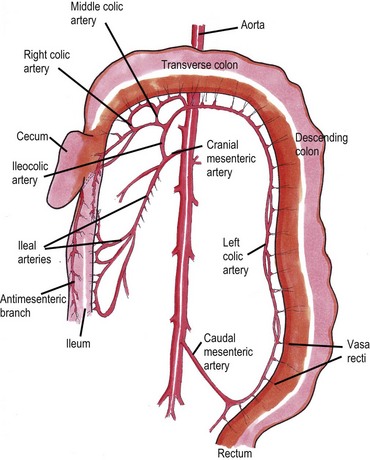

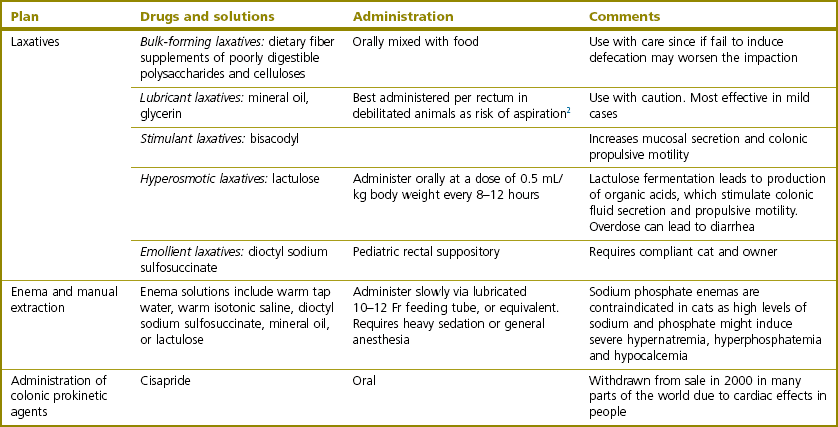

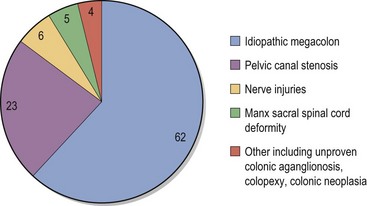

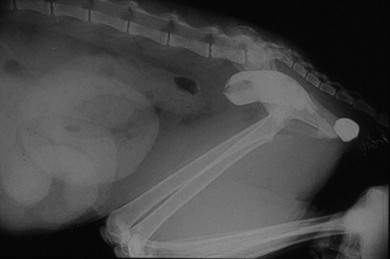

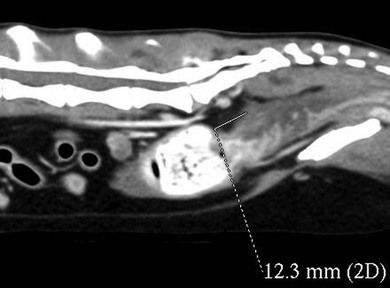

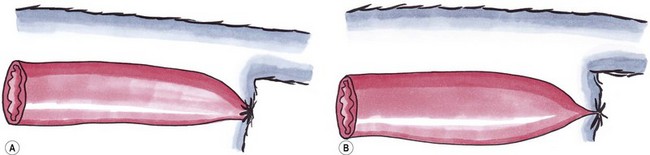

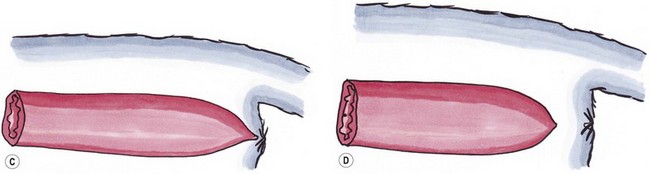

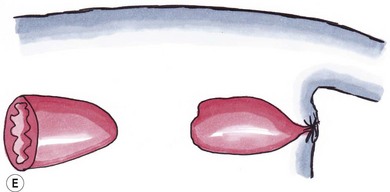

Chapter 30 In the normal individual, the total colonic length as a percentage of the intestinal length is remarkably constant at 20.9 ± 2.0%.1 The layers of the colon are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. Like the small bowel, it is the submucosal layer that is considered important in maintaining mechanical strength during the process of suturing or stapled closure and anastomosis. The large intestine obtains its arterial blood supply from branches of both the cranial mesenteric and caudal mesenteric arteries (Fig. 30-1). The ileocolic artery, a branch of the cranial mesenteric artery, supplies the ileum, cecum, and ascending and transverse colon. The ileocolic artery gives rise to the middle colic and right colic arteries. The middle colic artery supplies part of the transverse colon and half of the descending colon. The right colic artery supplies the cecum, the ascending colon, and part of the transverse colon. The left colic and cranial rectal arteries arise from the caudal mesenteric artery. The left colic artery supplies the distal half of the descending colon before anastomosing with the right colic artery. Vessels arising from the caudal mesenteric artery and passing in a caudal direction are considered to be supplying the rectum. The cranial rectal artery primarily supplies the cranial and caudal rectum. The caudal rectum also receives a supply from vessels arising from the internal iliac artery via the prostatic or vaginal arteries. Presenting signs of cats with colorectal disease will often typify the condition encountered such as the constipation associated with megacolon and the complete lack of defecation in individuals suffering from atresia ani. Constipation has been defined as infrequent or difficult defecation associated with the retention of feces within the colon and rectum.2 Obstipation is a condition of prolonged and intractable constipation resulting in severe fecal impaction throughout the rectum and colon. Obstipated animals are unable to eliminate the impacted fecal material. Dyschezia describes difficult or painful evacuation of feces from the rectum. This clinical sign is commonly associated with lesions in or near the anal region. Alimentary tenesmus is the clinical sign that characterizes an animal that strains to defecate. The straining is often painful and ineffectual. Alimentary tenesmus is commonly associated with disease of the large intestine and lower intestinal tract. The content, position and size of the large intestine may be variable. The width of the normal feces-filled colon should not be greater than three times the width of the small intestines or the length of the seventh lumbar vertebra. Enlargement of the diameter of the colon beyond 1.5 times the length of the seventh lumbar vertebra is indicative of chronic large bowel dysfunction and megacolon.4 The normal colonic wall may have a corrugated appearance (due to peristalsis) and this finding should not be interpreted as abnormal unless it is a consistent finding on subsequent, serial radiographs. Colonoscopy and proctoscopy will, in general, be performed with a flexible endoscope in the cat. Such an endoscope should have a biopsy channel so that suitable lesions can be sampled at the time of the procedure. The importance of correct bowel preparation cannot be over-emphasized. Preparation will normally include a period of 24–48 hours of starvation with the administration of some form of enema (possibly on more than one occasion) prior to the study. To be performed safely, the procedure will require a full general anesthetic. Inadequate cleansing of the large bowel will produce unsatisfactory and meaningless findings at the time of the endoscopy. Difficulty in achieving adequate and safe cleansing of the bowel in the cat has led to a reluctance to perform the procedure in the species. This is unfortunate since the large bowel is very accessible for a complete endoscopic examination and the procedure will frequently provide a definitive diagnosis without recourse to surgery. Indications for colonoscopy include dyschezia, tenesmus, constipation, or chronic diarrhea containing mucus and/or fresh blood. For more information see Chapter 9. Megacolon is a descriptive term only, and its use imparts no information regarding specific etiology or pathophysiology. The condition should be considered a disorder characterized by recurrent constipation and/or obstipation associated with dilatation and hypomotility of the colon. Often the underlying etiology for the condition remains unknown and in many cases it is more appropriate to define the mechanism by which the condition developed. The common two pathologic mechanisms are either dilatation or hypertrophy.7 In humans, a congenital form of megacolon (Hirshsprung disease) is well recognized. It occurs in neonates and is characterized by aganglionosis of a segment of colon, resulting in the persistent contraction of smooth muscle within the affected segment and the subsequent dilatation of the colon proximal to the constricted, affected site. This condition has been suggested to occur in cats,8 although its true existence in this species has only been documented in one case.9 In a review of 120 cases of megacolon in cats, 62% were accounted for by idiopathic megacolon, 23% demonstrated pelvic canal stenosis, 6% demonstrated nerve injuries, 5% showed Manx sacral spinal cord deformity, and the remaining 4% included unproven colonic aganglionosis, complications of colopexy, and colonic neoplasia (Fig. 30-2).10 It was concluded that although it remains true that megacolon may have an extensive list of differential diagnoses and may be associated with other disease processes including active colonic inflammation, dysautonomia, and metabolic disorders, the majority of cases are idiopathic, orthopedic, or neurologic in origin. Figure 30-2 Causes of megacolon. (From Washabau RJ, Hasler AH. Constipation, obstipation, and megacolon. In: August JR, editor. Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1997. p. 104–12.) A diagnosis of megacolon is made by estimation of the colon size on radiography. Enlargement of the diameter of the colon beyond 1.5 times the length of the body of the seventh lumbar vertebra is indicative of chronic large bowel dysfunction and megacolon.4 Megacolon is most commonly observed in middle-aged (mean 5.8 years) male cats (70% male, 30% female) cats. The domestic shorthair (46%) followed by the domestic longhair (15%) and Siamese (12%) are the breeds most commonly affected.10 Specific therapy depends on the severity of the constipation and the underlying cause for the condition. A summary of non-surgical management and the drugs that can be used is listed in Box 30-1 and Table 30-1. In the majority of cats with idiopathic megacolon, medical treatment using laxatives, enemas, and dietary management offers only a temporary relief of clinical signs. It is now widely accepted that colectomy should be considered in cats with the condition that is refractory to medical therapy. Several different surgical techniques for the management of the condition have been described and these include coloplasty,11,12 a partial colectomy,12–15 or the more complete or subtotal colectomy.8,16–20 The surgical management of idiopathic megacolon and constipation has been reviewed comprehensively.21 Causes of outlet obstruction causing secondary megacolon in the cat are listed in Box 30-2. Of these, the most common cause of outlet obstruction causing secondary megacolon is pelvic fracture malunion.22 Outlet obstruction will initially result in the development of a hypertrophic megacolon.32 Hypertrophic megacolon is often reversible with the early removal of the colonic outflow obstruction. If left untreated, the obstruction will result in progression of the condition to an irreversible dilated megacolon. In general, therefore, prompt treatment of outlet obstruction will involve removal of the underlying cause of the obstruction. A major complication in cases that have already developed dilated megacolon is the continued dysfunction of the colon following the removal of the outlet obstruction. In such instances, continued problems with constipation/obstipation may be managed medically. In cases that are unresponsive to medical management, a subtotal colectomy should be considered. Complications after surgery for megacolon include diarrhea from short bowel syndrome (see Chapter 29) and peritonitis from dehiscence of the anastomosis (see Chapter 26). In the long term, the most common complication is recurrence of the constipation. In the majority of such affected individuals, the constipation can be treated by dietary management, stool softeners, and the occasional manual removal of feces, until a satisfactory medical regime for the management of the constipation is developed.7 Affected individuals should be carefully assessed to ensure that there is no evidence of either outlet obstruction or megarectum (see section below) that might cause ongoing issues with distal physical or functional bowel obstruction. It might be expected that recurrent constipation would be a more common complication in individuals in which the ileocolic junction was retained at the time of colectomy. In these individuals, the retained colonic segment is likely to be larger than in those individuals in which the junction was resected and an enterocolostomy was performed. In fact, studies suggest that there is no significant difference in the rate of recurrent constipation between the two surgical procedures of colocolostomy and enterocolostomy.20 The development of constipation or obstipation is a rare complication following routine ovariohysterectomy or castration in the cat.23–27 In all the reported cases the constipation/obstipation was associated with an extrapelvic, extraluminal stricture of the colon situated just cranial to the pelvic brim (Fig. 30-3). Figure 30-3 A 1-year-old cat presented with an inability to defecate eight weeks after ovariohysterectomy. Stenosis at the rectocolic junction is demonstrated after administering a barium enema. In queens, the complication becomes manifest within ten weeks of the ovariohysterectomy. The cause of the stricture is either a collar of residual uterine horn tissue that forms adhesions with the mesocolon or a ring of non-adherent fibrous tissue, the origin of which remains unclear. Surgical resection of the offending tissues and fibrous adhesions appears to result in the long-term resolution of the obstructive clinical signs without the necessity to perform a subsequent subtotal colectomy.24–26 It has been suggested that the risk of this complication may be reduced by ensuring that the uterus is amputated at, or as close to, the cervix as possible during the ovariohysterectomy procedure.24,25 A similar condition has been reported in the tom.27 In this instance, an open castration had been performed and clinical signs of constipation and fecal tenesmus developed eight weeks after the surgery. The cause of the stricture was found to be a non-adherent fibrous ring encircling the distal descending colon. The origin of the fibrous band was unclear, but it was considered possible that retraction of the spermatic cord following an open castration may, especially if the procedure was performed without adequate asepsis, result in the formation of a fibrous ring around the descending colon. As with the female cats following ovariohysterectomy, removal of the offending tissue resulted in the long-term resolution of the clinical signs. Perineal herniation is not as commonly diagnosed in the cat as in the dog, but in affected individuals the condition may induce fecal impaction, constipation, and obstipation.28 Obstipated individuals may go on to develop a secondary dilated megacolon. Surgical repair of the hernia or hernias (see Chapter 25) will alleviate the constipation in the majority of individuals. Cats with any degree of fecal colonic impaction should have the impacted feces removed prior to, or at the time of, hernia repair. In individuals in which fecal impaction recurs, a careful assessment of the repairs and/or assessment of a previously unaffected side should be performed to rule out the presence of further hernia development. If it is concluded that no further perineal herniation is present, but the animal is suffering from megacolon, a subtotal colectomy should be considered, since further straining associated with the fecal impaction/megacolon is likely to result in a breakdown of the herniorrhaphy repair. Therefore, the early removal of the diseased colon is to be recommended. In fact, it has been suggested that in individuals suffering from both perineal herniation and a secondary dilated megacolon, the removal of the megacolon alone may relieve the clinical signs, making concurrent perineal hernia repair unnecessary.32 In cats, the most common large intestinal tumor is adenocarcinoma, followed by lymphoma and mast cell tumor.33 In the largest case series of cats with tumors of the colon, the mean age at presentation was 12.5 years, 46% of the tumors were adenocarcinoma, 41% were lymphoma, and 9% were mast cell tumors.34 Clinical signs often include constipation, fecal tenesmus, diarrhea, anorexia, and weight loss.35 Clinical examination will often confirm the presence of a caudal abdominal mass on abdominal palpation. Further investigations should include full blood analyses (including testing for feline leukemia and immunodeficiency viruses), imaging of the abdomen (survey radiographs, abdominal ultrasonography, contrast enhanced CT scan, etc.), and protoscopy/colonoscopy (to allow visualization and biopsy) (Fig. 30-4). In cases with cancer, the disease should be staged with thoracic radiography/CT and ultrasonography/CT imaging of the liver, spleen, and local lymph nodes.36 Figure 30-4 CT scan of a colorectal adenocarcinoma causing stenosis of the large bowel at the colorectal junction. Treatment, in most instances, is the surgical excision of the mass followed by end-to-end anastomosis via a ventral midline celiotomy. Obtaining clean margins at the time of excision will, not surprisingly, increase survival time. Conversely, gross evidence of local or distant metastasis at the time of surgery will lead to a decrease in survival time. Margins of excision have been suggested to be at least 2.5 cm and, ideally, up to 5 cm from each end of the mass.37 For tumors at the colorectal junction, it will often prove impossible to achieve such margins on the rectal side of the growth, making local recurrence at the site a real possibility. Access to the intrapelvic rectum can be improved by performing either a midline pubic symphysiotomy/symphysectomy with or without an ischial osteotomy.38 Cats suffering from adenocarcinoma are very likely to have metastatic disease at the time of presentation; in one study about 80% of cats with this colonic tumor had metastasis (local or distant) at the time of surgery.34 Cats with negative lymph nodes at surgery lived a median of 259 days, versus 49 days if positive. Four cats with adenocarcinoma were treated with doxorubicin, and lived a median of 280 days, versus 56 days without.34 For cats with adenocarcinoma, there is some evidence to suggest that the excision of the mass should be combined with a subtotal colectomy. One study showed a mean survival time (MST) of 138 days in those cats undergoing mass excision and subtotal colectomy compared with a MST of 68 days in those in which only mass excision was performed.34 The reason for this difference in survival time remains unclear but may reflect the increased possibility of obtaining ‘clean’ margins. No such advantage was seen with additional subtotal colectomy in cats surgically managed for lymphoma. Despite this, the current recommendation in cats suffering from an unidentified colonic mass is that, as part of their surgical management, they should receive a subtotal colectomy to increase survival time. For large intestinal lymphoma, cats with surgery appear to fare equally poorly with or without adjunctive chemotherapy (MST of just over three months in both groups).39 There is little information available for the management of large intestinal mast cell tumor in the cat. In one study, in four cats with mast cell tumor, two had local metastasis; one distant and one local. All the cats were treated with surgery and prednisolone with a MST of 199 days.34 There is some evidence that cases with non-resectable colonic cancer might benefit from the placement of colonic stents as part of the management of their disease. Metal stents placed under fluoroscopy were palliative in two cats with colonic adenocarcinoma, one for 274 days (with good quality of life and euthanasia due to eventual distant metastasis) and one for only 19 days (euthanasia due to perceived reduction in quality of life).40 Cats with certain forms of colonic cancer may benefit from radiation therapy (see Chapter 15) of the local disease, but there are no reports describing its use for this disease at the present time. Atresia coli describes a segmental intestinal anomaly affecting a portion of the colon. The anomaly is characterized by the absence or closure of a segment of colon. Congenital atresia develops when areas of the intestine either fail to vascularize or the blood vessels degenerate early in development. Causes of the condition in domestic animals and humans include fetal enteritis, peritonitis, anomalies or diseases of the fetal blood vessels, and injuries sustained in utero by a previously normal fetus.41,42 Although the condition is considered the most common segmental anomaly of the intestine in domestic animals, it has only rarely been described in the cat.31,41 Four types of atresia ani have been reported (Fig. 30-5 and Table 30-2). Table 30-2 Types of atresia ani in the cat Figure 30-5 Atresia ani in the cat. (A) Normal cat, (B) type I, (C) type II, (D) type III (E), type IV. Clinical signs of atresia ani usually begin within a few weeks of birth. Cats with congenital stenosis (type I) will usually develop constipation and tenesmus soon after weaning. Cats with types II, III, and IV atresia ani usually have perineal swelling or anal membrane protrusion from accumulation of meconium and feces within the rectum. Other findings include abdominal distension, abdominal discomfort and an absence of defecation. If obstruction is longstanding, vomiting and dehydration can develop. Individuals with atresia ani may have multiple congenital anomalies and, therefore, should be fully examined with care before any form of surgical correction is considered. A number of concurrent congenital and acquired lesions have been reported in conjunction with atresia ani in the cat, the three most recognized are listed in Box 30-3.

Large intestine, rectum and anus

Surgical anatomy

Diagnosis and general considerations

Definitions

Diagnostic imaging for intestinal disease

Plain radiography and contrast radiography3

Colonoscopy/proctoscopy6

Surgical conditions of the large intestine and anus

Megacolon

Colonic entrapment following ovariohysterectomy or castration

Constipation associated with perineal herniation

Neoplasia of the colon

Atresia coli

Surgical conditions of the rectum and anus

Atresia ani

Type I

Congenital stenosis of the anus

Type II

Imperforate anus; characterized by persistence of the anal membrane with the rectum ending blindly cranial to the imperforate anus

Type III

Imperforate anus combined with more cranial termination of the rectum as a blind pouch

Type IV

Discontinuity of the proximal rectum with normal anal and terminal rectal development

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine