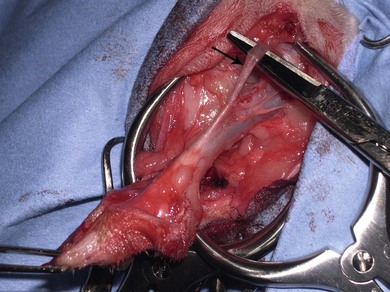

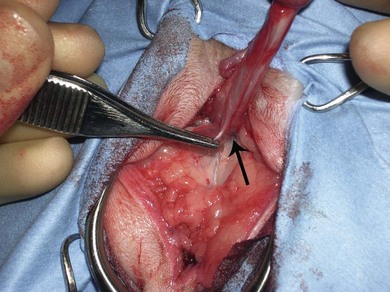

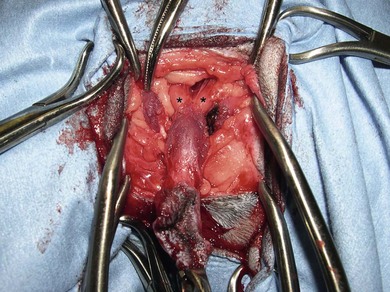

Chapter 39 Conditions of the male feline genital tract are rare, but include cryptorchidism and neoplasia of the testicles, intersex abnormalities of the penis, and rare reports of neoplasia of the testes. Urethral conditions by contrast are very common in the cat and these are covered in detail in Chapter 38. The male genital tract of the cat is comprised of similar components to the canine genital tract,1 but with some specific differences. The scrotum is covered with hair and situated just ventral to the anus, and the penis is directed caudally and the preputial orifice is positioned more dorsally than it is in the dog. The prepuce is comparatively short, and with a narrow preputial orifice that makes extrusion of the penis very difficult in the conscious cat. The urethral orifice is small and present on the tapered tip of the glans. It can become obscured in some clinical situations that cause inflammation (such as obstructive disorders associated with feline lower urinary tract disease). The entire adult cat has numerous short horny spines on the glans part of the penis that are often noted but have no clinical significance (Fig. 39-1). In the cat, there is a short length (3–5 cm) of preprostatic urethra.2 The prostatic urethra is 1.5–1.9 cm in length; the postprostatic urethra in the region of the caudal pubis is the widest (and longest) part of the feline male urethra. The preprostatic urethral wall contains three layers of smooth muscle, which gradually disappear in the prostatic urethra to be replaced further caudally by increasing amounts of striated muscle.2 This has significance when pharmacologic control of urethral relaxation is required. There is a delicate urethral mucosa (with transitional cell epithelium) that is more easily traumatized than in the dog because of the narrow urethral lumen. The bulbourethral glands are paired, pea-size pale yellow glands situated dorsolateral to the postprostatic urethra (Fig. 39-2). Paired ischiocavernosus/ischiourethralis muscles are present just distal to these glands and are highly vascular. Running along the dorsal surface of the penis at this level is the retractor penis muscle (Fig. 39-3), which is sometimes firmly attached to the penis, and on the ventral surface there is the ventral penile ligament (Fig. 39-4). Figure 39-2 Dissection of the urethra during perineal urethrostomy. The paired bulbourethral glands are visible just proximal to the incised ischiocavernosus muscles. Congenital disorders of the scrotum and testis are uncommon, and if present are often associated with disorders of other parts of the urogenital tract. Aplasia of the testes has been described,3 along with other anomalies such as a urethral-scrotal fistula4 and non-fused scrotal pouches.5 Monorchism occurred in 0.1% of cats presenting for routine neutering in one case series.6 Acquired conditions of the testis are uncommon in clinical practice because most cats are castrated at a young age. There are a few reports of neoplasia in the literature.7–9 This is the most common congenital disorder, that accounted for 1.7% of male cats presenting for neutering in one case series,5 and 1.3% of cats in another.6 The testicle may be located anywhere along its embryonic pathway, from the region of the kidney to the internal inguinal ring (abdominal) or from the external inguinal ring to the base of the scrotum (inguinal). If both testes are affected, one study suggested an abdominal location was more likely,5 but an inguinal location would appear to be more common overall.6 Clinical signs may be related to ongoing hormonal influence from the testicle (mainly inappropriate urination and malodorous urine), but may be related to neoplastic transformation.3 Diagnosis is usually by history taking and physical examination. Identifying the location, however, can be difficult. In some cases, the testicle can be easily palpated in the inguinal area in the anesthetized cat. If the individual has a large inguinal fat reserve, however, this can be difficult, especially as the testicle is sometimes small and poorly developed (Fig. 39-5).11 Figure 39-5 Testicles removed from a cryptorchid cat. The right testicle in the picture was inguinal; it is small and poorly developed. If there is any doubt it should be submitted for histopathologic evaluation for definitive confirmation that it is a testicle. (Courtesy of Jon Hall.) Neoplasia of the testis is rare in the cat and there are few examples in the literature. Tumor types reported include interstitial cell tumor,7 Sertoli cell tumor8 and teratoma,9 although it would be reasonable to assume that malignant transformation of any cell type present in the testis could occur. Two of the reports are of neoplasia occurring in retained testicles, which may suggest this predisposes to malignancy, as it does in the dog. Thorough evaluation of the patient should be made when a testicular tumor is suspected, with staging of the tumor being of paramount importance. Left and right lateral chest radiographs should be taken, and abdominal ultrasound used to examine the sublumbar lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. The surgery required for most histological types is simple castration (i.e., excisional biopsy) although removing the scrotal skin is recommended if the testicle is adherent to the overlying tissue. It is impossible to assess prognosis given the few cases reported. Congenital conditions of the penis and prepuce are occasionally seen in the cat. There are reports in the literature of hypospadias,12 phimosis,13 and intersex disorders.5 Hypospadia is a failure of embryonic fusion of the embryonic folds, leaving a defect in the ventral tissue of the penis and urethra; it has been reported as a cause of chronic cystitis in a pure breed cat.12 Phimosis is the inability to extrude the penis beyond the preputial orifice, and has been reported as a congenital defect causing hematuria and pollakiuria in a domestic short-hair cat;13 stranguria and pollakiuria were reported as the most common clinical signs in a series of ten cats with phimosis. Clinical signs resolved when surgery was performed to widen the preputial orifice.14 Intersex diseases have also been uncommonly reported: in one case a pure breed cat showing no clinical signs had a genital cleft rather than a true prepuce or vulva, with a large clitoris with horny spines similar to those on a normal penis. There were no chromosomal abnormalities found and so a diagnosis of pseudohermaphroditism was made.4 In any congenital disease of the urogenital tract, surgical intervention is indicated only if functional disease results, such as dysuria or predisposition to urinary tract infections. The extent of the disease often means that surgical intervention is difficult and may not bring much benefit for the animal. Balanoposthitis was reported in an entire male cat that presented with incontinence and preputial swelling; postmortem examination revealed the presence of chronic pyelonephritis and prostatitis.15 Acquired diseases of the penis are uncommon, and more often relate to diseases of the urethra rather than being specific to the penis (see Chapter 38). Management is mainly aimed at maintaining or restoring urethral function to allow urination. Preputial skin can develop neoplasms of the same type as any area of skin.

Male genital tract

Surgical anatomy

Surgical disorders of the scrotum and testis

Cryptorchidism

Neoplasia

Surgical disorders of the penis and prepuce

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree