Chapter 31 INFERTILITY

The diagnostic approach and therapeutic management of the infertile dog are perhaps the most difficult and least rewarding areas involving canine male reproduction. Unfortunately, the saying “an azoospermic dog remains azoospermic” is usually true. Nevertheless, a few disorders, if corrected, carry a good prognosis regarding return of fertility. A thorough, systematic diagnostic approach to the infertile dog offers the best chance of discovering the problem. Semen evaluation plays an integral role in the diagnostic evaluation of the infertile dog. It is important to remember that the characteristics of an ejaculate may vary from day to day; an abnormality should be consistently present in the semen before a definitive diagnosis is established. Therapy should be initiated only after a definitive diagnosis has been established. A definitive diagnosis enables the clinician to formulate a rational therapeutic plan and prognosis. The indiscriminate use of fertility drugs, androgens, and hormones is usually ineffective, potentially dangerous, and frequently confusing to both owner and veterinarian.

CLASSIFICATION

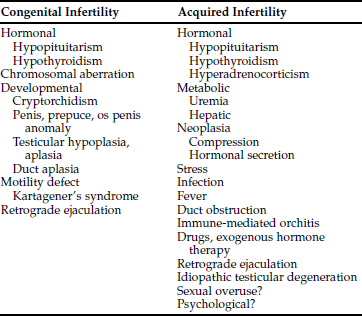

Developing a classification scheme for infertility based on information obtained from the history is a helpful aid in narrowing the list of differential diagnoses and providing insight into the initial diagnostic approach. Classifying infertility based on the dog’s previous breeding history and current status of libido is easily done. Dogs have either acquired or congenital infertility and normal or decreased libido. The most common history we encounter is that of a proven stud dog with acquired infertility. Libido is typically normal but then wanes. Acquired infertility has many possible causes (Table 31-1). A dog that has never sired a litter despite numerous attempts should be considered congenitally infertile until proved otherwise. Acquired infertility is possible in these dogs if the insult occurred before the onset of sexual use. In addition to acquired causes, the clinician must also consider congenital defects that would not be considered in the previously proven stud dog (Table 31-1).

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Initial Evaluation

HISTORY.

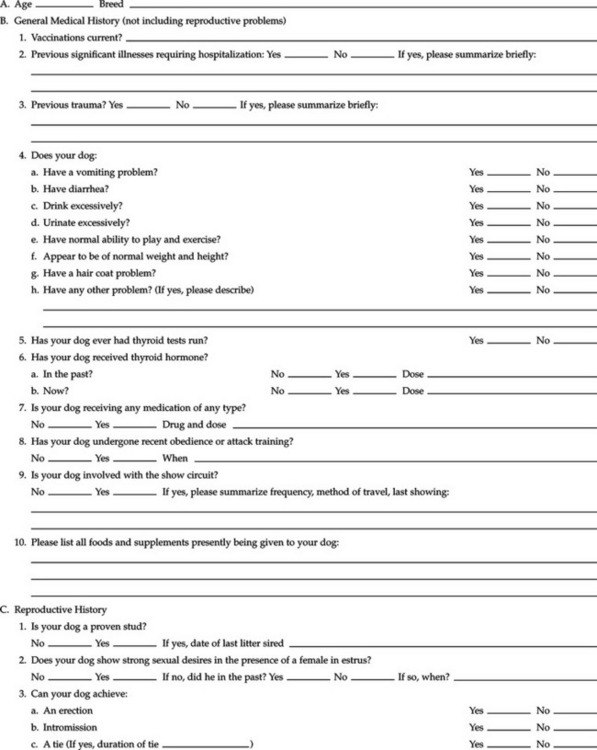

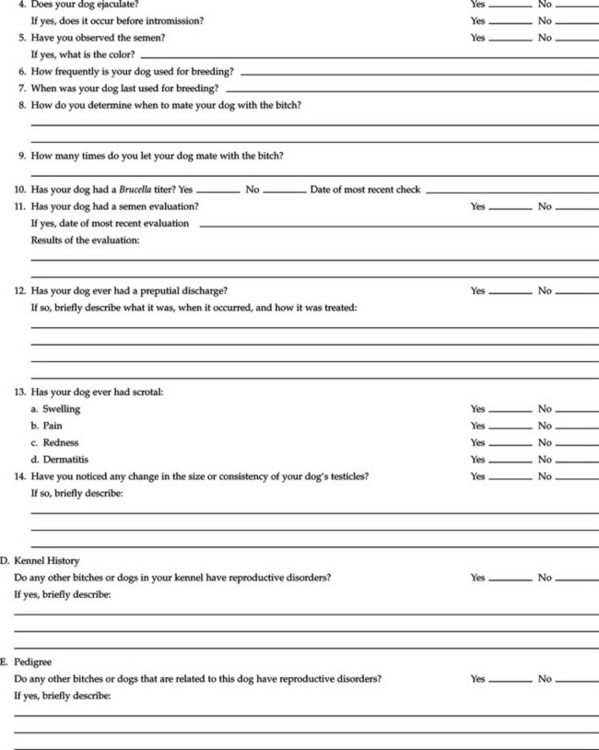

The differential diagnoses and diagnostic approach to potentially infertile dogs should be based on information obtained from the history and physical examination. A thorough history is extremely important in the evaluation of the infertile dog. The history should establish the previous fertility of the dog and the current status of libido. In addition, a complete reproductive history should be ascertained, as well as a knowledge of factors such as the dog’s environment, use, previous illnesses, medications, and trauma (Table 31-2). Attention should be paid to the age of the animal, frequency of sexual use, breeding practices of the kennel, presence or absence of previous reproductive problems, and previous or current use of any hormones or other medications. Several drugs and exogenous hormones have been associated with infertility in the dog (Table 31-3). As a general rule, any drug therapy can potentially result in infertility. Genetic factors may also contribute to infertility and should be suspected if inbreeding, infertility in related dogs, or problems with other endocrine disorders (e.g., lymphocytic thyroiditis) are identified (Olson et al, 1992). Finally, a thorough review of breeding management practices and the fertility of bitches with which the dog has bred should be done. In many instances, the problem lies with inappropriate timing of the breedings, technical mistakes if artificial insemination was used, or fertility problems with the bitch rather than the dog.

TABLE 31-2 OWNER QUESTIONNAIRE–THE INFERTILE MALE

TABLE 31-3 DRUGS AND EXOGENOUS HORMONES THAT AFFECT FERTILITY IN HUMANS AND POSSIBLY THE DOG

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION.

A complete physical examination is extremely important in the evaluation of the infertile dog. Abnormalities involving other organ systems besides the reproductive tract can interfere with spermatogenesis or libido. A thorough examination of the reproductive tract (see page 930) should be performed once all other organ systems have been examined. In the infertile dog, special attention should be given to the size, shape, and location of the os penis in relation to the tip of the glans penis; the preputial opening and the ability to extrude the penis; the size, shape, and consistency of the testes; the size and conformation of the epididymis and spermatic cord; and the size, symmetry, and consistency of the prostate gland. Any identified abnormalities should be evaluated as needed.

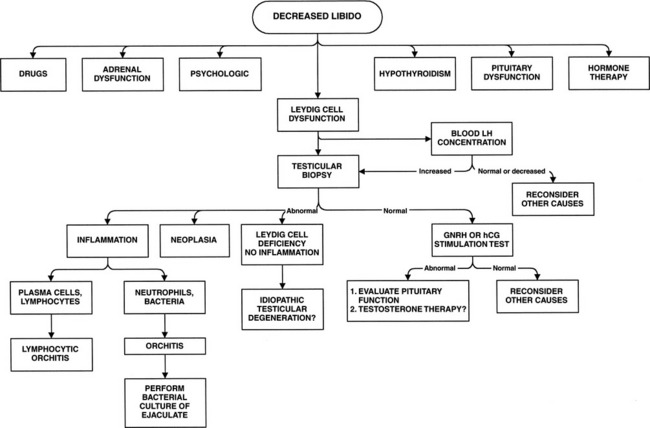

Infertility and Decreased Libido

Decreased libido varies from complete lack of sexual interest and inability to mate, to slowness or delay in exhibiting libido or attaining an erection, to an increasing inability or disinterest in mounting the bitch and achieving intromission (Keenan, 1998). Decreased libido implies a reduction in the circulating concentration of testosterone or an acquired psychogenic problem resulting in loss of interest in mating (Fig. 31-1). Severe discipline for inappropriate mounting, exposure to aggressive or dominant bitches at the time of breeding, removal of the dog from his surroundings, or erratic behavior from the owner may deleteriously affect libido, especially if the negative influences occur early in life. Breeding at the incorrect time of estrus, sexual overuse, and painful orthopedic conditions can affect the performance of the dog. Some dogs also have pronounced mate preferences, resulting in inconsistent libido. Rarely, diminished olfactory function may inhibit libido by altering the dog’s perception of pheromones (Freshman, 2001).

An ejaculate may be difficult to obtain in a dog with decreased libido, although obtaining a semen sample should be attempted. If an ejaculate can be obtained, a thorough evaluation and microbiologic culture should be performed (see pages 932 and 941). Results of these tests may provide clues to the underlying problem. If the semen evaluation and culture are inconclusive or an ejaculate cannot be obtained, cytologic evaluation of a testicular aspirate or histologic evaluation of a testicular biopsy should be considered to evaluate the condition of the seminiferous tubules and the Leydig cells (see pages 947 and 949). Secondary causes of decreased libido should be ruled out before performing a testicular biopsy. Blood luteinizing hormone (LH) concentrations are increased with loss of Leydig cells. Therefore assaying the blood LH concentration can be used to increase suspicion for a primary testicular problem (see page 945).

Acquired Infertility and Normal Libido

This is the most common cause for infertility in dogs. Normal libido suggests that the pituitary–Leydig cell axis is functional and that blood testosterone concentrations are adequate. Because of the large number of differential diagnoses (Table 31-4), an evaluation should be designed to progress from relatively easy and inexpensive to more difficult and time-consuming diagnostic tests. Three critical areas should be pursued in the history: (1) a thorough review of breeding practices, focusing especially on the method by which the owner determines when a bitch is to be bred, the number of times the bitch is bred during estrus, the establishment of a tie, the fertility status of the bitch(es), the frequency of use of the dog, and the sexual experience of the dog; (2) a thorough review of medications currently or previously given to the dog; and (3) a thorough review of current and past illnesses, trauma, and stresses. Stress can inhibit reproductive function (Rivier and Rivest, 1991), and although the term stress is difficult to define, anything from serious illness to activity out of the expected ordinary routine for a dog should be considered. For example, frequent flying or participation in stressful activities (e.g., Schintzund training) can cause temporary infertility. Potential inciting factors identified in the history should be corrected, if possible.

TABLE 31-4 POTENTIAL CAUSES FOR ACQUIRED INFERTILITY AND NORMAL LIBIDO

| Common Causes | Uncommon Causes | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal dog | Sexual overuse | |

| Breeding mismanagement | Testicular trauma | |

| Problems with artificial insemination technique | Testicular hyperthermia | |

| Testicular neoplasia | ||

| Drugs, environmental insults | Retrograde ejaculation | |

| Scrotal inflammation | Bilateral duct obstruction | |

| Systemic illness (current or previous) | Chronic severe stress | |

| Kartagener’s syndrome | ||

| Infectious orchitis | Brucella canis | |

| Lymphocytic orchitis | Hemospermia | |

| Idiopathic testicular degeneration | Asthenozoospermia | |

| Old age | ||

Regardless of the historical findings, a thorough physical examination, Brucella canis test, and semen evaluation should be performed to rule out other possible problems. During the physical examination, the clinician should make special note of testicular size, symmetry, and consistency. The type of testicular abnormalities identified on palpation may provide clues to the underlying cause (see Physical Examination, page 930). Rectal palpation of the prostate should be performed to evaluate for changes consistent with chronic prostatitis. All dogs with an infertility problem should be evaluated for B. canis, using the rapid slide or tube agglutination test (see page 920).

A semen evaluation is critical in the diagnostic evaluation of the dog with acquired infertility and normal libido. (see page 932 for a complete discussion on obtaining and evaluating an ejaculate.) Abnormalities identified on evaluation of semen can provide clues to the underlying cause and dictate the next steps in the diagnostic evaluation of the dog. The diagnostic approach to some of the more common abnormalities identified on semen evaluation follows. The reader is referred to Chapter 27 for detailed information on the diagnostic tests discussed below.

Azoospermia (Fig. 31-2)

Azoospermia refers to a complete absence of spermatozoa in the ejaculate. Azoospermia is typically associated with normal seminal fluid. Identification of normal concentrations of seminal alkaline phosphatase confirms the presence of epididymal fluid in the ejaculate (see page 940). Identifiable abnormalities in seminal fluid can provide valuable insight into the possible underlying cause and should always be pursued (see below). In our experience, azoospermia is usually an acquired disorder that develops secondary to gonadal dysfunction, most notably idiopathic testicular degeneration (Table 31-5).

TABLE 31-5 POTENTIAL CAUSES FOR AZOOSPERMIA

| Azoospermia May Be Transient | Azoospermia Usually Permanent |

|---|---|

| Drugs, hormones* (see Table 31-3) | Idiopathic testicular degeneration |

| Environmental insult | Lymphocytic orchitis |

| Systemic illness (current or previous) | Brucella canis |

| Duct obstruction | |

| Testicular trauma, hyperthermia | Bilateral testicular neoplasia |

| Infectious orchitis, prostatitis | Congenital defect |

| Retrograde ejaculation | |

| Hypothyroidism* | |

| Hypopituitarism* | |

| Hyperadrenocorticism* | |

| Estrogen-secreting Sertoli cell tumor* |

* Decreased libido often associated with these disorders.

Azoospermia should always be confirmed with several ejaculates before embarking on an extensive evaluation for causes—and certainly before declaring a dog sterile. Incomplete ejaculation can result in “apparent” oligospermia and occasionally azoospermia, especially in a young, timid male who is outside of his normal domain or in a dog experiencing pain during the collection procedure (e.g., failure to exteriorize the bulbus glandis). Evaluating several ejaculates and paying attention to careful and correct collection techniques usually allow identification of incomplete ejaculation.

Potential causes of azoospermia include drugs; environmental insults (e.g., exposure to heavy metals, mercurial compounds, and other toxins); systemic disease; bilateral obstruction of the vas deferens, epididymides, or ductulus deferens; retrograde ejaculation; gonadal dysfunction; and genetics (Olson, 1991). A thorough history concerning past and current drug therapy should always be obtained and reviewed (see Table 31-3). Information regarding the environment and potential for exposure to household and environmental chemicals and toxins should be pursued. Genetic factors may contribute to azoospermia and should be suspected if inbreeding, infertility in related dogs, or problems with endocrine disorders (e.g., lymphocytic thyroiditis) are identified (Olson et al, 1992). The following tests should be performed to screen for systemic disease that may be deleteriously affecting spermatogenesis: a complete blood count (CBC); serum biochemistry panel; thyroid panel, including total thyroxine, free thyroxine by modified equilibrium dialysis, and endogenous thyrotropin concentration; and urinalysis.

Obstruction of the duct system can result from inflammation, neoplasia, segmental aplasia, sperm granuloma, spermatocele, or prior vasectomy (Olson, 1991). A thorough palpation of the testes and epididymides may reveal pain, swelling, or mass lesions. An ultrasound examination of the testes, epididymides, vas deferens, and prostate gland may also reveal abnormalities in these structures. Patency of the duct system can be determined by measuring seminal alkaline phosphatase concentration (see page 940).

Retrograde ejaculation refers to the passage of semen into the urinary bladder during ejaculation. During normal antegrade ejaculation, sequential seminal emission, bladder neck closure and seminal expulsion through the penile urethra occur; these events are controlled primarily by the sympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system (Root et al, 1994). Denervation or damage to the nerves or muscles in this system prevent this sequence of events. If there is inadequate closure of the bladder neck, semen will flow into the urinary bladder, because this is the path of least resistance (Frenette et al, 1986). Retrograde flow of some semen occurs during normal ejaculation in the dog (Dooley et al, 1990). Complete retrograde ejaculation is rare but should be considered a potential problem in the azoospermic dog. Partial retrograde ejaculation causing oligospermia can also occur. Documenting large numbers of spermatozoa in a urinalysis obtained after ejaculation versus one obtained before ejaculation establishes the diagnosis.

Congenital defects in testicular development and spermatogenesis should be considered in the young adult dog or in the dog that has never sired a litter despite multiple attempts. Intersex states (e.g., XXY syndrome) are the most common congenital causes for azoospermia (Nie et al, 1998). A thorough physical examination often reveals abnormalities (e.g., testicular hypoplasia) suggestive of a gonadal problem. Karyotyping should be done if intersexuality is suspected. Refer to Chapter 24 for information on intersexuality.

Acquired gonadal disorders that cause azoospermia in the dog with normal libido include idiopathic testicular degeneration, lymphocytic orchitis, infection, thermal insult, trauma, and neoplasia. Endocrine disorders, most sex hormones, and glucocorticoids typically affect libido as well as spermatogenesis; androgens are the exception (see page 1003). Most of these disorders typically cause oligospermia initially. With time, disorders causing acquired loss of spermatogenesis, most notably idiopathic testicular degeneration, may also decrease the dog’s libido, as the Leydig cells also become affected. Acquired disorders often result in abnormalities identifiable on physical examination. Abnormalities (e.g., inflammatory cells, bacteria) in the seminal fluid may also be identified. Normal seminal fluid is common with idiopathic testicular degeneration and may also be found as an end-stage event with other disorders.

Dogs with suspected acquired gonadal dysfunction should have bacterial infection ruled out through cultures of the urine, semen, and, if identifiable with ultrasonography, prostatic cyst(s). An ultrasound examination of the testes and epididymides by an experienced ultrasonographer should be performed and any identifiable masses or cysts aspirated for cytology and culture. Cultures must be interpreted cautiously. Bacteria that are isolated may represent a primary infection causing infertility, may be secondary invaders and not the primary problem, or may be contaminants. In addition, bacteria isolated in semen may be different from those isolated from testicular tissue or prostatic cysts (Olson et al, 1992). Nevertheless, antibiotic therapy may be warranted in an azoospermic dog when bacterial cultures are positive.

If available, measurement of serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) concentration can provide information on the health of the seminiferous tubules. The baseline serum FSH concentration is typically less than 130 ng/ml in healthy dogs. Infertile dogs with severe testicular dysfunction typically have serum FSH concentrations greater than 250 ng/ml (Soderberg, 1986). Increased concentration of FSH likely results from decreased production of inhibin by Sertoli cells in response to abnormal spermatogenesis and subsequent loss of feedback inhibition on pituitary FSH secretion. Conversely, normal or low serum FSH concentration in an azoospermic dog suggests bilateral tubal obstruction within the duct system, retrograde ejaculation, impaired pituitary FSH secretion (i.e., hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism), or sampling error (see page 945).

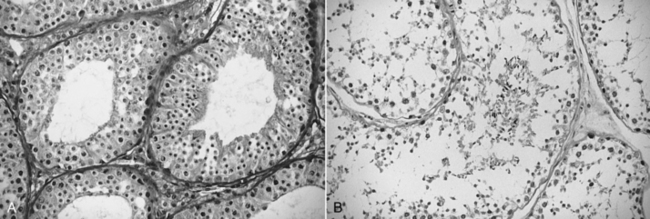

Testicular biopsy provides concrete information on the underlying pathologic process (e.g., lymphocytic orchitis, seminiferous tubule degeneration), the state of the blood-testis barrier, the cellularity of the seminiferous tubules, and the potential for regeneration of spermatogenesis and may provide guidance regarding therapy (Olson et al, 1992). Aspirated testicular tissue can also be submitted for culture. When evaluating a testicular biopsy, it is important to remember that biopsied tissue represents a focal area of the testis and may not be representative of the disease process affecting the testis. In addition, it is often difficult to determine whether the seminiferous tubules are undergoing degeneration or regeneration based on a testicular biopsy obtained at one point in time, especially if inflammation is not present (Fig. 31-3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree