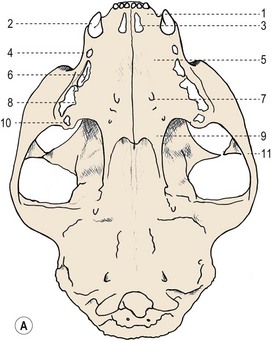

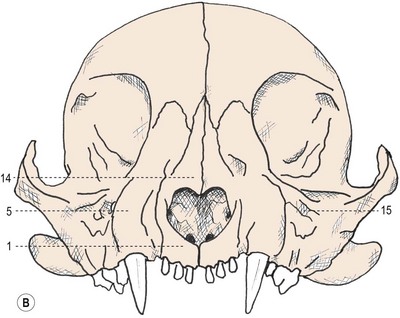

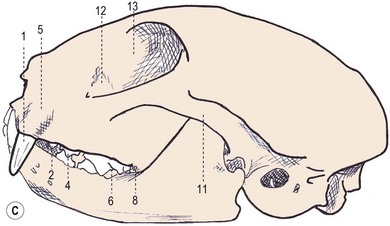

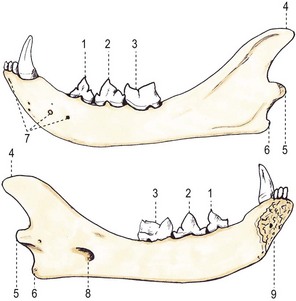

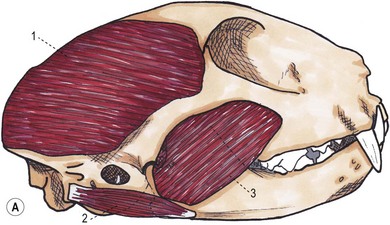

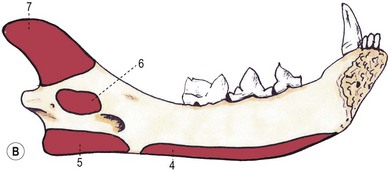

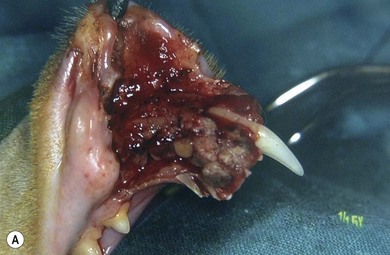

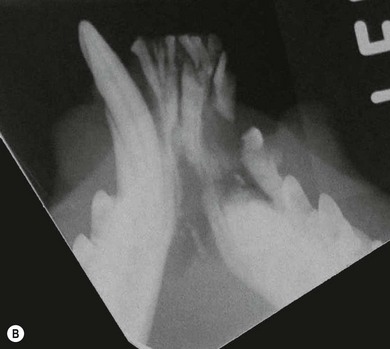

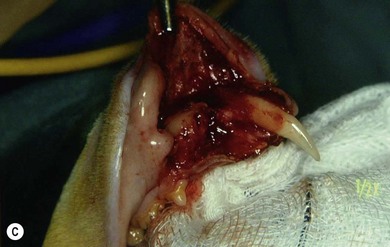

Chapter 55 There are several indications for surgery of the maxilla and mandible in feline patients; this chapter will describe the indications and techniques of mandibulectomy and maxillectomy. There has traditionally been an assumption that cats do not tolerate such procedures well although this assumption has largely been based on opinion and anecdote with only limited documented information available for review. Indications for these procedures include oral neoplasia, non-neoplastic oral lesions, intractable infection, and traumatic injuries. The most commonly encountered oral tumors are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and fibrosarcoma, both of which are locally invasive and frequently invade bone. Maxillectomy and mandibulectomy allow resection of these tumors with wide margins,1–4 and therefore provide potentially curative treatment. Traumatic injuries such as bite wounds, projectile injuries, and road traffic accidents may result in a degree of dysfunction that is not compatible with life, but which may be addressed via maxillectomy or mandibulectomy in a way that allows a good quality of life and normal or near normal function to be restored. Fractures of the mandible and disorders of the temporomandibular joint including ankylosis and locking-jaw syndrome are common in the cat and these are covered in Chapter 26 of Feline Orthopedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Disease.5 The skull is a rigid structure made up of many bones, which articulates with the mandible at the two temporomandibular joints (Fig. 55-1). Maxillectomy may require removal of part or all of the maxilla, incisive, palatine, frontal, vomer, zygomatic, and lacrimal bones, so a thorough knowledge of regional anatomy is essential. The mandible is comprised of two hemimandibles firmly united rostrally at the mandibular symphysis (Fig. 55-2). The horizontal part is termed the body and the vertical part the ramus. The permanent dentition of the cat is coded 2(I3/3–C1/1–P3/2–M1/1), although in the experience of the authors use of this terminology is not consistent amongst veterinary surgeons. The premolars are numbered 2–4 on the upper arcade and 3–4 on the lower arcade.6 Figure 55-1 Three views of the feline skull are provided in this figure, lateral, ventrodorsal, and rostral. 1, Incisive bone; 2, canine tooth; 3, palatine fissure; 4, upper premolar 2; 5, maxilla; 6, upper premolar 3; 7, palatine foramen; 8, upper premolar 4; 9, palatine bone; 10, upper molar 1; 11, zygomatic arch; 12, lacrimal bone; 13, frontal bone; 14, nasal bone; 15, infraorbital foramen. Figure 55-2 Two views of the feline mandible are provided in this figure, medial and lateral. 1, Premolar 3; 2, premolar 4; 3, molar 1; 4, coronoid process; 5, condylar process; 6, angular process; 7, mental foramina; 8, mandibular foramen; 9, mandibular symphysis. The muscles of mastication attach mainly to the ramus of the mandible (Fig. 55-3). The temporalis muscle attaches to the coronoid process and the pterygoid muscles attach medially and caudally, ventral to the temporalis attachment. The masseter arises from the zygomatic process and attaches to the ventrolateral surface at the masseteric fossa. The digastricus attaches to the mandibular body. Figure 55-3 This picture illustrates the muscles of mastication on the lateral skull and the insertions on the medial mandible. 1, Temporalis; 2, digastricus; 3, masseter; 4, attachment of mylohyoideus; 5, attachment of digastricus; 6, attachment of medial pterygoid; 7, attachment of temporalis A minimum database of hematology, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, and feline leukemia virus (FeLV)/feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) status should always be obtained prior to further diagnostic procedures, and a thorough examination of the oral cavity under general anesthesia is mandatory to fully assess the extent of disease. As the majority of feline oral masses are malignant, full staging is essential (see Chapter 14). Lymphatic spread is typically to the submandibular lymph nodes initially, then to the mediastinal and prescapular lymph nodes via the cervical chain.7 Distant metastatic disease may be to the lungs, or other organs depending on the primary tumor type. Diagnostic imaging is essential to assess the extent of the tumor and the invasion of local bone. Orthogonal radiographs of the skull as well as intraoral views may be used to assess invasion of bone via lysis or new bone production. However, radiographs may underestimate the extent of the tumor, as lysis is only evident once 40% of bone cortex has been destroyed.8 Computed tomography combining plain and contrast images is very useful to assess maxillary masses that extend into the nasal cavity, and caudal mandibular masses,9 and provides an enhanced level of detail over conventional radiography.10,11 In one study, just over half of cats and dogs with regional lymph node metastasis from oral tumors had submandibular lymph node enlargement,12 although the likelihood of local lymphatic disease varies with tumor type. However, palpation of local and regional lymph nodes is not a sensitive test for lymph node metastasis and, as a minimum, fine needle aspiration for cytology should be performed. There is an argument, however, for performing either incisional or excisional biopsy in preference to aspiration as this is a more accurate way of staging local disease.13,14 Tumor surface inflammation and necrosis mean that touch cytology preparations are often non-diagnostic or misleading and are therefore not recommended. Biopsy is essential in determining the nature of an oral tumor. The biopsy tract should form part of the tissue that will be excised and should avoid normal peripheral tissues to prevent contamination. In humans, incisional biopsy of oral SCC results in transient release of tumor cells into the blood but there is no supporting evidence for biopsy-induced metastasis in small animals and the overall prognosis remains unaffected provided the biopsy tract has been correctly placed.15 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oral neoplasm in cats, comprising approximately 61–80% of all oral tumors.16,17 Development of oral SCC has been linked with environmental factors such as the use of flea collars, diet, and passive smoking.18,19 Affected cats have a median age of 10–12 years and there is no sex predisposition. Grossly, the appearance is variable and may be proliferative or ulcerative, underlining the importance of biopsy for accurate diagnosis. Invasion of bone is common in feline oral SCC and is often aggressive with osteolysis, infection, and associated tooth loss.20 Regional lymph node metastasis occurs in less than 25% of cases and distant metastasis is rare.17 In the dog, the metastatic rate is site dependent, with rostral tumors having a lower metastatic potential than caudal or tonsilar SCCs.21 There is currently no evidence that this is the case in the cat. A syndrome of paraneoplastic hypercalcemia has been described in two cats with SCC.22 Oral fibrosarcoma is the second most common oral neoplasm of cats, comprising approximately 13–17% of all oral tumors.17 Affected cats have a median age of 10 years and there is no sex predisposition. Grossly, lesions characteristically appear firm and solid. These are locally aggressive tumors and bone involvement is common; however, the metastatic rate to regional and distant sites is low. In dogs the lungs are the most common site for metastasis,23 but it is not clear if this is the case in the cat.24 Malignant melanoma is rare in cats, accounting for only 0.8% of feline oral tumors in a ten-year survey carried out in 1989; unfortunately, more recent data is not available.16 Once again, it is locally aggressive although metastasis has not been reported in the cat. Osteosarcoma accounts for 2.4% of feline oral tumors and seems to be more commonly seen in the maxilla, although available numbers for analysis are low and the data is now quite old so its reliability is uncertain.16 Although one study suggested that mandibular osteosarcoma in cats is associated with a good two-year survival rate,24 two further studies concluded that axial osteosarcoma carried a poorer prognosis with shorter survival times when compared with feline appendicular osteosarcoma. Other tumor types reported include salivary gland adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, chondrosarcoma and osteoma, but these are more rare occurrences.16,25 Epulis is a clinical ‘umbrella’ term used to describe any one of a group of diseases characterized by grossly visible gingival proliferation; as such it does not constitute a histologic diagnosis.26 In cats, epulides have been classified into four types: fibromatous, ossifying, acanthomatous, and giant cell. Fibromatous epulis was described as the third most common oral tumor in cats in the 1989 survey, representing 7.8% of all feline oral tumors.16 However, a more recent study showed most fibromatous epulides also had acanthomatous and ossifying components so the true distribution is difficult to assess.26 Lesions may be solitary or multiple, with multiple tumors being relatively common in cats under three years old.26,27 Granulomas, which may be pyogenic or peripheral giant cell in nature, may resemble epulides grossly,16,28 but peripheral giant cell epulis has been documented to show aggressive behavior such as rapid growth, ulceration, and osteolysis, which is not typical for most epulides.26 Odontogenic tumors or ameloblastomas are tumors of the epithelial cells of the dental lamina, and may resemble epulides clinically and histologically.16 In dogs, fibromatous and ossifying epulides have been reclassified as peripheral odontogenic fibromas, but in cats it is still not clear whether they may be considered separate diseases.16 Feline inductive odontogenic tumors, also known less correctly as feline inductive fibroameloblastoma, are unique to cats29 and are most commonly seen in the rostral maxilla. They are described in young cats and may be locally invasive although metastasis has not been described. Amyloid-producing odontogenic tumors are rare in cats and may be locally invasive but do not seem to metastasize.30 Odontogenic cysts have been described in cats and may be maxillary or mandibular in nature.31 Fractures of the mandible and maxilla may not always be amenable to repair, depending on location and severity. In some patients teeth may be absent, bone quality poor, periodontal disease may be severe, osteomyelitis may be present, or the fracture line may pass through an alveolus. In such cases partial mandibulectomy or maxillectomy may offer a superior prognosis to primary fracture repair, with a better quality of life and function (Fig. 55-4). To date, however, this treatment concept is only poorly documented in the available literature, and has been described in only a small case series in the dog32 and not at all in cats. This means that unfortunately this aspect of orofacial surgery is currently based largely on individual experience and clinical anecdote rather than on widely available evidence. Partial maxillectomy has been reported in the management of oronasal fistula in the dog,33 but there are no similar reports in the cat. Figure 55-4 (A) Comminuted, open and contaminated rostral mandibular fracture in a three-year-old male neutered domestic long-haired cat that had been involved in a road traffic accident. (B) Intraoral radiograph shows comminution and loss of some of the incisors and rostral mandible. (C) The remaining rostral mandible and incisors were debrided. (D) Primary closure was possible. Tumors may be surrounded by a pseudocapsule (a mix of normal and neoplastic cells) and/or a reactive zone (mainly inflammatory cells),34 and these must be taken in to account with surgical planning and selection of appropriate margins. Removal of the tumor from within the pseudocapsule, an intracapsular resection, is rarely indicated but may be suitable when curetting a well-differentiated odontoma from the mandible. A marginal excision involves removal of the tumor by dissection in the reactive zone and is appropriate for some benign tumors but never for a malignant tumor.35 Where the tumor is malignant and local infiltration is expected, wide excision is indicated. A benchmark of 10 mm is often used in veterinary medicine, based on recommendations for resection of oral SCCs in humans.36,37 In reality, this margin has had little validation in veterinary medicine and may not be universally applicable, particularly for tumors that are considered less invasive or aggressive in nature.34 More locally invasive and infiltrative tumors such as fibrosarcomas or feline squamous cell carcinomas, on the other hand, may require margins greater than 10 mm, and many surgeons will take 1.5–2 cm margins for oral sarcomas. This margin, however, is to a large extent arbitrary in nature, and its use has not been validated for clinical cases. Wide resection is typically achieved through partial mandibulectomy or maxillectomy whereas radical excision requires total hemimandibulectomy or rostral maxillectomy.38 Tissues of the oral cavity will heal readily due to good blood supply; however, basic principles of good surgical technique remain important and atraumatic tissue handling is essential. As most osteotomies will be performed with powered equipment, there is a tendency for irrigation with sterile saline during use to prevent thermal damage, although this is once again an approach that has not been clinically validated and is based largely on opinion rather than evidence. Oral tumor resections are considered clean-contaminated surgeries. In humans, such surgeries are considered to warrant prophylactic intravenous antibiosis.39 Amoxicillin-clavulanate, some cephalosporins, and clindamycin have been suggested as the most appropriate for perioperative use in cats, based on the typical oral flora, but it should be borne in mind that this recommendation is now over 15 years old.40 Sensory nerve blocks of the infraorbital and inferior alveolar nerves41 provide excellent analgesia and can prevent central sensitization, therefore they form a very useful part of a multimodal analgesic protocol (see Chapter 2). Blocking the infraorbital nerve will desensitize the upper dental arcade, the soft and hard palates ipsilaterally, and the muzzle. Blocking the inferior alveolar nerve will desensitize the lower dental arcade and chin. The patient is placed in lateral recumbency for most unilateral maxillectomy and mandibulectomy surgeries although for bilateral procedures dorsal or sternal recumbency may be preferable. The oropharynx is packed and hair is clipped on the affected side. The extent of the clip is dictated by the planned procedure, so for a partial hemimandibulectomy it may be adequate to clip ventral to the eye, whereas a maxillectomy involving partial orbitectomy may require a considerably wider clip. The planned reconstruction will also dictate the clip; for example, if the use of an omocervical flap (see Chapter 19) is anticipated then the clip must extend down the neck for the appropriate distance. The planned placement of a feeding tube at the end of the procedure will also require additional preoperative clipping. The mouth and skin are prepared aseptically; in people, chlorhexidine is considered most suitable for oral preparation,42 but there are no similar studies in animals and povidone-iodine is commonly used for oral preparation. Following aseptic preparation and draping, the planned margins of the incision are outlined with a sterile skin marker. Maxillectomy is performed at varying levels based on the location and extent of tissue to be removed and may be rostral, central, caudal, unilateral, or bilateral in differing combinations (Boxes 55-1 and 55-2; Fig. 55-5A,B).

Mandibulectomy and maxillectomy

Surgical anatomy

General considerations

Diagnostic procedures

Surgical diseases

Neoplastic diseases

Epulides and odontogenic tumors

Other surgical conditions

General preoperative surgical considerations

Margins

Healing

Analgesia

Surgical techniques

Maxillectomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Mandibulectomy and maxillectomy