Chapter 124Lameness in the Driving Horse

Description of the Sport

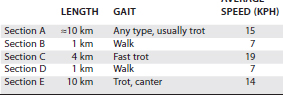

Horse driving trials consist of three phases—dressage, marathon, and cones—usually spread over 3 days, but in lower standard competition all three may take place over 1 to 2 days. The first phase is a driven dressage test, which consists of a set sequence of movements that are judged by a number of officials against a standard of absolute perfection. The test is designed to highlight the obedience, paces, and suppleness of the horse(s), and the skill of the driver in handling of the reins. The second stage is the marathon, which tests the fitness and stamina of the horse(s) and the judgment of pace and horsemanship of the driver. The cross-country marathon can be divided into three or five sections (depending on the level of competition); for each section a maximum and minimum time are allowed (Table 124-1).