Chapter 22 INDUCED ABORTION, PREGNANCY PREVENTION AND TERMINATION, AND MISMATING

THE PROBLEM: UNWANTED PREGNANCY

Contraceptive medications are available that prevent a bitch from cycling by delaying the onset of proestrus. These drugs are approved for use in the bitch and are successful. However, such agents have limitations that prevent their widespread use in bitches. They are not to be used prior to the first estrus; they cannot or should not be used for prolonged periods; they may change behavior or activity levels; and they are not recommended for use in brood bitches (Von Berky and Townsend, 1993).

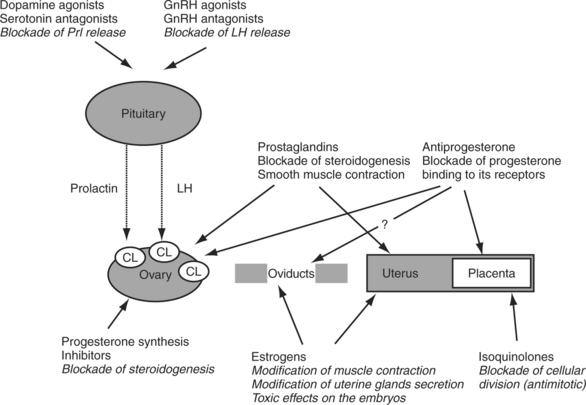

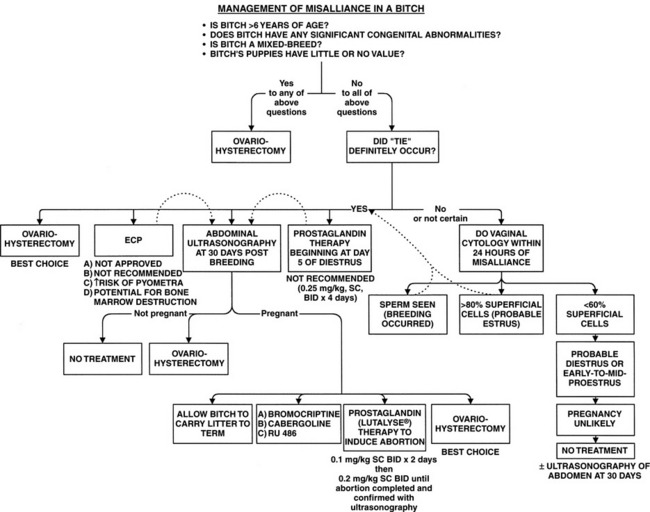

INITIAL EVALUATION (Fig. 22-1)

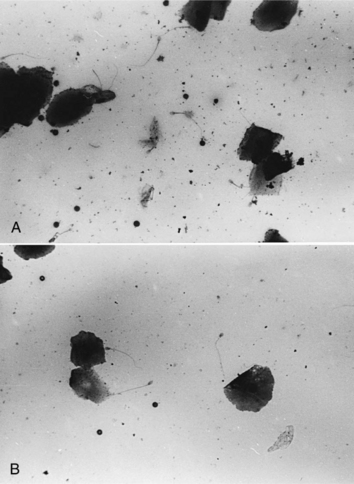

A vaginal smear is the best diagnostic tool for evaluating mismated dogs. A large majority of bitches have sperm or sperm heads in the vaginal smears for 24 to 36 hours after breeding (Fig. 22-2). Forty-eight hours after breeding, 50% of bitches still have sperm or sperm heads on vaginal cytology (Olson, 1989). The presence of sperm or sperm heads confirms that breeding took place. However, lack of sperm does not prove that a fertile breeding did not occur.

The vaginal smear may also indicate the stage of the cycle. Bitches in diestrus, anestrus, or early to middle proestrus (majority of vaginal cells are parabasal and/or intermediate type) are unlikely to be fertile, and the owners need not be concerned about an unwanted pregnancy. However, if the bitch is in estrus, she must be assumed to be fertile and may have bred. Greater than 80% superficial cells on vaginal cytology is strong evidence of estrus (standing heat) with or without the presence of sperm. However, greater than 80% superficial cells with a concurrent plasma progesterone concentration less than 2 ng/ml would indicate that the bitch is most likely in late proestrus, not willing to breed, and not fertile.

TREATMENT OF BITCHES VALUABLE FOR BREEDING PURPOSES

Pregnancy “Trimesters”

SECOND TRIMESTER.

Pregnancy can be confirmed during this second period and abortion induced if necessary. Abortion induction can be associated with fetal resorption or expulsion (Fig. 22-3). Abortion can be induced with prostaglandins (natural or synthetic), antiprolactin agents (e.g., dopamine agonists, such as bromocriptine and cabergoline), or antiserotoninergic agents (methergoline); with a combination of prostaglandins and dopamine agonists; or with inhibitors of progesterone secretion (epostane) or progesterone action (mifepristone or aglepristone). Inducing abortion in a bitch known to be pregnant has obvious advantages over attempting to cause abortion when pregnancy has not been confirmed (Verstegen, 2000).

THIRD TRIMESTER.

The last trimester is one that begins with calcification of fetal skeletal structures. Fetuses are well developed, and abortion is always associated with fetal expulsion. Due to the wide variation in duration of pregnancy (when calculated from breeding dates, for example), abortion might induce premature parturition with delivery of live pups. For this reason, we recommend initiation of abortion protocols in bitches between days 30 and 35 after the onset of diestrus or from the date of last breeding (see Fig. 22-1).

Ovariohysterectomy

The bitch with potential value through the sale or use of her offspring is not usually a candidate for ovariohysterectomy because owners want to maintain her fertility. The age and reproductive history of such dogs should be considered. The bitch or dog may have conformation deficiencies that reduce the value of their offspring. Realistically, some bitches have little reproductive potential because of age, previous illness, or other factors. Discussion of these issues helps an owner to choose the appropriate therapy (Olson and Johnston, 1993).

Abortion Prior to Implantation: Estrogens (Not Recommended)

PHYSIOLOGY.

Fertilization of eggs and the initial 6 to 10 days of canine embryonic development take place in the oviducts or fallopian tubes (Jackson and Johnston, 1980). Days later, the developing embryos migrate into the uterus and attach to the endometrium via a placenta for continued growth and nourishment. If embryos can be retained in the oviducts during the time they normally migrate and implant, degeneration and death occur. Large doses of estrogen can prolong the time the embryo is restricted to the oviduct, and this is the goal of therapy (Post, 1995).

Estrogens administered at the correct dose and time after an unwanted breeding have two potential mechanisms of action. In one, estrogen tightens the uterotubular junction (the junction connecting the oviducts with the uterus), prolongs oviductal retention of embryos, and prevents migration of the developing embryo into the uterus, thereby ending pregnancy (Soderberg and Olson, 1983). In addition, estrogen may have direct degenerative effects on ova and may also alter the endometrium to prevent implantation (see Fig. 22-3). Several estrogen preparations have traditionally been used to prevent pregnancy in small animal practice.

DIETHYLSTILBESTROL (DES).

Injection of DES (2 mg/kg body weight, up to 25 mg) once or twice within 5 days of mismating appeared to be quite successful in terminating pregnancy. However, injectable DES is no longer available to veterinarians. Oral DES has been recommended at a dosage of 1 to 2 mg/day for 7 days after mismating (Soderberg and Olson, 1983); or 75 μg/kg/day for 7 days (Bowen et al, 1985). However, oral DES has not been found to be a reliable therapy. Eleven of 12 bitches treated with DES during proestrus, estrus, or diestrus became pregnant (Olson et al, 1984; Bowen et al, 1985). Further, DES has been associated with potential side effects, which are discussed later.

ESTRADIOL CYPIONATE (ECP).

Estradiol cypionate (estradiol 17β-cyclopentyl propionate) was an estrogen compound commonly used by veterinarians in the management of mismating (Jackson and Johnston, 1980). Several intramuscular dosage schedules were used and/or recommended. These protocols include one-time doses administered within 3 days of mismating: 0.25 to 1 mg total dose; 0.02 mg/kg, never to exceed 1 mg; and 0.04 mg/kg, never to exceed 1 mg (Burke, 1986). More so than DES, ECP has been associated with serious potential side effects. At 0.02 mg/kg, the drug was successful in preventing pregnancy in only 50% of bitches during proestrus or estrus and in 75% of bitches demonstrated to be in diestrus. The 0.04 mg/kg dose was 100% successful in preventing pregnancy in bitches receiving that dosage during estrus or diestrus (Olson et al, 1984; Bowen et al, 1985).

Despite the potentially favorable information on successful termination of pregnancy, ECP has major side effects that limit or eliminate its usefulness. Pyometra developed in two of eight dogs receiving ECP during diestrus (Bowen et al, 1985). Furthermore, ECP is well recognized as having the potential for causing permanent bone marrow suppression or destruction (or both) in dogs, resulting in severe anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and death. This life-threatening syndrome may be caused even when ECP is given at proper dosages (Olson et al, 1984). Bone marrow suppression has been diagnosed 2 to 8 weeks after administration. For these reasons, the manufacturer has not approved ECP for use in dogs for any purpose, and we do not recommend its use.

ESTRADIOL BENZOATE, ESTRADIOL VALERATE, AND ESTRONE.

Estradiol valerate has a long duration of action, and the recommended dosage is 3.0 to 7.0 mg administered once 4 to 10 days after mismating (Burke, 1986). Estradiol benzoate has a shorter duration of action, and the dosage recommendation is 5 to 10 μg/kg with a maximum of 1 mg per dog. This dose is divided into two or three subcutaneous injections, which are given at 48-hour intervals beginning on day 2 to day 4 after mating (Verstegen, 2000). Another protocol is 0.5 to 3.0 mg given every other day, for a total of three injections, beginning 4 to 10 days after misalliance (Burke, 1986). Estrone is also commercially available. The dose recommended is a single injection of 2.5 to 5.0 mg administered within 5 days of misalliance (Burke, 1986).

ESTROGEN-INDUCED PYOMETRA.

Estrogen preparations (DES and ECP) are thought to increase the incidence of pyometra. Estrogen predisposes bitches to pyometra by sensitizing progesterone receptors and enhancing the binding of progesterone to the endometrium (Niskanen and Thrusfield, 1998). There do appear to be two distinct pyometra syndromes in the dog. One is a uterine infection seen in older bitches that have an acquired uterine condition called cystic endometrial hyperplasia (CEH). Pyometra is a potential sequela to the chronic presence of CEH. The second, more common and more worrisome pyometra syndrome is uterine infection of young bitches secondary to estrogen administration. Pyometra, open or closed cervix, can occur 1 to 10 weeks after mismating therapy.

Our continuing clinical trials provide evidence against long-term damage to the endometrium as a result of exogenous estrogen therapy. However, the exogenous estrogen causes transient uterine disease (pyometra); this condition is not only life threatening, it also is treated by ovariohysterectomy in most hospitals. Bitches with pyometra that are successfully treated with prostaglandins have an excellent prognosis for carrying pregnancies to term in subsequent cycles (Nelson et al, 1982). Thus a chronic endometrial disorder is not present. However, some bitches treated with estrogen do have recurrences of pyometra. Pyometra has been diagnosed in young bitches that never received estrogens at any time. However, pyometra as a naturally occurring disease in the young bitch (less than 6 years of age) is not nearly as common as it is in the estrogen-treated bitch. For these reasons (pyometra and bone marrow destruction), the use of estrogen compounds in the management of misalliance is strongly discouraged.

ESTROGEN-INDUCED BONE MARROW DESTRUCTION.

Excesses in the serum estrogen concentration caused by exogenous estrogen treatment always have the potential to destroy the bone marrow in dogs (Verstegen et al, 1981). This bone marrow sensitivity to estrogen is not well understood. Bone marrow destruction may occur after exposure to abnormal increases in the serum estrogen concentration from endogenous sources (e.g., Sertoli and interstitial cell tumors in males) (Suess et al, 1992), as well as from exogenous sources. The most common and dangerous exogenous source of excess estrogen is administration of ECP.

Lithium carbonate (11 mg/kg PO bid for 6 weeks) has been reported as a possible treatment for estrogen-induced bone marrow hypoplasia (Hall, 1992). Lithium treatment, however, needs to be evaluated in a larger group of dogs to assess efficacy. Side effects of this drug include tremors, hypothyroidism, renal tubular nephropathy, edema, and cardiac “sick sinus” syndrome. Close patient monitoring, therefore, is critically important. Administration of recombinant canine granulocyte colony-stimulating factors may be more effective and safer than lithium therapy.

ESTROGEN-INDUCED BEHAVIOR CHANGES.

The least worrisome side effect of estrogen administration is induction or prolongation of estrus behavior (Jackson and Johnston, 1980). These bitches may continue attracting males for 7 to 10 days. Some have prolonged standing heat, and others reenter standing heat.

Prostaglandins in General

PHYSIOLOGY.

Pregnancy in the bitch depends on progesterone secretion from corpora lutea. Ovariectomy (which would result in immediate loss of all progesterone) or inhibition of progesterone synthesis at any stage of gestation results in fetal resorption or abortion. Administration of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) or its analogs has been repeatedly demonstrated by researchers to successfully terminate pregnancy in the bitch. Abortion with prostaglandins is induced through three different mechanisms: (1) by inducing vasoconstriction, reducing blood flow to the corpora lutea and causing cellular degeneration; (2) by interfering with progesterone synthesis through binding to specific receptors; and (3) by acting directly on the myometrium to cause smooth muscle contractions.* The myometrial contractions are associated with natural prostaglandins, not the synthetic analogs. Most of these studies have been performed on laboratory dogs using a variety of protocols. Several clinical reports have also suggested that PGF2α could be used by veterinary practitioners to terminate pregnancy in the bitch (Lein, 1983; Johnston, 1990; Feldman et al, 1993).

Natural Prostaglandins

RECOMMENDED TREATMENT PROTOCOL.

Abdominal ultrasound is recommended approximately 30 days after the last (or unwanted) breeding or 30 days after the first day of diestrus as confirmed with vaginal cytology. After pregnancy has been confirmed, abortion should be discussed with the owner. In our opinion, the use of prostaglandins at this time of gestation is effective and safe. Treatment prior to day 30 is not recommended. No evidence of straining or dystocia has been observed in any bitch. It is assumed, in part, that difficulty in delivery of fetuses is unlikely because each fetus is so small that it can be passed through the birth canal even if presented in an abnormal posture.

Our current recommendation is the protocol that acted most rapidly while resulting in the fewest and/or least severe side effects: natural PGF2α at a dosage of 0.1 mg/kg given subcutaneously every 8 hours for 2 days, and then 0.2 mg/kg given subcutaneously every 8 hours daily until abortion has been completed, as confirmed by abdominal ultrasonography. This protocol resulted in the least severe side effects and the fewest number of days to complete the abortion process (Feldman et al, 1993).

MONITORING.

Abdominal ultrasound was performed every 48 hours until abortion was completed. We now recommend that abdominal ultrasonography be performed within 6 to 12 hours and prior to the next scheduled administration of PGF2α if abdominal contractions, fetuses, or bloody or dark vaginal discharge are observed. A physical examination, including abdominal palpation, should be performed at least twice daily. After each injection of PGF2α, the dog should be taken for a 20- to 30-minute walk, which allows close observation of the animal. The dog should be fed 1 to 2 hours after prostaglandin injection so as to avoid vomiting with feeding prior to treatment. The feeding period can also be used as an observation period (Feldman et al, 1993).

COMPLETION OF PROSTAGLANDIN ADMINISTRATION.

Several bitches were observed to abort one or more fetuses, only to have the subsequent abdominal ultrasound examination demonstrate live fetuses in utero. These dogs required 1 to 3 additional days of PGF2α administration to complete the abortion process, a fact that demonstrates that monitoring any bitch being treated with prostaglandins without ultrasonography is not reliable. Furthermore, most of the bitches were not seen to abort any of their litters. In other words, many bitches quickly consume stillborn neonates. Most of the fetuses seen were expelled with membranes intact, and none survived longer than a few minutes. Fetal resorption, although possible, appears to be unlikely in bitches managed with prostaglandins because no in utero fetal material has been identified on ultrasonography performed on any of the bitches we have treated (Feldman et al, 1993).

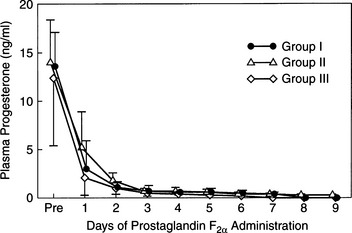

SERUM PROGESTERONE CONCENTRATIONS.

It has been suggested that plasma progesterone concentrations less than 2.0 ng/ml result in pregnancy termination in bitches (Olson et al, 1986). The pretreatment plasma progesterone concentrations were greater than 6.0 ng/ml in all bitches we treated. As shown in Fig. 22-4, the mean plasma progesterone concentration from all the bitches decreased after the start of PGF2αadministration. The plasma progesterone concentration decreased in all dogs approximately 50% from the pretreatment concentration after only 24 hours of PGF2α treatment. After 72 hours and at each subsequent blood sampling time, all treated bitches had plasma progesterone concentrations less than 2.0 ng/ml. No bitch aborted any fetal material until at least 24 hours after the plasma progesterone concentration was less than 2.0 ng/ml (Feldman et al, 1993). Although monitoring of the plasma progesterone concentration is not necessary, these results demonstrate the physiologic effect of prostaglandin administration, as well as the speed with which it acts.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

) was treated with 0.1 mg/kg every 8 hours; group II (

) was treated with 0.1 mg/kg every 8 hours; group II ( ) was treated with 0.25 mg/kg every 12 hours; group III (

) was treated with 0.25 mg/kg every 12 hours; group III ( ) was treated with 0.1 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2 days and 0.2 mg/kg every 8 hours thereafter. Each group was composed of six pregnant bitches. All bitches aborted all fetuses in 9 days or less.

) was treated with 0.1 mg/kg every 8 hours for 2 days and 0.2 mg/kg every 8 hours thereafter. Each group was composed of six pregnant bitches. All bitches aborted all fetuses in 9 days or less.