17 Injuries and diseases of the hoof

The hoof and its components can be regarded as special appendages of the skin. Various conditions caused by environment, injury, neglect or poor farriery practices may cause changes to the wall, sole, frog and/or coronary tissues. These changes may also be related to physical, infectious, neoplastic or genetic factors. It is difficult to categorize the various conditions as they often coexist and many have a common aetiology. For example, a sole crack may lead to an abscess with an under-run sole or wall and then break out at the coronet, thereby involving at least three different hoof structures in different ways.

Genetic defects of the hoof

Thin walls and soles

Treatment

Whilst resting the horses in rocky, rough hill country may produce a harder foot, it seldom corrects the original defect – indeed it may sometimes cause serious break-back of the wall. Thin-soled horses benefit from polypropylene pads or a thin 2–3 mm layer of acrylic filler applied over the whole solar surface. Chrome-treated leather has also been glued with contact adhesive to the soles under the shoes. Glue-on plastic shoes help considerably by avoiding the need for any nails at all but they are not as durable and the methacrylate adhesive often loses its strength if allowed to get wet for long periods. Acrylic hoof support bandages applied around the wall before shoeing assist some horses and can be used to provide extra hoof strength. Daily supplementation with biotin and methionine may improve the quality of the hoof structure but it is not usually curative on its own.

Coronary band (dysplasia) dystrophy

Profile

Key points: Coronary band (dysplasia) dystrophy

Key points: Coronary band (dysplasia) dystrophy

1. A sporadic rare disorder of the coronary band largely restricted to heavy draught breeds. Possibly therefore some genetic aspect.

2. Proliferative, scaling condition of the coronary band only; the pastern skin is usually unaffected. Possibly some consequent alterations in the hoof quality, particularly with loss of periople and a rough, crumbly hoof wall quality.

3. Diagnosis is made by eliminating other causes of coronary band disease and inflammation.

4. Treatment is difficult. Restoration of normal keratinocyte function may be possible with retinoids.

5. The prognosis for resolution is poor – ongoing management and hoof difficulties are almost inevitable. Some horses cope well for many years.

Clinical signs

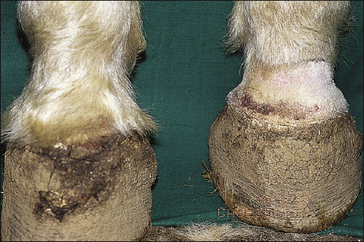

Onset is usually insidious and often the first sign of a problem is the poor hoof wall quality. All four coronary bands show progressive proliferation and hyperkeratotic changes with extensive scaling and have a greasy feel. There are usually obvious hoof wall changes in severe or prolonged cases (Fig. 17.1).

There is no pain or pruritus unless secondary infection develops.

Open lesions are often present with cracks and fissures which can bleed or ooze serum (Fig. 17.2). The ergot and chestnut are seldom affected similarly.

Wall/toe/quarter/heel/vertical or transverse hoof wall cracks

Profile

These are characterized by fissures in the hoof capsule. Coronary band injuries are a common cause of clinically significant secondary cracks and horn defects. Wall, toe and quarter cracks have a defect which is parallel to the laminae, while transverse cracks are at right angles to the laminae. Most cracks of the former type are superficial and due to prolonged desiccation or to trauma/defects of the coronary band. Deep cracks may extend into the sensitive laminae (Fig. 17.3).

Figure 17.3 Deep toe crack extending from solar margin to coronary band and down to sensitive tissue.

Toe and quarter cracks

These are mostly due to neglect from allowing the hoof to dry out, or improper dressing to reduce ‘winging’ of the quarters and heels. They may also arise from sudden turns on rough ground or injuries to the coronary band (Fig. 17.4).

Transverse cracks

Coronary band injuries or infections spreading up the white line from sole abscesses are usually responsible for these. They only become serious if they are extensive and when they have nearly grown out at the solar margin (Fig. 17.5).

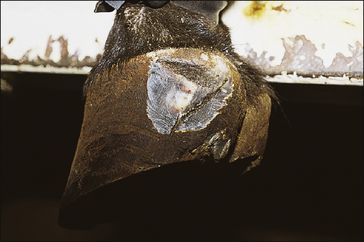

An interesting condition occurs where there is repeated localized bulla formation usually at the dorsal aspect of the coronary band. The condition is pain-free and unexplained. It results in a localized hoof wall deficit that grows down some way before another focus develops. The syndrome is not usually recognized except by farriers (Fig. 17.6).

Sole cracks

These are caused by a combination of excessive drying of the sole and standing on rocks or other hard objects in paddock/grazing horses (Fig. 17.7). They are not commonly observed in shod horses.

Heel cracks

Cracks in the wall of the heel usually have two fairly distinct causes: (a) coronet injury leading to a persistent defect in the coronary band and so to a wall deficit; (b) bearing-surface injuries which seem to occur more frequently from poor heel support. This is encountered where the angle of the heel becomes more and more acute, leading to tearing of the laminae (Fig. 17.8).

Diagnostic confirmation

• Clinical appearance is typical. The extent of crack and/or depth may be determined with a hoof tester applied before and after work.

• Diagnosis of sole cracks is sometimes more demanding. Discoloured horn and the actual line of the crack may only be visible after careful paring of the entire sole surface.

• Long-standing dorsopalmar or mediolateral imbalances which lead to heel cracks are usually easily appreciated.

Treatment

Wall, quarter or heel cracks

Treatment of cracks which involve sensitive laminae often requires regional anaesthesia. The wall of the fissure should be gently debrided using an electric burr (Dremel) and very sharp, fine hoof knives. Tight wire sutures can be placed through the hoof wall to limit movement and the whole area can then be filled with synthetic resin hoof-filling compounds.

Coronary band injuries (wire and overreach wounds)

Profile

Wire cuts or overreaching injuries are very common and are probably the commonest traumatic injury to the hoof and coronary band (Fig. 17.9). Horses paw at fences, hook the heel over wire, and either pull back or saw the leg sideways, often causing extensive damage to the skin, lateral cartilage, tendons and coronary band (Fig. 17.10).

Figure 17.10 Extensive wire injuries involving the hoof, coronary band and deeper tissues of the foot and the pastern and fetlock.

All injuries that physically damage or disrupt the continuity of the corium result in persistent hoof growth abnormalities (Fig. 17.11). In many cases the horse will manage provided that appropriate foot care is given. Complications involving synovial structures, tendons or neurovascular tissues carry a much worse prognosis and in all cases of acute trauma these aspects must be investigated fully.

Clinical signs

Secondary defects in horn growth are very variable and depend largely on the extent of treatment applied at the acute stage. Cracks in the hoof wall commencing at the coronary band defect and extending distally are common outcomes.

Treatment

Very careful assessment of the wound is essential: most are heavily contaminated and/or infected. Prompt, careful debridement using a scalpel (not scissors) of all dead or compromised or contaminated tissues is an essential first step. Hydrosurgical debridement is a useful technique for these injuries because it debrides very efficiently without removing any attached/viable tissue (Knottenbelt 2007).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree