Chapter 14 Mammals

The rabbit (Oryctolagus cunniculus)

Rabbits belong to the mammalian order Lagomorpha. They were originally classified with species such as rats, mice and hamsters as members of the order Rodentia because they all have chisel-shaped incisors that are open-rooted and continue to grow throughout the animal’s life. However, rabbits have two pairs of upper incisors while rodents have only one pair, leading to the reclassification of rabbits (and the related hares and pikas) as lagomorphs. Rabbits are burrowing herbivorous animals that live in large social groups. They are readily preyed upon by carnivores and much of their anatomy is adapted to sensing danger and making a rapid escape.

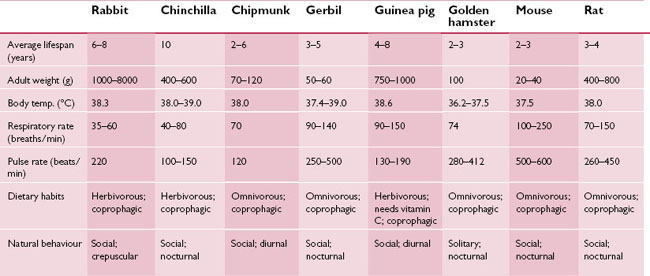

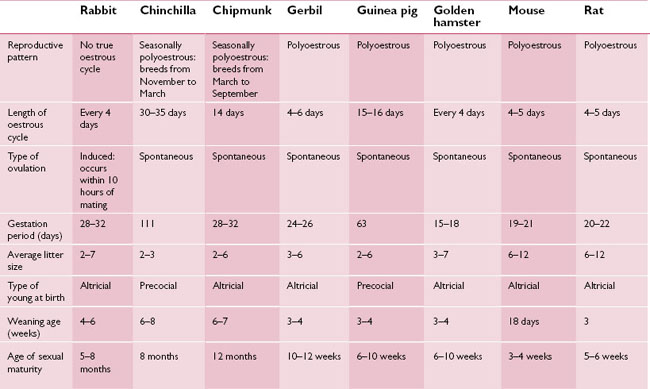

Tables 14.1 and 14.2 give physiological and reproductive parameters for rabbits.

Musculoskeletal system

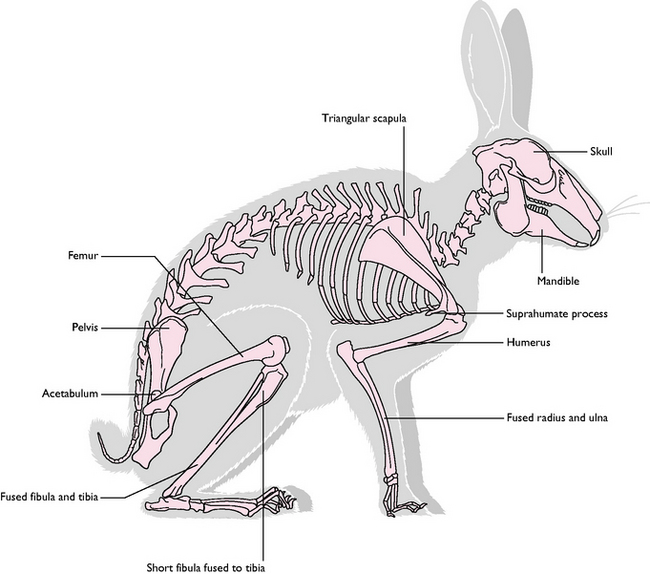

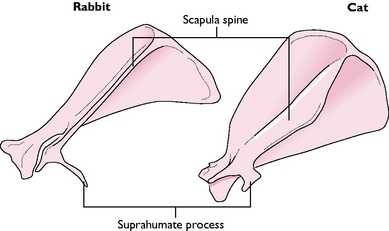

The skeleton of the rabbit (Fig. 14.1) is delicate and makes up only 7–8% of the body weight. This is in contrast to the skeleton of the cat, which makes up 12–13% of body weight. The cortex of the long bones is normally thinner than those of the cat and older caged rabbits may additionally develop osteoporosis from lack of exercise and low calcium intake.

The number of vertebrae in each part of the vertebral column is: C7, T12–13, L7, S4, Cd16.

There are a few differences between the skeleton of the rabbit and that of the cat:

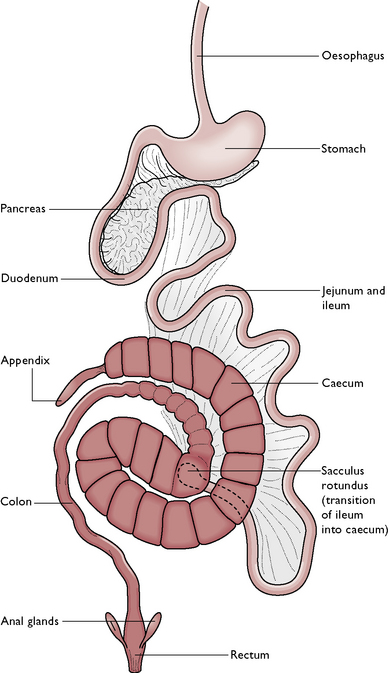

Digestive system

Rabbits are herbivorous and have been likened to ‘little horses’ in that both the rabbit and the horse are hindgut fermenters, i.e. the main chamber for the breakdown of plant material is part of the large intestine. Unlike the horse, however, the digestive system of the rabbit allows for rapid passage of food through the tract and rapid elimination of fibre. This has enabled the body size and weight of the rabbit to remain small, which allows the animal to show the speed and agility necessary to escape predators. By contrast, in the horse, fibre remains in the gut for some time, necessitating the evolution of a large-volumed fermentation chamber and consequently a large body size (see Ch. 16). The digestive tract of the rabbit (Fig. 14.3) is relatively long and makes up 10–20% of body weight.

Oral cavity

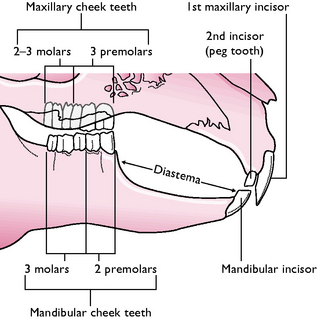

The opening of the mouth is small, the tongue is relatively large and the oral cavity is long and curved, making examination of the cheek teeth and intubation for anaesthesia difficult. All the teeth (Fig. 14.4) are open-rooted and grow continuously throughout life. They must be kept worn down by hard or fibrous food materials. The dental formula is:

If the teeth are misaligned or the diet does not include sufficient fibrous material, the teeth will not wear properly and the rabbit will suffer from a range of malocclusion problems (Fig. 14.5). Malocclusion is one of the most common reasons for rabbits being presented to vets but it can be prevented by including large quantities of good quality hay in the diet.

The incisors have enamel only on the outer surface, which wears more slowly than the inner surface, creating the characteristic chisel shape needed for nibbling plant material. In the upper jaw the second pair of incisors are vestigial pegs and lie behind the first pair. There are no canine teeth and the space between the incisors and the cheek teeth is known as the diastema. The premolars and molars – cheek teeth – are flattened table teeth for grinding food. The jaw moves in a circular fashion to force the food against their roughened surfaces. The lower teeth grow at a faster rate than the upper teeth.

Digestion

Rabbits are herbivorous, monogastric, hindgut fermenters. The ingested plant material passes down the tract by peristaltic contractions and undergoes enzymic digestion in the stomach and small intestine. The partially digested material enters the caecum, where it mixes with colonies of microorganisms responsible for the fermentation and breakdown of cellulose found within plant cell walls.

Reproductive system

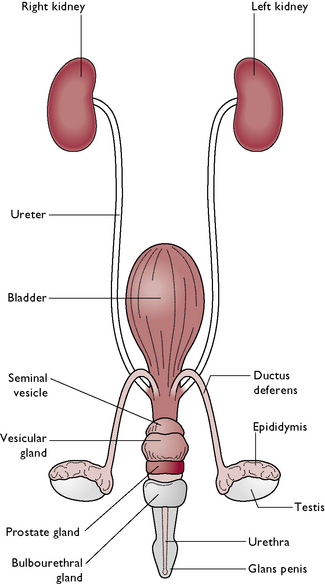

Male

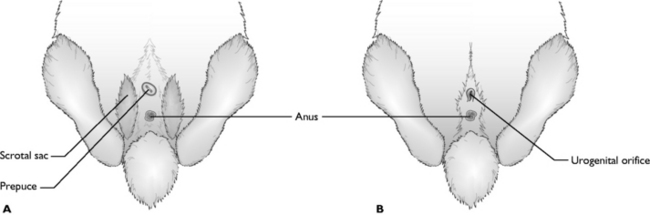

The male rabbit is known as a buck. There are two testes which in the adult male lie in two almost hairless scrotal sacs cranial to the penis (Fig. 14.6). The testes descend at about 12 weeks of age but the inguinal canal remains open; there is no os penis. The buck has no nipples.

Female

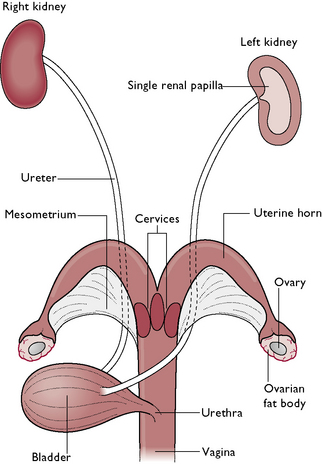

The female rabbit is known as a doe. The reproductive tract of the doe is bicornuate, i.e. it has two separate uterine horns designed to hold litters of young (Fig. 14.7). There is no uterine body and each horn has its own cervix opening into the vagina. The mesometrium is a major fat storage organ. The doe has four or five pairs of nipples.

Sexual differentiation

This can be difficult in young rabbits and is easier after the testes of the male descend into the scrotum (Fig. 14.8).

Fig. 14.8 Sexing a rabbit.

(With permission from O’Malley B 2005 Clinical anatomy and physiology of exotic species. Elsevier Saunders, Edinburgh.)