Rick W. Henninger

Managing an Outbreak of Infectious Disease

The threat of an infectious disease outbreak is ever present in all groups of horses, regardless of age, sex, breed, or use of horse. However, outbreaks are most often associated with situations in which horses from different locations congregate in large groups, such as at racetracks, horse shows, boarding or riding facilities, breeding farms, and equine hospitals. Horses in these situations are often subjected to travel as well as to changes in environment, management, social groups, and diet. Additionally, they are often housed in large facilities with shared airspace and close contact between horses. It is likely that the stress imposed on horses in these situations and the close contact between horses at such facilities play an important role in the development and dissemination of infectious disease. Stress potentially influences susceptibility to infection as well as contributes to reactivation of viral infections in latently infected horses and shedding of bacterial pathogens in carrier horses. Other facility-related factors that influence development of an outbreak include the number and ages of horses on the premises, layout and ventilation of the facility, and general sanitation and biosecurity practices.

Practically speaking, the above-mentioned variables that may contribute to the development of an outbreak are not amenable to change. Therefore the best defense against infectious disease outbreaks is to implement as comprehensive a biosecurity plan as is practical (see Chapter 30). Although disease control measures offer no guarantee against the development of an outbreak of infectious disease, they will certainly reduce the risk for introduction of infectious agents as well as serve to limit the spread of an infectious disease within a facility. Furthermore, the institution of daily infection prevention measures familiarizes personnel with the principles and practices used to manage an infectious disease outbreak. The management of an outbreak of infectious disease can be an extremely expensive and agonizing venture. By definition, an outbreak of infectious disease is associated with high rates of morbidity, which results in loss of performance time and suffering in affected horses. The costs associated with the management, diagnostic testing, treatment, and lost income are high. Outbreaks associated with high mortality rates carry the additional burden of extreme anguish among owners and personnel. The adverse public perception that often surrounds an outbreak of infectious disease lasts well beyond the end of the outbreak.

Managing an Outbreak

There is no universal plan that applies to the management of every infectious disease outbreak. The strategies must be tailored to each facility and are dictated by many variables. The disease involved, its mode of transmission, number of horses affected, and zoonotic potential of the disease are of primary concern at the onset of an outbreak. Many factors inherent to the facility itself have a direct influence on the management plan. The size of the facility, ventilation, type of floor and stall surfaces, availability of separate areas for isolation purposes, number of employees and their abilities, and economic constraints must all be taken into consideration. The general steps involved in the management of an outbreak are the following:

1. Identification and examination of initial sick horses

2. Pursuit of a specific diagnosis

3. Establishment of isolation areas and institution of specific isolation procedures

4. Establishment of effective communication with personnel involved

5. Monitoring and treatment of sick horses

6. Release of quarantine restrictions and return to normal operations

The most important measure in the management of an outbreak is the early recognition and isolation of a horse or horses with a suspected infectious disease. This requires diligent surveillance and the willingness of the facility management to take decisive action early in the course of a potential outbreak. These measures will potentially halt or limit the spread of disease as well as provide important information regarding the potential disease source and mode of disease transmission, and will perhaps identify a potential reservoir for the disease. It is important to remember that the first horse to display clinical signs of disease is not necessarily the primary case because an outbreak may be initiated by a clinically unapparent shedder of the infectious agent. All horses with a fever of unknown origin should be considered contagious until proved otherwise. This is especially true when febrile horses have a history of recent travel or recent exposure to new groups of horses. A contagious disease should always be suspected when multiple horses within a group have a fever. Horses with signs of respiratory, gastrointestinal, or neurologic disease that are accompanied by or have a history of fever should also be considered to be potentially contagious. Outbreaks may be associated with both viral and bacterial pathogens. Viral pathogens most commonly associated with outbreaks of infectious disease in North America include equine influenza virus, equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1), equine infectious anemia, rotavirus, and vesicular stomatitis. Bacterial pathogens associated with outbreaks of disease include Streptococcus equi subsp equi and Salmonella spp.

Diagnosis

At the outset of an infectious disease outbreak, a tentative or syndromic diagnosis can often be made on the basis of history, disease progression, and clinical examination of the horses involved. This initial information often gives insight into the probable mode of disease transmission and directs the initial biocontainment procedures. However, a specific etiologic diagnosis cannot be made based on this information alone. For example, respiratory disease caused by EHV-1 infection can initially mimic disease caused by other viral or bacterial agents. The same can be said for neurologic as well as gastrointestinal signs that may be observed in outbreaks of infectious disease. Therefore it is imperative to pursue a specific diagnosis through laboratory testing. This information is critical to the overall management of an infectious disease outbreak. Laboratory testing techniques that enable rapid identification, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), are most useful for yielding an early preliminary diagnosis. The initial diagnosis should be verified by viral isolation or bacterial culture as indicated for the disease in question. Rising titers in paired serum samples may be useful to identify horses that were exposed but clinically unaffected during an outbreak. Histologic and cytologic examination of appropriate tissue and fluid samples may also be indicated. Appropriate selection of horses to be tested and timing of sample collection relative to the stage of disease are important considerations. For example, nasal shedding of S equi does not usually begin until 1 to 2 days after the onset of fever; therefore early PCR testing of nasal secretions may fail to detect S equi. Another example would be PCR testing for EHV-1 in a horse with signs of neurologic disease because nasal shedding and viremia may have stopped by the time neurologic signs develop. Appropriate collection procedures and transport media, as well as correct handling and shipping of specimens, are important considerations in the pursuit of an accurate diagnosis. After a tentative or final diagnosis is made, clinicians should familiarize themselves with the epidemiology and pathophysiology of the disease. It is essential to be familiar with the possible routes of pathogen transmission, timing and duration of pathogen shedding, and duration of pathogen persistence in the environment. Additionally, the various clinical manifestations of the disease, methods of treatment, and suitable disinfection protocols should be reviewed. Consultation with a specialist familiar with the disease of concern is recommended.

General Considerations Regarding the Establishment of Isolation and Quarantine Areas

Although the terms isolation and quarantine are often used interchangeably, isolation is the physical separation and confinement of horses that are suspected or known to have a contagious disease. Quarantine refers to the confinement of healthy horses that have been exposed to a contagious disease. At the onset of an outbreak of infectious disease, an attempt should be made to categorize all horses on the basis of disease status. The three designated groups should include clinically affected, healthy but exposed, and unexposed horses. These horse groups should be formed and segregated at the onset of the outbreak, and the groups adjusted as indicated throughout the course of the outbreak. Ideally, designated personnel would be assigned to care for each group. Isolation and quarantine procedures will vary considerably among facilities depending on the design of the facility, availability of separate areas for isolation, disease involved and its mode of transmission, available personnel to care for horses, and expense.

Clinically Affected Horses

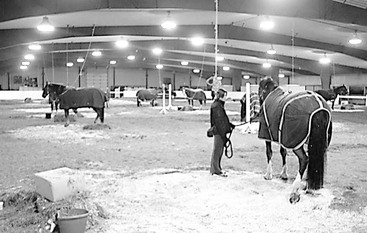

Horses with clinical signs of an infectious disease should be physically separated from unaffected horses and from other clinically affected horses, if possible. Ideally, these horses would be moved to a separate enclosure or barn at the facility. Other viable options include moving the horses to a remote facility that does not stable horses and using temporary enclosures such as portable tents and temporary stalls. The use of separate pastures is an option at some facilities, but should be discouraged in outbreaks that are caused by pathogens that persist for prolonged periods in the environment. If separate enclosures are not available for isolation of contagious horses or if available isolation areas become full, a portion or wing of the main facility may be used for isolation purposes. These areas should have as much physical separation as possible, such as empty stalls maintained between horses. Additionally, the isolation area should be clearly identified with barriers and signs to restrict traffic. Despite these measures, containment of an outbreak is difficult when horses affected with a contagious disease reside at the same facility as unaffected animals. In some situations, it may be more appropriate to quarantine the entire facility rather than attempting to isolate individual horses within the facility. This may be the best option when clinical cases are dispersed throughout all areas of the facility. A further consideration when developing isolation protocols is that the measures do not become so restrictive that they compromise the ability to monitor and care for the horses. Horses that require extensive care and therapy, such as horses that become recumbent during EHV-1 outbreaks or horses with colitis caused by Salmonella, are optimally referred to an equine hospital to receive the level of care required. Alternatively, a treatment area can be established within or on the grounds of the facility. Horses that require extensive care are relocated to this area for more efficient monitoring and treatment (Figure 31-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree