CHAPTER 25 Hyperthyroidism and the Kidneys

RENAL FUNCTION IN HYPERTHYROIDISM

Hyperthyroidism and chronic kidney disease are two of the most common disorders in feline medicine. Almost 30 per cent of cats over 15 years of age have chronic kidney disease,1 and that estimate probably is conservative. Since the initial reports in 1979, hyperthyroidism has increased steadily in incidence, and it is widely considered the most common endocrine disorder diagnosed in cats over 8 years of age.2 Although it is not surprising that two such common disorders as hyperthyroidism and chronic kidney disease can occur simultaneously in a given cat, it was not until the mid-1990s that investigators showed a clinically important interaction between the two diseases.3–5

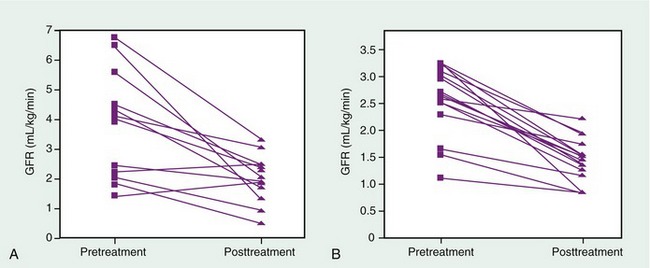

At present it is well established that hyperthyroidism is associated with increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in cats, and that GFR declines after treatment of hyperthyroidism. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, it is likely that increased cardiac output and decreased peripheral vascular resistance associated with hyperthyroidism cause increased GFR by enhancing renal plasma flow.6,7 In normal animals GFR remains constant across a wide range of mean arterial pressures, but this renal autoregulation apparently is lost in cats with hyperthyroidism. Similarly human patients with hyperthyroidism, and experimental animals treated with excess thyroid hormone, experience increased renal plasma flow and GFR.8 It is not known if the thyrotoxic state is directly harmful to the kidneys, but renal insufficiency does not ensue after treatment of thyrotoxicosis in people or after withdrawal of thyroid hormone in experimental animals. On the other hand, many cats develop overt renal insufficiency after treatment of hyperthyroidism (Figure 25-1). The reason is not established, but it may be that the increased GFR associated with hyperthyroidism can mask underlying renal insufficiency in a cat with both disorders. Upon reversal of the hyperthyroid state, renal blood flow and GFR decline, and renal insufficiency becomes more readily apparent. In one recent study 15 per cent of hyperthyroid cats developed overt renal insufficiency within 13 to 18 months of radioiodine therapy.9 Other studies have shown posttreatment renal insufficiency in 17 to 38 per cent of hyperthyroid cats treated by a variety of methods.3–5

DIAGNOSIS OF HYPERTHYROIDISM IN CATS WITH KIDNEY DISEASE

Hyperthyroid cats with underlying kidney disease can present a diagnostic challenge. Multiple diseases can occur simultaneously in older cats, and nonthyroidal illness is thought to be one reason for the increasingly common finding of occult hyperthyroidism. The term occult hyperthyroidism refers to a condition in which clinical hyperthyroidism exists in the face of normal serum total thyroxine (TT4) concentrations. Serum TT4 concentrations are in the normal range in nearly 10 per cent of cats with hyperthyroidism overall, and in up to approximately 40 per cent of cats with mild hyperthyroidism.10 Concurrent disease is a common finding in cats with occult hyperthyroidism; underlying kidney disease can falsely lower serum thyroid hormone concentrations, making a diagnosis of hyperthyroidism more difficult. In a large study of cats with nonthyroidal illness, serum TT4 concentrations were below the normal range (less than 10 nmol/L) in almost 50 per cent of euthyroid cats with kidney disease.10 If the presence of kidney disease is associated with a marked reduction in serum TT4 concentrations in euthyroid cats, it seems reasonable that serum TT4 concentrations could be reduced in a cat with hyperthyroidism in addition to renal disease.

Measurement of serum concentrations of free thyroxine (FT4) is thought to be a more sensitive test for feline hyperthyroidism than measurement of TT4. Evaluation of FT4 concentrations, however, may have unexpected pitfalls in cats with concurrent renal and thyroid diseases. In a recent report, serum FT4 concentrations were high in 20 per cent of euthyroid cats with chronic kidney disease.11 However, the cats all had TT4 concentrations in the lower half of the normal range or lower. Based on that study and others, therefore, measurement of FT4 is not recommended as a sole diagnostic test for hyperthyroidism in cats because of the high probability of arriving at a false-positive diagnosis.

CAN POSTTREATMENT RENAL INSUFFICIENCY BE PREDICTED?

Because GFR is increased in cats with hyperthyroidism, serum concentrations of creatinine are lower than they would be in the euthyroid state. For this reason serum creatinine concentration in a hyperthyroid cat can be even less useful an indicator of GFR than in a normal cat. Similarly blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration is a less useful indicator of GFR in a cat with hyperthyroidism. In hyperthyroidism BUN production is increased markedly because of excessive protein catabolism. Increased BUN/creatinine ratios have been reported in hyperthyroid people,12 and also can be seen in many cats with hyperthyroidism. In our hospital we have observed elevations in the BUN/creatinine ratio not only in hyperthyroid cats compared with normal cats, but also in cats with occult hyperthyroidism when compared with normal cats (Table 25-1). BUN/creatinine ratio can not be used as a test for diagnosis of hyperthyroidism, but an elevated ratio could increase the clinical index of suspicion of the disease in a cat with a normal serum concentration of TT4 (i.e., occult hyperthyroidism).

Table 25-1 Concentrations of BUN and Serum Creatinine and BUN/Creatinine Ratios in Normal Cats vs. Cats with Occult Hyperthyroidism

| Normal Cats (n = 17) | Cats with Occult Hyperthyroidism (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| BUN (mg/dL) | 21.2 ± 3.9* | 28.3 ± 5.0* |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| BUN/Creatinine | 15.5 ± 2.7 | 23.6 ± 5.8* |

Results are expressed as Mean ± SD.

* Denotes statistically significant difference.

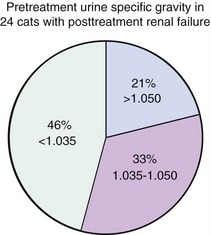

It is often stated that urine specific gravity (USG) can be used as an indirect indicator of renal sufficiency, and that cats with USG greater than 1.035 are less likely to suffer from renal insufficiency after treatment for hyperthyroidism.2,13 Our studies of groups of cats that either did or did not develop renal insufficiency after treatment of hyperthyroidism, however, found that USG can not be used to predict the effect of treatment on renal function.14 Figure 25-2 shows pretreatment USG data from cats experiencing renal insufficiency after treatment of hyperthyroidism. USG was greater than 1.035 in 54 per cent of the hyperthyroid cats who developed posttreatment renal insufficiency, and there was no statistically significant difference in USG between those cats who did and did not develop renal insufficiency.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree