Chapter 73 Management of Cryptosporidiosis in a Hoofstock Contact Area

The nomenclature of this group has undergone numerous revisions and may be confusing. Cryptosporidium parvum remains the most common cause of zoonotic infections and cattle are its principal host species.5 Young calves, frequently animals younger than 8 weeks old, have been the source of almost all zoonotic cases of cryptosporidiosis involving direct animal contact. Numerous other species may be infected with C. parvum, including other domestic ruminants, pigs, and camels. Clinical cryptosporidiosis may occur in kids and lambs, and lambs have been linked to zoonotic cases as well. Adult cattle, sheep, and goats are infrequently identified as sources of zoonotic infections, and adult cattle may shed other nonzoonotic cryptosporidial species, such as C. andersoni.6

Clinical cryptosporidiosis occurs most commonly in neonatal and young animals. It has been estimated that more than 90% of dairies have infected stock.5 Signs in calves vary from unformed stool to severe diarrhea. Mortality is considered moderate for uncomplicated infections, but coinfection with other enteric pathogens or accompanying stress (e.g., from cold weather or transport) may increase morbidity and mortality. There is no generally accepted, specific treatment for cryptosporidiosis in North America. Paromomycin has been used for the treatment of individual animals4 and halofuginone is registered for the prevention and treatment of calf cryptosporidiosis in Europe.2

Cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent people is typically a self-limiting gastroenteritis. It may occur in any older adult, but children younger than 2 years are most frequently and severely affected. Signs in humans include watery diarrhea that may contain mucus and be accompanied by abdominal pain and bloating. Signs typically are gone within 3 weeks, but shedding of oocysts may persist for a short time after signs abate. In immunocompromised individuals, cryptosporidiosis may be a severe and debilitating disease. Involvement of the pancreatic duct and gallbladder tree may occur, in addition to intractable diarrhea. Chronic diarrhea, cholera-like symptoms, and severe weight loss are predominant signs in the profoundly immunocompromised individual.3

Diagnosis

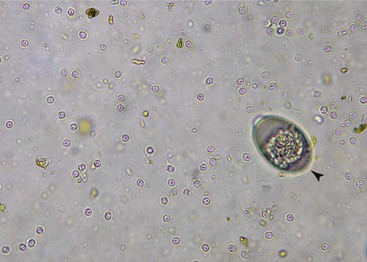

Cryptosporidium spp. are tiny organisms (4.0 to 6.0 mm in diameter), and many laboratories use special techniques for their identification in fecal samples. There is disagreement on which test is the gold standard, but most agree that visualization of oocysts is confirmatory. Concentration techniques such as a centrifugal flotation technique using Sheather’s sugar may be used (Fig. 73-1). Acid-fast staining of fecal smears or the use of auramine phenol fluorescent stains have been recommended. Many laboratories prefer immunofluorescent assays to sugar flotation; however, in one study there was significant agreement between polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of Cryptosporidium parvum and the flotation technique.7 Young animals with diarrhea shed millions of oocysts, but oocyst shedding may be infrequent in asymptomatic animals. Multiple fecal examinations are required to ensure that an asymptomatic individual is not infected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree