Chapter 125Lameness in Draft Horses

Ten Most Common Lameness Problems

| 1. Foot lameness (abscess, hoof cracks, laminitis, and sidebone) | 260 |

| 2. Tarsal lameness (osteoarthritis, bog spavin, and osteochondrosis) | 207 |

| 3. Splints | 84 |

| 4. Tendonitis and suspensory desmitis | 45 |

| 5. Osteoarthritis of the distal interphalangeal or proximal interphalangeal joints | 44 |

| 6. Fetlock lameness (sesamoiditis, osteoarthritis, and osteochondrosis) | 23 |

| 7. Thoroughpin | 18 |

| 8. Carpal lameness (traumatic or infectious carpitis) | 13 |

| 9. Stifle lameness (traumatic, upper fixation of the patella; osteochondrosis) | 10 |

| 10. Myopathy | 8 |

Lameness Common to the Forelimb and Hindlimb

Foot

Subsolar Abscess

Once the abscess is located, the sole should be pared with caution, especially if the horse has a dropped sole or has a concomitant full-thickness hoof wall crack. Overzealous sole paring may result in extensive mechanical damage to laminae and loss of hoof wall strength. Adequate drainage is paramount, but removing a large amount of sole is not necessary, even when substantial undermining has occurred. In draft horses, it is important to err toward a conservative approach, at least initially. Thorough flushing of the foot with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine diacetate solution should be done at least once a day for 3 days or until the drainage has stopped. The foot can be soaked in a saturated solution of magnesium sulfate for 3 to 5 days to reduce inflammation and to aid in drainage. Finding a soak boot large enough for draft horse feet at a reasonable cost is difficult, and I have found an easy solution by using a 1 m length of truck tire inner tubing. The tubing is slipped half its length over the foot, and then up the leg, with the remaining half doubled back up the leg and secured in place by a wrap of choice (Figure 125-1). The tube then can be filled with the soak solution. Draft horses with an uncomplicated subsolar abscess do not need to be treated with systemic antibiotics. However, if cellulitis of the coronary band and pastern region is present, the administration of antibiotics is indicated. Trimethoprim-sulfadiazine (15 mg/kg orally [PO] bid) or ceftiofur sodium (1 mg/kg intravenously [IV] bid or intramuscularly [IM]) is my usual choice. Judicious use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is indicated, but these drugs should not be used for extended periods of time or at levels that may mask a more serious problem. Phenylbutazone, 4 g PO or 2 g IV, on the first day is sufficient. Thereafter, 3 g and then 1 g are given orally on the second and third days, respectively. A tetanus booster should be administered if the horse’s vaccination status is not current or is unknown.

Laminitis

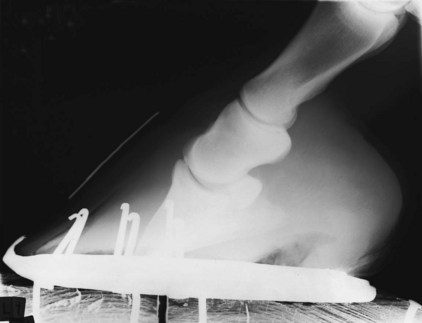

Classification of laminitis is confusing, and I make little attempt to classify laminitis based on chronicity or by using the Obel grading system (see Chapter 34). Regardless of classification used, prognosis for return to function is poor if lameness is severe and persists for longer than 10 days with intensive treatment. In my experience, two major differences exist between draft horses and light horses. First, draft horses develop laminitis more frequently and severely in the hindlimbs. Second, draft horses are more likely to develop distal displacement (sinking) of the distal phalanx once laminitis occurs (Figure 125-2). This latter difference may be related to hoof quality or hoof care in general and the important role that body weight plays in causing distal displacement. In addition, shoeing methods that flair the hoof wall simply to give the impression of a large foot weaken laminar support. Distal displacement can occur in horses with traumatic laminitis without a traditional laminitic episode. Traumatic laminitis and sinking can occur unilaterally, only to then occur weeks to months later in the opposite foot. Traumatic laminitis caused by incorrect shoeing can be reduced greatly or eliminated when proper shoeing is provided on a regular basis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

-inch) round burr on an electric drill and undermining the hoof wall at about a 45-degree angle, leaving a shelf of hoof wall down to the white line on each side of the defect for the full length of the crack. This provides additional surface area for a stronger repair and reduces the likelihood that the repair material will come out. Care must be exercised to avoid damage to the sensitive laminae or to create bleeding during this procedure because these may predispose to abscess formation beneath the repair material. If the horse is initially unshod, a shoe with clips may be sufficient to provide support and to immobilize the defect. Radiator hose clamps and 1-cm long, No. 8 metal screws can be used to stabilize the crack. Because infection is often a problem, the radiator clamp method can be used initially, when filling the defect with repair material is contraindicated. Antibiotic-impregnated repair material has been used, but my success with this material in draft horses has been limited, and my preferred method is a shoe and the radiator clamp and screw combination. It is important to have at least two screws through each piece of clamp and on each side of the defect to add stability. The top clamp should be placed at the proximal limit of the crack. I generally space the clamps 1.9 cm (

-inch) round burr on an electric drill and undermining the hoof wall at about a 45-degree angle, leaving a shelf of hoof wall down to the white line on each side of the defect for the full length of the crack. This provides additional surface area for a stronger repair and reduces the likelihood that the repair material will come out. Care must be exercised to avoid damage to the sensitive laminae or to create bleeding during this procedure because these may predispose to abscess formation beneath the repair material. If the horse is initially unshod, a shoe with clips may be sufficient to provide support and to immobilize the defect. Radiator hose clamps and 1-cm long, No. 8 metal screws can be used to stabilize the crack. Because infection is often a problem, the radiator clamp method can be used initially, when filling the defect with repair material is contraindicated. Antibiotic-impregnated repair material has been used, but my success with this material in draft horses has been limited, and my preferred method is a shoe and the radiator clamp and screw combination. It is important to have at least two screws through each piece of clamp and on each side of the defect to add stability. The top clamp should be placed at the proximal limit of the crack. I generally space the clamps 1.9 cm ( inch) apart, and the number of clamps needed depends on the length, depth, and amount of instability in the crack and on the size of radiator clamp used. The clamps are removed as the defect grows and are replaced if broken. The clamps must be tightened carefully, because lameness from laminar pain will be worse if the clamps are too tight. This problem is corrected by adjusting the clamp with a screwdriver.

inch) apart, and the number of clamps needed depends on the length, depth, and amount of instability in the crack and on the size of radiator clamp used. The clamps are removed as the defect grows and are replaced if broken. The clamps must be tightened carefully, because lameness from laminar pain will be worse if the clamps are too tight. This problem is corrected by adjusting the clamp with a screwdriver.