Chapter 127Lameness in Breeding Stallions and Broodmares

The Stallion

Specific Diagnostic Considerations and Therapy

Neurological Disease

Neurological disease (see also Chapter 11) is usually evident during mounting, intromission, and thrusting, with a stallion stepping on its hind feet, bearing weight on a toe rather than the sole, and sometimes knuckling over. The stallion may bear weight unevenly during thrusting, sometimes becoming high sided on the mare or dummy mount, or falling. The stallion may have reduced proprioceptive control of the penis in seeking and intromission and may have poor anal tone during thrusting. The horse may require extraordinary effort to ejaculate.

Treatment of cervical vertebral malformation (CVM) in adult horses is challenging, and management methods are important, including good footing, proper shoeing, proper positioning of the mare or dummy mount, ground collection of semen, and pharmacological aids to ejaculation when necessary (Box 127-1).1,10 Special precautions must be taken during collection of semen or breeding to protect the stallion, the mare, and the personnel working around the stallion. The mare or dummy mount should be positioned to minimize the risk of a stallion with poor lateral stability falling. Lateral support can be provided at the hips. For semen collection, a mare that does not wiggle from side to side should be used. A dummy mount may be better but usually elicits less vigorous thrusting than a live mount and cannot be moved forward to assist the stallion with dismounting. Surgery occasionally is performed, with recovery taking many months.11

BOX 127-1 Management and Pharmacological Aids to Enhance Libido and Facilitate Ejaculation

Management Aids

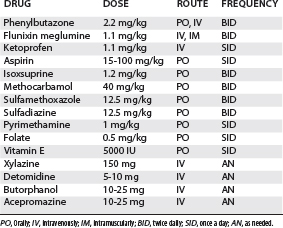

The management of horses with EPM (see Chapter 11) is similar to that for horses with CVM, together with daily pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine or sulfamethoxazole for at least 60 to 90 days (Table 127-1). To prevent anemia, supplementation with folate and vitamin E is advised.12 This treatment does not affect sperm production adversely.13