Chapter 50Lumbosacral and Pelvic Injuries in Sports and Pleasure Horses

Anatomical Considerations

Detailed anatomy of the ilium, ischium, pubis, sacrum, coxofemoral joint, sacroiliac joints, nerves, and major vessels is described elsewhere (see Chapters 49, page 564, and 51, page 583). The lumbosacral joint comprises five separate joints: the intercentral joint between the caudal aspect of the vertebral body of the sixth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum, between which is an intervertebral disk; two intertransverse joints; and two synovial intervertebral articulations between the articular processes of the sixth lumbar vertebra and the cranial articular processes of the sacrum. Movement is principally restricted to flexion and extension because of the large transverse processes.1 Congenital variations in anatomy can be seen, including fusion of the fifth and sixth lumbar vertebrae or sacralization of the sixth lumbar vertebra resulting in lumbosacral ankylosis. These result in stress concentration on adjacent joints. The biomechanical stresses of movement of the lumbosacral joint place particular compression and traction forces on the intervertebral disk, which may predispose to disk degeneration.

Clinical Signs

Clinical Examination

Ridden exercise is invaluable in horses with a history of poor performance, reduced hindlimb impulsion, or low-grade lameness because frequently the lameness or restriction in hindlimb gait is accentuated. This may be most obvious in deep footing. Some horses with sacroiliac joint region pain or lumbosacral region pain show extreme reluctance to go forward freely. Affected horses may feel to the rider much worse than they appear to a trained observer. However, care must be taken to differentiate these horses from those with bilateral hindlimb lameness, thoracolumbar pain, or recurrent low-grade exertional rhabdomyolysis and those performing poorly because of the rider (see Chapter 97), previous poor schooling, or a combination of boredom and an unwilling temperament.

Analgesic Techniques

In horses with chronic lameness, reduced hindlimb impulsion, or poor performance, excluding the distal aspect of the limb as a source of pain by performing perineural analgesia of the fibular and tibial nerves and intraarticular analgesia of the three compartments of the stifle joint may first be necessary. If the response is negative, intraarticular analgesia of the coxofemoral joint may be indicated. This is relatively straightforward to perform if the horse is not well muscled and the greater trochanter of the femur is readily palpable. However, in the majority of heavily muscled, mature competition horses, needle placement must be guided by ultrasonography.4 Even if the needle is accurately positioned, retrieval of synovial fluid may be difficult. Extraarticular deposition of local anesthetic solution may result in transient paralysis of the obturator nerve and instability of the limb. The technique is described in Chapter 10.

Intraarticular injection of the sacroiliac joint cannot be achieved; however, infiltration of local anesthetic solution around the sacroiliac joint region may result in dramatic clinical improvement, presumably by alleviation of pain associated with the joint and periarticular structures. It cannot be considered an entirely specific technique and potentially could also influence pain from the lumbosacral joint and local nerve roots. The techniques are described on page 589. Infiltration of local anesthetic solution around the sacroiliac joint regions resulted in significant improvement in 95 of 108 horses with clinical signs suggestive of sacroiliac joint pain.5 Horses were reassessed ridden 15 minutes after injection. If local anesthetic solution is placed too far caudally there is the possibility of inducing sciatic nerve paralysis either unilaterally or bilaterally. In my experience, this is extremely rare (<2%), but if bilateral, the horse will become recumbent and may remain so for up to 3 hours before returning to normality.5

Diagnostic Imaging

Ultrasonography

Diagnostic ultrasonography is useful in evaluating fractures (see Chapter 49, page 564), assessing muscles (see Chapter 83) and the sacroiliac ligaments (see page 578), determining blood vessel patency (see page 581), assessing the lumbar vertebrae and articulations, and evaluating nerve roots.

Differential Diagnosis

Fractures

Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of fractures of the pelvis in the young Thoroughbred (TB) racehorse have been dealt with in depth (see Chapter 49), and this section focuses on differences in mature athletic horses. The incidence of stress or fatigue fractures of the pelvic region in the mature horse is low, except in horses that race over fences, which have a substantial incidence of ilial stress fractures. The clinical features are similar to those in the young racehorse (see Chapter 49), although there is a higher prevalence of horses with fractures extending into the ilial shaft that have a guarded prognosis. The majority of other fractures result from external trauma.

Tuber Ischium

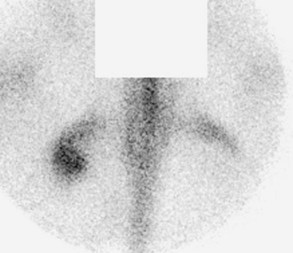

Diagnosis of a fracture of the tuber ischium can be confirmed using nuclear scintigraphy (Figure 50-1). Dorsal oblique and caudal images are useful. Usually increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU) and an abnormal pattern of uptake are apparent.16 In some horses determining whether the fracture is complete and whether it has become substantially displaced may be possible. It is important to recognize that IRU may persist for many years after injury, and therefore the results of scintigraphic examination must be carefully correlated with the results of clinical examination.19 Discontinuity of the bone outline may also be confirmed using diagnostic ultrasonography. Limited radiographic examination can be performed in a standing horse, but it is most easily and safely done with the horse under general anesthesia. Less commonly there is entheseous reaction with IRU in both the tuber ischium and the ipsilateral semimembranosus and/or semitendinosus muscles. Ultrasonographic examination may demonstrate irregularity of the tuber ischium and decreased or increased echogenicity of the injured muscles depending on the acuteness or chronicity of injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree