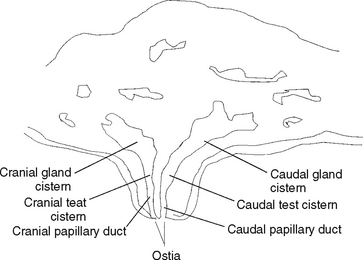

The two mammary glands of the mare are encased within the udder. The udder is located beneath the cranial portion of the pelvis and the caudal portion of the abdominal floor and is partially protected by the pelvic limbs. Covering the udder is a thin, sparsely haired, well-pigmented skin that is endowed with sweat and sebaceous glands.3 Grossly, the udder is divided into right and left halves by an external longitudinal intermammary groove,3 and at the base of each half is one laterally flattened teat. Each half of the udder contains one mamma. Each mamma is composed of lobes that are subdivided into lobules and secretory alveoli. Milk produced in the secretory alveoli passes into interlobular ducts4 that empty into lobar ducts and finally into a gland cistern. Each gland cistern drains a single mammary gland lobe. Milk passes from the gland cistern into the teat cistern and finally into the papillary duct (Figure 61-1). The papillary duct opens to the exterior via an ostium located in a depression at the apex of each teat. Two or three ostia are present in each teat, and each ostium represents the opening of a separate lactiferous duct system.3 The number and unique arrangement of teat ostia complicate treatment of mammary gland conditions.

Mammary development in the mare varies with reproductive status of the animal. The equine udder is smallest in the nulliparous mare and increases in size to a capacity of approximately 2 L5 in the lactating mare. Both the protected location and the small size of the udder minimize the incidence of mammary gland pathologic conditions in the mare.

BACTERIAL MASTITIS

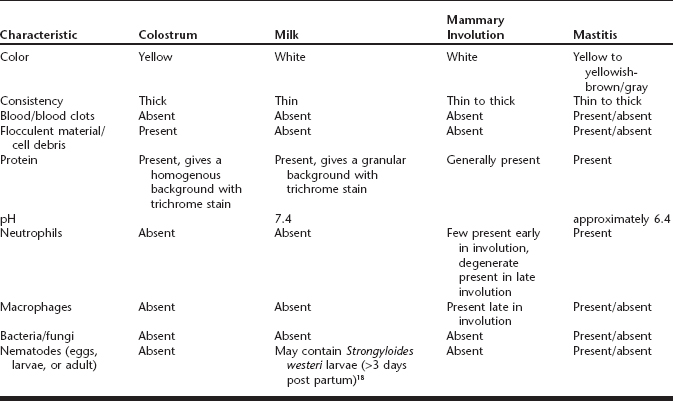

The most common type of mastitis affecting mares is bacterial. Mares with bacterial mastitis will often have an insect sting, injury, or laceration of the teat or udder on the affected side and will present with a swollen, firm udder that is warm and/or painful to palpation (Box 61-1).2 One or both mammae may be affected. Other signs may include ventral edema extending from the udder cranially and/or caudally and unilateral or bilateral hindlimb lameness ipsilateral to the affected mamma. Systemic signs may be present or absent and will vary between mares and causes. Common systemic signs include pyrexia, lethargy, and depression. Less commonly mares present with anorexia, sweating, elevated pulse and respiratory rates,6 neutrophilia, and/or hyperfibrinogenamia.2 The affected mammary gland will produce secretions that vary in consistency from milky to thick (Table 61-1). Mammary secretions from affected glands will vary in appearance (see Table 61-1) from a yellow to yellowish-brown or yellowish-gray in color6,7 and may contain blood and/or flocculent material.7,8 The mammary secretions should be evaluated to determine the type and severity of the mastitis.

Mammary secretions from a suspect mare should be collected for pathogen isolation and cytologic evaluation. Before sample collection, the teat should be cleaned with a dry gauze sponge and several streams of fluid should be stripped from the teat to reduce contaminants.9 A 2- to 3-ml sample is then collected into a sterile container for analysis. Both pathogen isolation from and cytologic evaluation of the mammary secretions may be used to confirm the diagnosis of mastitis.

Less common techniques used to confirm the presence of mastitis include the California Mastitis Test or ultrasonography of the udder.10 The California Mastitis Test is commonly used for dairy cattle but rarely used in horses. Ultrasonography of the udder allows one to distinguish between mastitis and other mammary gland lesions such as mammary gland abscesses and tumors (Box 61-2). Although both techniques can be useful, identification of the pathogen and cytologic evaluation of the mammary secretions are the preferred methods for diagnostic confirmation of mastitis.

Box 61-2 Differential Diagnoses for Equine Mastitis

Normal periparturient mammary development

Normal mammary gland involution

Several bacterial species have been isolated from mammary gland secretions of affected mares (Table 61-2). Of these organisms, Streptococcus sp. account for over half of the observed cases of equine mastitis, and the most common isolate is S. zooepidemicus. Other commonly isolated organisms are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp., Staphylococcus sp., and Corynebacterium sp. Several other bacterial species have been reported, but these are infrequently observed (see Table 61-2). Most cases of equine bacterial mastitis are caused by a single organism. However, multiple organisms are cultured in approximately 5% of the cases examined.

Table 61-2 Bacterial Isolates from Equine Mastitis

| Organisms | Percent of Isolates* | References |

| Actinobacillus sp. | 2.8 | McCue and Wilson,2 Carmalt et al19 |

| A. lignieresii | 0.9† | Carmalt et al19 |

| A. suis | 1.9‡ | McCue and Wilson2 |

| Actinomycetes sp | 0.9† | Delorme and Hamelin1 |

| Bacillus sp. | 0.9 | Albrecht and Samper20 |

| Corynebacterium sp. | 3.7 | Addo et al,7 Albrecht and Samper,20 Seahorn et al21 |

| C. ovis | 0.9 | Addo et al7 |

| C. | 0.9 |