Chapter 24

Male Reproductive Tract

Prostate, Testes, Penis, and Semen

The most commonly evaluated organs of the male reproductive system are the prostate and the testes. Enlargement of either the prostate gland or testicle(s) and testicular tumors are the primary reasons for evaluation of these organs. Testicular fine-needle aspiration (FNA) may also be used to evaluate for male infertility concerns. While prostatic disease is frequently encountered in dogs, especially intact, older dogs, it is extremely rare in cats.1,2 Clinical signs that suggest enlargement of the prostate include difficulty with defecation or micturition, although difficulty with the latter occurs less frequently. Sometimes, urine is tinged red by blood, or blood or pus may drip from the penis. Males may also have decreased fertility or loss of libido. When any of these signs occurs, rectal palpation of the prostate may reveal symmetric or unilateral enlargement, focal bumpiness, or softness.3,4 Such prostate abnormalities detected by palpation or, occasionally, radiographic examination are the primary indications for obtaining material from the gland for cytologic evaluation. Testicular tumors rarely cause clinical signs, and enlargement of the testes or palpation of a mass on physical examination is the most common means for identifying testicular tumors. Aspiration of the testicle does not appear to have immediate or long-term adverse effects on male sexual performance or fertility.5,6 Penile and preputial cytology may also be helpful if a lesion is present, although limited published information is available.

Prostate Gland

Collecting and Preparing Samples

Material from the prostate may be obtained directly through the urethra or by FNA of the gland. To collect via the urethra, digitally massage the prostate while aspirating through a urinary catheter passed to the level of the gland.7,8 More prostatic material may be obtained by washing the part of the urethra near the prostate with a small amount of saline through gentle injection and aspiration while gently massaging the prostate. Material may also be obtained from the prostate through ejaculation.4,8 The prostate is gently massaged during the process to increase the amount of material of prostatic origin because this method may contain contaminants from other parts of the reproductive tract. The first part of the ejaculate contains material primarily derived from the prostate gland.4,8 The sample size is usually large and has a moderate concentration of cells. In addition to prostatic epithelial cells, ejaculated samples may contain numerous spermatozoa and other cells of reproductive tract and urethral origin. Simultaneously collecting and evaluating urethral wash specimens and urine samples (by antepubic cystocentesis) may alleviate some of the problems of interpreting the cytologic and microbiologic findings of the material collected by ejaculation.

The prostate may also be sampled by direct aspiration with a small-gauge needle. It should be noted that aspiration of the prostate is contraindicated when a prostatic abscess is suspected, as it is possible to seed the needle tract with organisms.1 Ultrasound-guided aspiration is superior to all other methods for obtaining specimens, especially from focal lesions such as cysts. The inguinal area is anesthetized, and the area is prepared as for surgery. Sterile petroleum jelly is applied to the skin to provide an acoustic coupler between the skin and the scanhead, and a small stab incision may be made in the skin to facilitate needle passage. While the ultrasound scanhead is held stationary and needle advancement is monitored on the screen, the needle is directed to the prostate or a specific location within the prostate. When the needle has reached the proper site, a small amount of specimen is aspirated into a sterile syringe.8

The prostate may be sampled by digital guidance of a needle as well, which may be passed through the posterior abdominal wall or the perineal region, although the latter method has not been widely used in veterinary medicine. At either site, local anesthesia is necessary to prevent discomfort and facilitate needle guidance. When the prostate is so enlarged that it can be palpated through the abdominal wall, the needle may be guided to the prostate while the dog is in either lateral or dorsal recumbency and the prostate is immobilized with one hand. This method is usually effective only when the prostate is markedly enlarged.8 From the perineal area, a finger is placed in the rectum, and the needle is passed through the skin in the perineal area and guided into the prostate along the finger. With both methods, the gland is gently aspirated while the needle is moved within it.8 Occasionally, only a small amount of material is obtained by aspiration, but it is usually adequate for making one or two direct smears.

Cytologic Evaluation of Normal Prostate

The cytologic features of the normal prostate vary, depending on the method of obtaining materials. Samples obtained by direct aspiration contain fewer contaminating cells and are usually more cellular than samples obtained from ejaculation, massage, or urethral washes. Glandular cells of the normal prostate are found in small to medium clusters, are uniform in size, cuboidal to columnar in shape and have a centrally to eccentrically located nucleus, which displays a finely stippled or reticular pattern. The cytoplasm has a fine, granular appearance and may be vacuolated (Figure 24-1, Figure 24-2, and Figure 24-3). If a prostatic wash was performed, a few contaminant bacteria may be present in association with squamous epithelial cells; however, in general, bacteria are not normally present in samples from the canine prostate gland. Cells and contaminating material from other locations in the urogenital tract may be found (Figure 24-4).

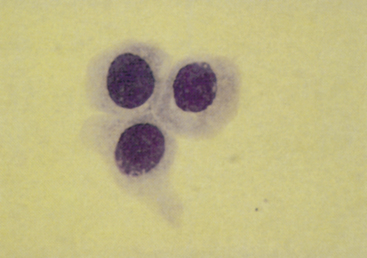

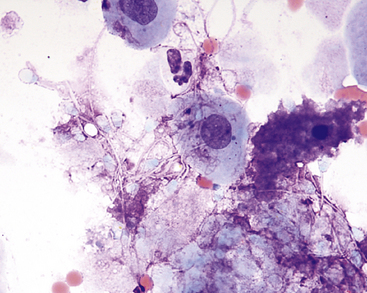

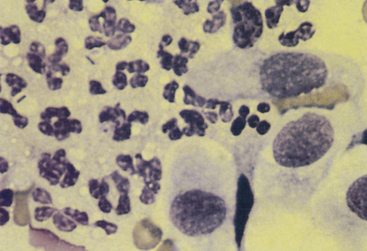

Figure 24-1 Epithelial cells from a normal prostate.

The cells are in large clusters and have mildly acidophilic cytoplasm and relatively large nuclei. Prostatic massage slightly concentrated by centrifugation. (Wright-Giemsa stain.)

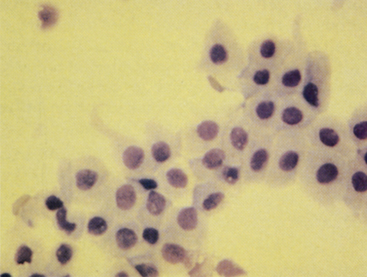

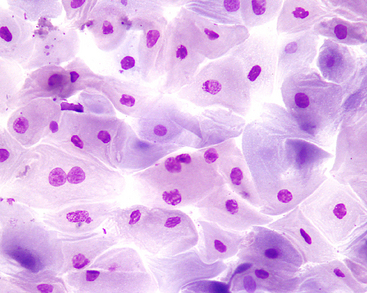

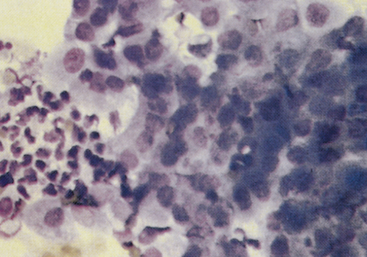

Figure 24-2 Epithelial cells from a normal prostate.

The cytoplasm is grainy and acidophilic, and the nuclei are centrally located and have a moderately reticular chromatin network. Prostatic massage slightly concentrated by centrifugation. (Wright-Giemsa stain.)

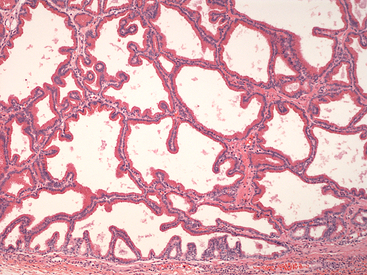

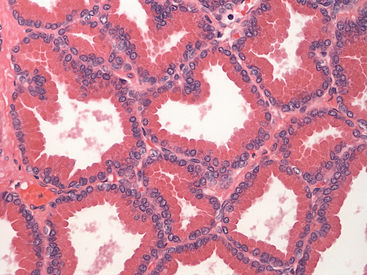

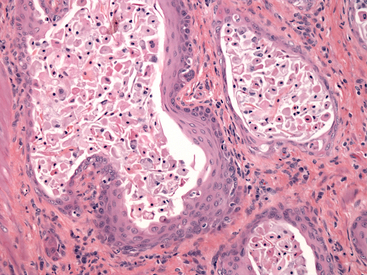

Figure 24-3 Histology of normal prostate.

Uniform cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells with apical eosinophilic cytoplasm are forming single-layered tubular structures. (H&E stain. Original magnification 400×.) (Courtesy of Dr. John Edwards.)

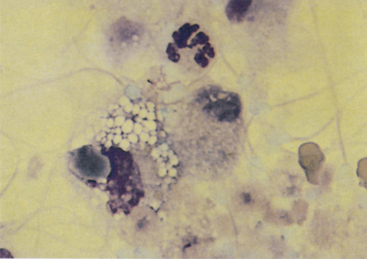

Figure 24-4 Prostatic wash from a normal dog.

Many spermatozoa, few epithelial cells, and a small amount of blood (few red blood cells and rare neutrophils) are present. (Wright-Giemsa stain. Original magnification 1000×.) (Courtesy of Dr. Rick Cowell.)

Spermatozoa

Sperm heads characteristically stain aqua with the Wright method. Spermatozoa, which often adhere to other cells, possibly with many attached to a single epithelial cell, are most frequently found in ejaculated material but may also be found in massage or wash samples (see Figure 24-4; Figure 24-5).

Figure 24-5 A prostatic epithelial cell, neutrophil, macrophage, and many spermatozoa from a dog with mild prostatitis.

The background contains proteinaceous material, which is probably the product of prostatic epithelial cells. Spermatozoa characteristically stain aqua with Wright stain. Prostatic ejaculate slightly concentrated by centrifugation. (Wright-Giemsa stain.)

Squamous Cells

Squamous epithelial cells are large cells with a flattened, floppy appearance. More differentiated squamous cells have a pyknotic or karyorrhectic nucleus, and immature squamous cells are difficult to differentiate from urothelial cells and possibly even prostatic epithelial cells. Because they originate from the distal urethra or the external genitalia, squamous cells are found not only in ejaculate, massage, and wash samples but also in prostatic squamous metaplasia (Figure 24-6 and Figure 24-7). Large, flat, and angular or rolled squamous particles may be obtained from the external skin surface as well; these particles do not usually contain even a remnant of a nucleus. Contamination by such particles may be nearly eliminated by cleaning the skin before obtaining a sample.

Figure 24-6 Squamous metaplasia of the prostatic epithelium in a dog with a Sertoli-cell tumor.

The cells are large and pale-staining, and some contain karyorrhectic nuclei. Prostatic massage concentrated by centrifugation. (Wright-Giemsa stain. Original magnification 500×.) (Courtesy of Dr. Rick Cowell.)

Figure 24-7 Histology of the prostate of a dog with squamous metaplasia caused by a Sertoli cell tumor.

Glandular epithelium has been replaced by a stratified squamous epithelium, and numerous sloughed squamous cells are present within the lumens. Note increased connective tissue between acini. (H&E stain. Original magnification 200×.) (Courtesy of Dr. John Edwards.)

Urothelial Cells

Urothelial cells (i.e., transitional epithelial cells) usually appear individually but may also be present in small clusters. They are larger than prostatic epithelial cells and have homogeneous, lightly basophilic cytoplasm and a lower nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N:C) ratio than prostatic cells (see Figure 23-1). Urothelial cells originate from the bladder and the tubular structures of the urinary and genital tracts and are most frequently found in samples obtained by ejaculation, massage, and washing.

Other Epithelial Cells

Cells of the ductus deferens and the epididymis are difficult to distinguish from prostatic cells.

Prostatic Cysts

Prostatic cysts may be present as incidental findings but are often present in dogs with concurrent benign prostatic hyperplasia or other prostatic diseases.1,9 A paraprostatic cyst has been reported in a cat.2 Prostatic cysts are quite variable cytologically. Some contain poorly cellular serosanguinous to brown fluid, which, even when concentrated, contains only a few epithelial cells, rare neutrophils, and some debris. Sometimes, moderate numbers of normal or slightly hyperplastic (e.g., basophilic) epithelial cells are found. Squamous cells are rarely obtained. The protein concentration of prostatic cysts is usually similar to transudate fluid.

Prostatitis

Bacterial prostatitis is the most common prostatic disease diagnosed in intact dogs.2,10 It occurs as either an acute infection or a chronic infection. Cytologic evaluation reveals predominantly suppurative inflammation. In septic prostatitis, the neutrophils typically have features that indicate degenerative change, including karyolysis and foamy cytoplasm (Figure 24-8). Usually, variable numbers of macrophages exist, especially in chronic prostatitis, which typically have abundant, foamy cytoplasm. Bacteria may be found both intracellularly and extracellularly, and when they are found, it is necessary to determine whether they are actually the cause of the inflammation or are contaminants from other locations in the genital or urinary tract.7 If the sample was obtained by an aspiration technique, the bacteria should be considered the cause, but if the sample was obtained through the urogenital ductal system, it is necessary to determine if the bacteria are contaminants from the external genitalia or from an inflammatory lesion elsewhere in the urinary or genital system. Intracellular bacteria are certainly a strong indication that the inflammatory process is septic. Organisms frequently isolated include Escherichia coli (most common), Proteus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Brucella canis, Mycoplasma spp., and Streptococcus spp. Fungal causes of prostatitis are infrequent but have been reported.1,11 In addition to inflammatory cells, clusters of variably-sized epithelial cells may be obtained. In aspirates obtained from an inflamed prostate, prostatic cells appear to have loose cohesion. Additionally, their cytoplasm usually shows increased basophilia, indicating that the prostatic epithelium is hyperplastic secondary to the inflammation (Figure 24-9).

Figure 24-8 Neutrophils and prostatic epithelial cells from a dog with acute prostatitis.

Bacilli are in some of the neutrophils, which are mildly degenerative with acidophilic, foamy cytoplasm and minimal nuclear degeneration. Prostatic massage slightly concentrated by centrifugation. (Wright-Giemsa stain.)

Figure 24-9 Hyperplasia of the prostatic epithelium from a dog with prostatitis.

The cells are basophilic and have an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio. Pleomorphism is minimal, and differentiation is suggested along the edges of the cell clusters. Prostate massage slightly concentrated by centrifugation. (Wright-Giemsa stain.)

Prostatic abscesses are focal areas of severe inflammation within the prostate, and they are a sequela to chronic prostatitis or prostatic cysts.1 Abscesses may be single, large accumulations of pus or multiple, small accumulations. Degenerated neutrophils with karyolysis and foamy cytoplasm present in a background of cellular debris are found. Features of prostatic hyperplasia may accompany prostatic abscesses. In addition to hyperplasia, the prostatic epithelium may also develop squamous metaplasia secondary to inflammation (see the discussion on squamous metaplasia later).

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a distinct entity that usually occurs in older, intact male dogs, and although the pathogenesis is not completely understood, it is apparently caused by a sex hormone imbalance.1,12 It includes both increases in cell number and cell size.1 Additionally, prostatic hyperplasia usually accompanies inflammatory lesions of the prostate, and the epithelium that lines prostatic cysts is often hyperplastic. Clinical signs associated with BPH are typically absent. However, enlargement of the gland may result in constipation, tenesmus, and stranguria. Mild hemorrhagic urethral discharge may also be seen. Prostatic palpation often reveals a symmetrically enlarged, nonpainful gland; however, an irregular surface or prostatic cysts may also be palpated. The cytologic features of the epithelial cells are similar regardless of the cause of the hyperplasia. Moderate cell numbers are usually found, often in variably sized clusters, although many individual cells are also found. In cell clusters, acinar-like arrangements may be seen, and cytoplasmic borders are usually indistinct. The cells are typically uniform and similar in appearance to normal prostatic epithelium. The cytoplasm is often abundant, basophilic, and slightly granular with or without small punctate vacuoles. Nuclei are round to oval and somewhat large, with finely reticulated or stippled chromatin patterns. Nucleoli are not usually observed. The N:C ratio is increased compared with that of normal prostatic cells (Figure 24-10 and Figure 24-11). When hyperplasia is not accompanied by inflammation, it should be considered a preneoplastic change.13

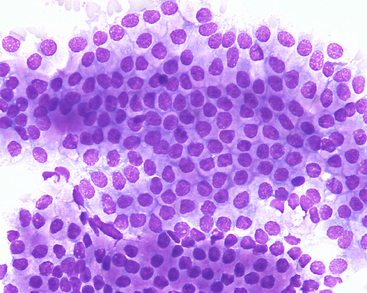

Figure 24-10 A large cluster of uniform prostatic epithelial cells from an older dog with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The cells have moderate amounts of purple granular cytoplasm that often contains vacuoles (fine-needle aspiration and biopsy). (Wright-Giemsa stain. Original magnification 500×.) (Courtesy of Dr. Rick Cowell.)

Squamous Metaplasia

Under the influence of the estrogen-like hormone activity that occurs with Sertoli cell tumors and rarely interstitial cell tumors, the epithelium of the prostate may undergo metaplasia to become a squamous-like epithelium (see Figures 24-6 and 24-7). Squamous metaplasia may also occur as a sequela to chronic irritation or inflammation, but the most prominent squamous metaplastic changes occur in dogs with Sertoli cell tumors or treated with exogenous estrogens.7,14 One case report in a cat described squamous metaplasia associated with interstitial cell neoplasia in a retained testicle, although hormone assays were not obtained.15 Aspirates are moderately cellular, and large cells (many individual, some in clusters) with slightly basophilic to slightly acidophilic cytoplasm are found. The cells are very large and appear flattened and floppy (see Figure 24-6). Cells occasionally contain a pyknotic or karyorrhectic nucleus. Inflammatory and hyperplastic prostatic epithelial cells are occasionally found.

Prostatic Neoplasia

Although less frequent, prostatic neoplasia does occur in both dogs and cats. In dogs, carcinomas or adenocarcinomas of the prostate are most commonly diagnosed.1,16 Although no breed predilection exists, most affected dogs tend to be medium- to large-breed, and tumors may develop in both intact and neutered animals.1,16 Prostatic carcinomas or adenocarcinomas have rarely been reported in cats.2,17,18 Prostatomegaly and its accompanying signs occur in dogs with prostatic carcinomas. Most prostatic carcinomas arise from the urothelium or transitional epithelial cells instead of the glandular prostate.14 On rectal palpation, the prostate may be very large, irregular, and asymmetrical, and in some cases, it is very painful.1,3,13,16 Cats with prostatic neoplasia may present with clinical signs associated with lower urinary tract disease, obstruction, or both. Cellularity of a cytologic sample is moderate to marked, and criteria of malignancy may be prominent and include anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, nuclear enlargement and irregularity, and marked increases in the N:C ratio (Figure 24-12, Figure 24-13, and Figure 24-14). However, some carcinomas may demonstrate only mild cellular atypia (Figure 24-15). Nucleoli are often present and are usually small, single, and uniform, but sometimes large, irregular nucleoli are found. Cell membranes may be distinct in well-differentiated neoplasms but are indistinct in poorly differentiated tumors. Cell cohesion is often apparent, and acinar-like formation is rarely present within some of the cell clusters. It is difficult to distinguish prostatic carcinomas that arise from the transitional cells from those that arise from the glandular area of the prostate by cytologic examination. Both may contain occasional cytoplasmic aggregates of eosinophilic granular material characteristic of these tumors (see Figures 24-12 and 24-13). However, when acinar-like structures are found, adenocarcinomas are more likely than transitional cell carcinomas.

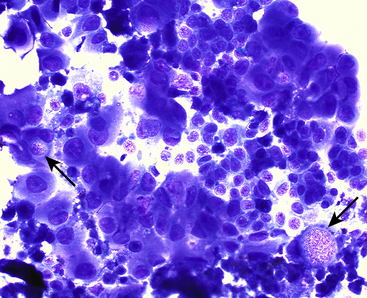

Figure 24-12 Clusters of neoplastic epithelial cells demonstrating marked criteria of malignancy.

Note the occasional intracellular vacuoles containing pink granular material, typical of prostatic and transitional cell carcinomas (arrows) (fine-needle aspiration and biopsy). (Wright-Giemsa stain. Original magnification 500×.) (Courtesy of Dr. Amy Valenciano.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree