CHAPTER 49In Vitro Oocyte Maturation

Recovery of immature oocytes from excised ovaries, followed by maturation of these oocytes in vitro, may be done to obtain foals after the death of a valuable mare1 or to conduct research on oocyte physiology and fertilization. Methods for recovery and classification of horse oocytes vary substantially from those for oocytes of other species, and veterinarians working in this area should familiarize themselves with methods specific to the horse.

OOCYTE RECOVERY

The oocyte of the horse is difficult to dislodge from the follicle wall. In cattle follicles the oocyte and its surrounding cumulus cells protrude into the follicle lumen on a narrow “neck,” which is easily broken; however, in the horse the oocyte is imbedded within the granulosa layer that lines the follicle.2 In addition, the equine cumulus is firmly anchored to the ovarian stroma (theca) beneath it by numerous projections. For these reasons, aspiration of follicles with a needle and syringe or vacuum apparatus, as done for bovine oocytes, results in a low yield of oocytes in the horse. In addition, aspiration preferentially recovers oocytes from partially atretic follicles, in which the granulosa is starting to degenerate and is losing integrity.3 Therefore the preferred method for recovery of oocytes from horse ovaries is to slice open the follicles and to scrape the entire granulosa cell layer from the follicle to recover the oocyte.

The contents of each follicle are washed into a separate dish. Once all of the visible follicles on the surface of the ovary have been processed, the ovary is sliced in 0.5-cm slices to visualize any follicles within the ovary. All follicles on the ovary may be processed; although the maturation rate for oocytes from small follicles is lower than that for large follicles, they still have the potential to perform successfully.4

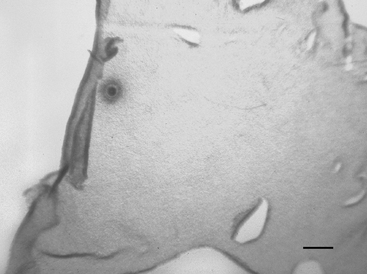

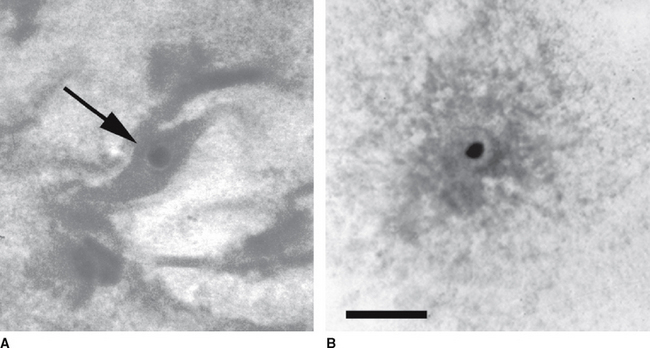

Each Petri dish is examined under a dissection microscope at 10× to 40× to locate the oocyte. The character of the mural granulosa cells within the dish should be evaluated at this time. Compact granulosa appears as sheets of tissue (Figure 49-1). These sheets may have ragged edges where they are torn but when viewed from the side have a smooth surface without evidence of protruding cells. The smoothness of the granulosa is best evaluated by examining the edge of a fold of tissue. Expanded granulosa ranges from sheets of tissue with uneven granularity and cells protruding from the surface (Figure 49-2, A), to shards of slightly puffy tissue, to completely expanded, cloudlike masses of cells (Figure 49-2, B), often with a yellow coloring.

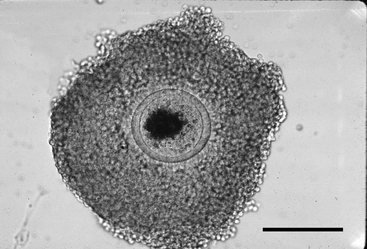

The oocyte may be difficult to locate because it may be imbedded within a sheet of tissue (see Figures 49-1 and 49-2, A) or be in the middle of a large mass of expanded cells (see Figure 49-2, B). As opposed to an embryo, which is completely spherical, the oocyte may appear to be irregular in shape (see Figure 49-2, B). This may be due to asymmetrical distribution of the dark granules within the oocyte cytoplasm (Figure 49-3). In cattle such oocytes are discarded because they do not have a homogenous cytoplasm; however, in horses this asymmetrical distribution of granules actually indicates that the oocyte is meiotically competent.5

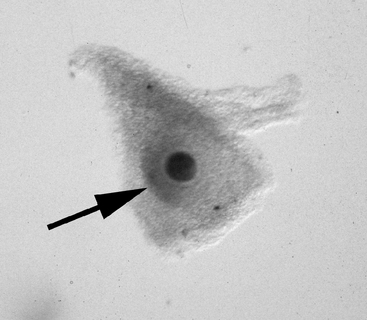

Once the oocyte is located, the character of the cumulus should be evaluated. The cumulus may best be examined by evaluating the smoothness of the surface of the granulosa that forms the hillock over the oocyte (Figure 49-4); it may be necessary to turn the oocyte on its side in order to evaluate this. In this author’s laboratory, only oocytes that have a compact cumulus and compact mural granulosa are classified as compact (Cp); oocytes having either expansion of the cumulus or expansion of the mural granulosa, or both, are classified as expanded (Ex). Classification of the oocyte is important because the two groups have different requirements for optimum maturation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree