Chapter 9 HORMONE THERAPY IN THE MARE

MANAGEMENT/MANIPULATION OF WINTER ANESTRUS

Artificial Lights

The use of a stimulatory artificial photoperiod remains the main means of controlling the onset of the breeding season in mares. Once mares enter winter anestrus, approximately 60 days of a stimulatory artificial photoperiod, mimicking the long summer days, are required before the onset of the transitional period and the first ovulation occurs.1,2 Typically 16 hours of total light are used, beginning in November or December, with the additional light added at the end of the day. However, the photosensitive window of the mare is approximately 10 hours after the onset of darkness. A single hour of light beginning 9.5 hours after the onset of darkness may also be used in what is called a “flash” lighting protocol. The energy of the light is also important; 100 lux is recommended, but there is a dose-dependent response, with as little as 10 lux having some effect in mares.

Dopamine Antagonists

Dopamine antagonists result in increased secretion of prolactin. The mechanism of action of dopamine antagonists is unknown but may relate to a decrease in dopamine-receptor binding on the ovary or indirect effects of increased prolactin concentrations on ovarian function that have a positive influence on follicular development. Protocols describe the use of increased photoperiod beginning in anestrus/early transition for 2 weeks and then continuing the increased photoperiod while adding a dopamine antagonist such as sulpiride (1 mg/kg IM BID) or domperidone (1.1 mg/kg PO SID) daily for 3 weeks or until ovulation. There is some information that combining 2 months of artificial photoperiod with a 10-day pretreatment with estradiol benzoate (11 mg IM SID/mare) may help prime mares to respond to sulpiride (250 mg SQ SID/mare) therapy.3–5

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone

The physiologic mechanism behind gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) therapy in seasonally anestrous mares is the stimulation of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) synthesis and release from the anterior pituitary, which in turn induces follicular development and ovulation, respectively. Several recent studies have demonstrated that GnRH can be used successfully to induce ovulations in seasonally anestrous mares when administered as hourly pulses of native hormone, twice-daily boluses of a potent agonist or serial insertion of slow-release implants. Products such as deslorelin implants have been used in anestrous/transitional mares. The mares receive a new implant every 3 days for up to 3 weeks or until they ovulate. Injectable deslorelin has been used twice daily (63 μg IM BID) to induce follicular activity in anestrous/transitional mares. Ovulations occur in approximately 50%–70% of anestrous mares treated. The duration from the onset of treatment to ovulation is approximately 2 weeks. Because of the insensitivity of the anestrous/transitional mares to GnRH, implants are not typically removed in anestrous mares. Deslorelin implants have been associated with a delayed return to estrus in some mares during the breeding season when the implants were not removed.6

Overall, however, progesterone concentrations and duration of the luteal phase following GnRH-induced ovulations are similar to those following ovulations that occur during the physiological breeding season. Mares in deep anestrus at the onset of any GnRH treatment may return to anestrus following the end of treatment, even if ovulation was induced. The failure of some non-pregnant mares to continue cyclic ovarian activity after GnRH treatment in anestrus makes it imperative that the mare be monitored carefully for follicular development and ovulation and bred to a stallion of normal fertility. Pregnancy rates following ovulations induced by GnRH in seasonally anestrous mares range from 51% to 80% and are not significantly different than pregnancy rates following the first spontaneous ovulation of the year.6,7 Injectable superagonists, such as buserelin, are more potent and are similar to deslorelin in activity. They are not commercially available in North America at this time, but they appear to have reduced efficacy in the mare.8

Equine Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

Equine follicle-stimulating hormone (eFSH) has been used with good success in mares in early transition. Mares with a 20- to 25-mm follicle are treated with twice daily injections of eFSH (12.5 mg IM) until one or more follicles reaches 35 mm. The eFSH treatment is discontinued, and 36 hours later the mare is treated with hCG and bred. With this protocol the majority of mares continue to cycle following treatment, and ovulation rates are enhanced.9

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), obtained from the urine of pregnant women, is commonly used in veterinary practice to hasten ovulation in transitional and normally cycling mares. hCG is used to shorten the transitional period by stimulating the ovulation of large dominant follicles. In the absence of hCG treatment, many of these large follicles will regress without ovulation and will be replaced by development of another follicular wave that may or may not progress to ovulation. Finally, hCG has also been reported to induce the ovulation of large follicles stimulated to develop in anestrous mares by GnRH administration.10

The biochemical composition of hCG is similar to equine LH but has a much longer half-life because of a high sialic acid content. All gonadotropic hormones have an alpha and a beta subunit, of which the beta subunit is species specific. Various authors have expressed concern about the antigenic nature of hCG in the mare. Antibodies to hCG have been measured in the mare, and frequent hCG treatments in the same breeding season were associated with higher titers. Some researchers have reported a decreased response to hCG following frequent hCG treatments in the same season. It was inferred without measuring antibody titers that antibodies to hCG were causally related to the reduced response. Other authors reported seasonal changes in the mare’s response to the hormone. Critical studies to address the hCG antibody relationship with response to hCG remain to be performed.11

Seasonal factors also influence the time to ovulation from treatment and the percentage of mares ovulating in relationship to hCG administration. A response to treatment with hCG is defined as ovulation within 48 hours of injection. The range of response is variable with a low percentage (12%) of mares ovulating by 24 hours, the majority by 36 hours (50%), and then some by 48 hours (12%) or beyond. Similar to other hormonal treatments, some mares do not respond to hCG.12 In groups of mares, a 75% response rate with ovulation within 48 hours is usually reported. Reduced efficiency of hCG is found in mares treated to end transition. Mares that fail to respond to hCG during the breeding season tend to repeat the behavior and usually ovulate later (72–96 hours after treatment). Commonly used dosages are 2000 to 2500 IU, intravenously or intramuscularly. Interestingly, most mares will ovulate with much lower dosages (500 IU) of hCG.

Progesterone/Progestagen

Late transitional mares with follicles of 25 mm may be placed on altrenogest (Regumate) for 2 weeks or a 1.9-gm progesterone-containing controlled intravaginal device (CIDR) may be inserted for 2 weeks to stop the signs of heat and increase the likelihood of fertile mating. The mare should be evaluated at the end of the progestagen treatment to assess the ovarian status. The use of the CIDR in transitional mares has been variably associated with an increase in follicular development.13

Melengestrol acetate has been used in mares in late transition at 150 mg PO/mare/day for 10 days with a mean time to ovulation after the end of treatment at 14 days. The effect of this hormone on fertility has not been examined.14

Circularized forms of recombinant equine LH have recently been investigated. The most effective dose appeared to be 0.75 mg IM. This is a non-antigenic product that appears to have the similar efficacy to hCG.15

INDUCTION AND SYNCHRONIZATION OF ESTRUS

Estrus synchronization in horses has been problematic because of the long duration of behavioral estrus and the variable time frame to ovulation during estrus. Box 9-1 shows the options for estrus synchronization. There are three methods of estrus induction for breeding: physical aspiration of follicles, induction of luteolysis (prostaglandin F2α [PGF], cloprostenol), and the prevention of estrus with exogenous progesterone (long-acting progesterone, CIDR)/progestagen (altrenogest)/progesterone and estradiol (PGE), which allows natural luteolysis to occur. It is important to remember that progesterone/progestagen administration does not prolong the lifespan of the CL, nor does it suppress luteolysis. Progesterone supplementation induces diestrous-type behavior, even in the mares that undergo natural luteolysis while being treated. The diestrous behavior is of benefit in performance mares, because they neither attract nor are attracted to stallions. Progestagen/progesterone therapy is almost always combined with an ovulation induction treatment such as hCG or GnRH analog (deslorelin).

Box 9-1 Hormonal Options for Induction and Synchronization of Estrus

Altrenogest 10 ml (0.044 mg/kg) PO daily for 8–14 days

Progesterone-in-oil (50 mg/ml) IM daily for >8 days

Long-acting (LA) progesterone single injection IM (activity 8–10 days)

Controlled intravaginal drug release (CIDR) devices 8–14 days, 1.9 g progesterone total per device

Progesterone 150 mg/estradiol 10 mg preparations (P&E) IM daily for 8–10 days

Prostaglandin F2α 1–5 mg once >5 days after ovulation SQ 1–2 injections

Cloprostenol (Estrumate) 125 μg SQ once >5 days after ovulation

Progesterone/Progestagen Therapy

On the last day of progesterone/progestagen treatment, the mares should be given prostaglandin because most of the mares will have functional luteal tissue. They may have luteal tissue from a previous ovulation or they may have ovulated while being treated (in which case they would not show estrus). The main population of treated mares should come into heat on average in about 3 days from discontinuing the administration of the progesterone/progestagen compound, which is also 3 days after prostaglandin treatment. There is wide variability in the onset of estrus from the time the progesterone/progestagen is discontinued, with a range of 1 to 7 days. The reason is that while the progesterone suppresses estrous behavior, it does not suppress follicle development. A failure to come into heat is either behavioral or the mare ovulated late during the treatment and her CL was not sensitive to the prostaglandin.16,17 For this reason evaluating mares for follicular size on the day PGF is given is strongly recommended to determine how fast they should come into heat. Studies show that treatments with altrenogest, long-acting progesterone, or CIDR have a similar mean time to ovulation after discontinuing treatment. Long-acting progesterone is effective for 8–10 days. The CIDRs have 14 days of progesterone-releasing activity, but they may be used for as few as 8 days. The cost and convenience factor are most important when choosing a progesterone/progestagen product. Mare temperament and intramuscular irritation may be an issue if many injections or long-acting formulations are used. It has been indicated that a sustained release injectable altrenogest product may be available in the future. Mild vaginitis has been reported in mares treated with CIDR, and these devices are not recommended for use in subfertile mares.

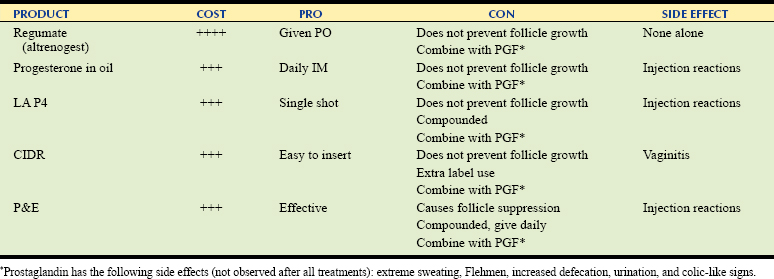

The most effective therapy to induce synchronous estrus and ovulation involves the administration of progesterone and estradiol 17-β (P&E). Other forms of estrogen have not been shown to be effective. The P&E is a compounded product produced as a 50-mg/ml solution of progesterone and a 3.3-mg/ml solution of estradiol 17-β. Three ml of this solution are injected every day for 8–10 days. The addition of estradiol 17-β to progesterone treatment is sufficient to cause follicular regression. Similar to the other progesterone/progestagen treatments, if the mare is in estrus when the treatment is started she may ovulate in the first few days of P&E treatment. Neither hormone is luteolytic; therefore, prostaglandin is also used on the last day of this protocol. The mean time to estrus from the last day of P&E plus PGF injection is 8–10 days. These mares are usually evaluated 6 days after the last treatment to predict the onset of estrus and planned breeding. This protocol is often effectively used by rural practitioners to reliably induce estrus in mares. For example, a mare is examined and the P&E is prescribed for 8 days. The mare is checked at the end of treatment and given prostaglandin. The mare is administered prostaglandin on the last day of P&E treatment. She is then scheduled for an examination 6 days later. At that examination follicle size is measured and, assuming follicles grow at 3 mm/day, semen is ordered to arrive when the follicle is around 35 mm. The mare is injected with hCG on the day before or at the time of the breeding.11 The pros and cons of progesterone/progestagen therapy are summarized in Table 9-1.

Prostaglandin

The clinical use of PGF includes its use to “short cycle” a mare. PGF (5 mg/mare SQ) and its analogs, such as cloprostenol (125 µg/mare SQ),10 are one of the most affordable and most widely used products in equine practice. They are used to cause regression of a CL from days 5 to 16 of the estrous cycle (day 0 is ovulation). Prostaglandin has few ovarian effects if administered in estrus but causes some sustained uterine contractions, which is why it is sometimes administered to subfertile mares before ovulation. When repeated doses of PGF are administered prior to 5 days post-ovulation, luteolysis will occur; however, the mare will not come into heat faster unless the mare is a two-wave mare and already has a medium-sized follicle. Two low-dose injections (0.5 mg/mare IM) spaced 12 hours apart are also effective in inducing luteolysis and are associated with fewer side effects.11,16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree