Chapter 117Lameness in the Three Day Event Horse

Sport of Eventing

The sport of eventing generally is considered the most all-around test of a horse’s athletic ability, and therefore the horses tend to be jacks-of-all-trades rather than excelling in any one particular area. The competition consists of three disciplines, namely dressage, show jumping, and cross-country, with the latter being the most influential phase. The Three Day Event or Concours Complet International (CCI) is the pinnacle of the sport (Figure 117-1) and is run over 4 days: 2 days of dressage, followed by a day for the speed and endurance phases and a day of show jumping. In the traditional long-format event the speed and endurance test consists of roads and tracks at trotting speed, a steeplechase, and the actual cross-country phase over fixed obstacles. This is a severe athletic test, and horses normally compete in only two or maximally three such competitions in a year. Since 2004 a “short format” Three Day Event has been introduced, which excludes the steeplechase and endurance phases but leaves the cross-country phase. This is cheaper to stage and potentially requires a smaller site on which to run the competition. At CCI**** level the course must be 6720 to 6840 m in length, with up to 45 jumping efforts at an optimum speed of 570 mpm, to therefore be completed within 11 to 12 minutes. It has resulted in some horses competing in three or occasionally four such competitions in one year.

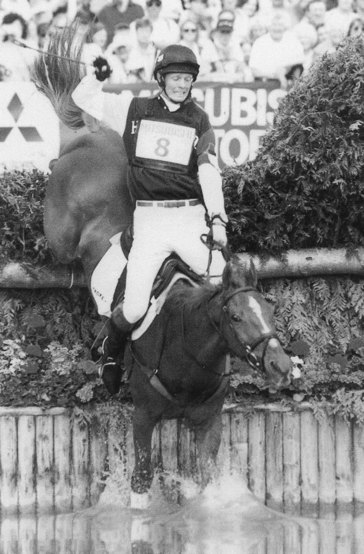

Fig. 117-1 Example of a cross-country fence at CCI**** level.

(Courtesy Kit Houghton Photography, Bridgewater, Somerset, United Kingdom.)

Horse Types

Because the Three Day Event places great emphasis on the horse’s speed and stamina, there is a preference toward the Thoroughbred (TB) or predominantly TB crossbreeds. A substantial proportion of horses are of uncertain or unknown breeding. Exceptions have been notable, but Warmbloods and classic Irish hunter types normally do not have the endurance required at the top level. Such horses often may do extremely well at the lower levels, however, because they move and jump better than the pure TB. Figure 117-2 demonstrates what could be considered the ideal modern eventing stamp, a highly successful New Zealand TB. A horse’s ability and mental aptitude are the most important determinants, and other body types are successful (Figure 117-3). An average ideal size would be 16.2 hands, but the rules are not hard and fast. The short-format Three Day Event has perhaps slightly reduced the emphasis on pure galloping ability, and because the courses usually have the same number of jumping efforts, sometimes in a shorter course, there is a need for the horses to be quick and nimble.

Clinical History

A routine lameness history should be obtained, emphasizing and obtaining the following information:

Lameness Examination

Different considerations apply when examining the horse with a history of an acute, severe lameness, usually after the cross-country phase of a competition. A comprehensive evaluation of an acutely lame horse must be performed (see Chapter 13) and is described in detail elsewhere.3 Unfortunately, localizing signs may be minimal, the horse may be in cardiovascular shock, and initial efforts must be directed at providing support to the horse and the suspected region of injury. Fractures are caused most commonly by external trauma. Particular attention should be paid to the shoulder region for signs of fracture of the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula and to the stifle for effusion or periarticular swelling associated with patellar or other fractures. Soft tissue injuries such as severe suspensory desmitis or superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonitis may cause acute, severe lameness.