Chapter 2 Lameness in Horses

Basic Facts Before Starting

Coexistent Lameness

Horses often have several sites of pain, although one usually is most obvious and the cause of baseline lameness. In many horses, secondary or compensatory (sometimes referred to as complementary) lameness develops in predictable sites or limbs. Concomitant bilateral forelimb or hindlimb lameness is common, but horses often demonstrate more prominent clinical signs in one limb. In horses with palmar foot pain, initially pronounced single forelimb lameness that is abolished by palmar digital analgesia may be present, with subsequent recognition of contralateral forelimb lameness. In racehorses, bilateral lameness, such as in the carpi or metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joints, is common. The clinician should carefully examine the contralateral limb. Predictable compensatory or secondary lameness often exists in the ipsilateral or contralateral forelimb when primary lameness is present in the hindlimb, or vice versa. In a Thoroughbred (TB) racehorse with left forelimb lameness, compensatory problems in the right forelimb and left hindlimb are not uncommon, because these limbs presumably are succumbing to excessive loads while protecting the primary source of pain. In a trotter, diagonal lameness often occurs (primary lameness in the left hindlimb and compensatory lameness in the right forelimb), whereas in pacers, ipsilateral lameness is most common (primary right forelimb and compensatory right hindlimb). When several limbs are involved, identification of the primary or major source of pain is important. If forelimb and hindlimb lameness exist simultaneously, diagnostic analgesic techniques should begin in the hindlimb (see Chapter 10). A common secondary lameness abnormality, proximal suspensory desmitis, can develop in the compensating forelimb or hindlimb.

Coexistent lameness can make assigning primary or baseline lameness to a particular limb during lameness examination difficult (see Chapter 7). Bilaterally symmetrical pain may cause a short, choppy gait, but primary or baseline lameness often cannot be seen when the horse is examined in a straight line in hand. Often, horses with coexistent lameness must be circled, lunged, or ridden for primary or baseline lameness to be observed. The lameness diagnostician may have to arbitrarily assign lameness to a limb and begin diagnostic analgesia in this manner. Often, once the primary source of pain has been identified, horses show pronounced lameness of much greater magnitude than expected in another limb, vivid clinical evidence that coexistent lameness exists.

Lameness Distribution

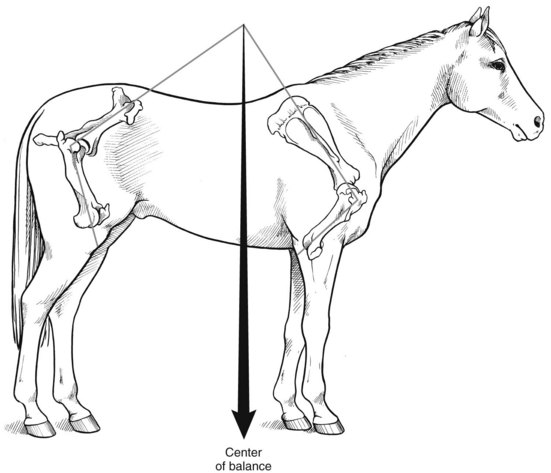

Among all types of horses, forelimb lameness is more common than hindlimb lameness. A horse’s center of gravity or balance, while dictated to a certain extent by conformation (see Chapter 4), is not located in the center of the horse but is closer to the forelimbs than the hindlimbs. Thus the forelimb/hindlimb (F/H) weight (load) distribution ratio is approximately 60% : 40% (Figure 2-1). Higher loads are expected on the individual forelimbs (30% each), predisposing the horse to greater injury.

At certain times during the stride cycle of gaits such as the canter (three-beat gait) and gallop (four-beat gait), a single forelimb is weight bearing, which predisposes the limb to injury. The weight of a rider may shift F/H load distribution to 70% : 30% (Figure 2-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree