Chapter 80 Hoof Disorders in Nondomestic Artiodactylids

Zoological institutions commonly exhibit nondomestic artiodactylids, or even-toed ungulates, because of their public appeal, educational value, and conservation message. These hoofed herbivorous mammals include the pigs, peccaries, hippopotami, camels, chevrotains, deer, giraffes, pronghorn, antelopes, sheep, goats, and cattle species.15,20 Ungulates also include hoofed animals with an odd number of toes, or Perissodactyla (horse, tapir, rhinoceros), but are not discussed in this chapter.

Because of the variety in body size, coat color, and personality, nondomestic artiodactylids are charismatic and represent the diversity of the animal kingdom. Many adaptations are present in the hoof structure of these ungulates and reflect the contrasting natural environments in which they are found. Desert-dwelling species such as the addax (Addax nasomaculatus), with hard, widely splayed hooves for travel in the sand, are readily differentiated from the elongate hooves and soft leathery heels adapted for traversing wetlands and bogs by species such as the sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekeii).20 Thus, the zoo veterinarian must recognize species differences and understand the range of normal structure and function of the nondomestic artiodactyl hoof. Anatomically, the foot of a two-toed artiodactyl is described as the limb distal to the fetlock joint but the focus of this chapter will be limited to the horn covered structure, interchangeably called the hoof or claw.

Just as in the domestic cow, sheep, goat, and pig, normal hoof structure may be compromised because of trauma, infection, or poor conformation, leading to clinical problems in nondomestic artiodactylids.* In my practice, hoof disease is a common cause of lameness and morbidity, which without proper medical attention may result in fatal consequences. Despite the clinical importance, specific epidemiologic information on hoof health and diseases is lacking in the nondomestic animal literature.

An encyclopedic review of hoof disorders is beyond the scope of this chapter and the reader is directed to the many excellent veterinary references on the ungulate foot found on the domestic hoofstock library shelf. Extrapolation from a domestic prototype species is a familiar and clinically useful concept to the zoo and wildlife veterinarian. Because detailed information on hoof disorders does not exist on the approximately 220 species of nondomestic artiodactylids,15,20 it is reasonable for their domestic cousins to serve as valid references for basic anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, diseases, and treatments of the hoof. The objective of this chapter is to provide the veterinarian with practical clinical review of the cause, diagnosis, and management of the common and unique hoof problems in nondomestic artiodactylids under their care.

Functional Anatomy of the Hoof

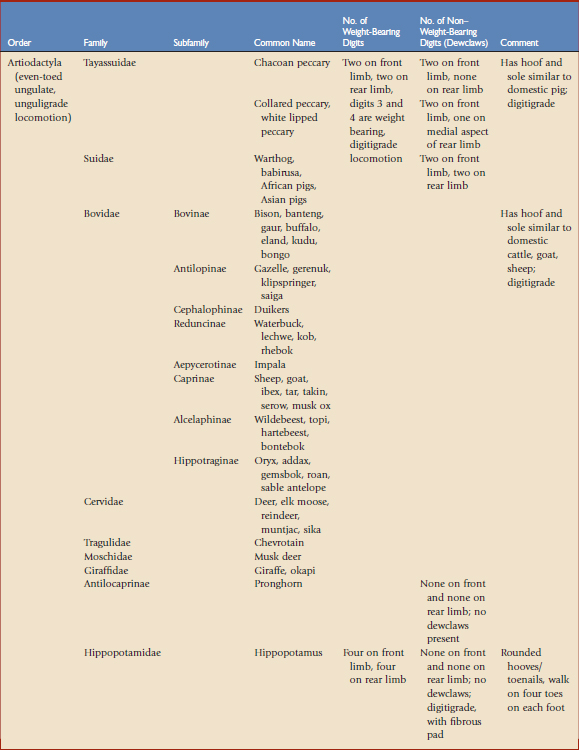

It is important to understand the normal anatomy of the hoof to recognize, treat, and prevent common and uncommon diseases. The basic function of the hoof reflects an adaptation to minimize weight-bearing stress and protect it from injury and pathogens in the animal’s natural environment. Most nondomestic two-toed ungulates have foot anatomy similar to that of cattle, sheep, goat, and swine.4,20,22,23 Hippopotami, however, do not fit this classic description.7,13 The hippopotamus has a widespread foot with four weight-bearing digits. Table 80-1 reviews the foot structure and number of weight-bearing digits in the nondomestic artiodactylid. The primary distinguishing feature of artiodactylids is the paraxonic limb structure, in which the symmetry of the foot passes between two well-developed middle digits. The first digit is absent in all ungulates. The third and fourth digits are weight bearing, whereas the second and fifth are reduced, vestigial, or absent. Bovids are differentiated from other terrestrial animals by unguligrade locomotion, in which only a hoof or claw (the tip of one or two digits) touches the ground.

The bovine hoof is well described in the literature22,24 and will be used as a prototype to describe its microscopic and macroscopic anatomy. The hoof, or claw, is descriptively composed of the coronary band, adjacent skin, horned wall, sole, lamina, heel, and encased bone of the distal or third phalanx (P3). Rear limbs are rigidly fixed to the body at the ball and socket of the hip joint, whereas the front limbs are more flexibly connected to the torso by soft tissue (muscle, ligaments, tendons). This biomechanical difference is proposed as a potential explanation for the more common lameness noted in the rear limbs of dairy cattle when compared with the front limbs. The hoof grows distally from the coronary band at a rate of approximately 5 to 7 mm/month in cattle but is dependent on genetics, weight distribution, environment, nutrition, and exercise. The outer claw of the rear foot grows more rapidly than the inside claw, whereas the inner grows more rapidly than the outer on the front foot. The heel, also called the bulb, functions as a shock absorber to normal compressive forces.

The lamina in bovid species is not as extensive as in the horse, but is a unique and important structure deserving special attention.23 It is analogous to the dermis and consists of connective tissue and a rich supply of vasculature and nerves. The lamina provides a strong but flexible attachment between the weight-bearing bone of the third phalanx with the hard wall of the claw. Adjacent to the lamina, and moving outward to the claw surface, are the basement membrane, germinal epithelium, stratum spinosum and, finally, the outer horn layer, the stratum corneum. The interdigitating junction of dermal and epidermal laminae act as a suspensory apparatus between the bone and horny wall and is extremely sensitive to physical or vascular disturbances. The germinal epithelium is the active region of cell proliferation and differentiation. These cells differentiate into keratinocytes that produce and accumulate keratin proteins as they migrate away from the germinal epithelium, losing their supply of nutrients and oxygen. Keratinocytes then undergo a process of death and cornification, forming the cells of the tough outer horn of the claw that serves to protect inner structures and support the weight of the animal. Undoubtedly, any disorder that disrupts blood flow to the lamina will eventually have an effect on the integrity and health of the horny wall of the hoof or sole. Also of clinical significance, the rigid wall of the hoof precludes natural swelling of inflamed tissue, resulting in increased interstitial pressures, which may be greater than vascular pressures that cause obstruction to blood flow, with potential pathologic consequences.

Causes of Hoof Disorders in Nondomestic Artiodactylids

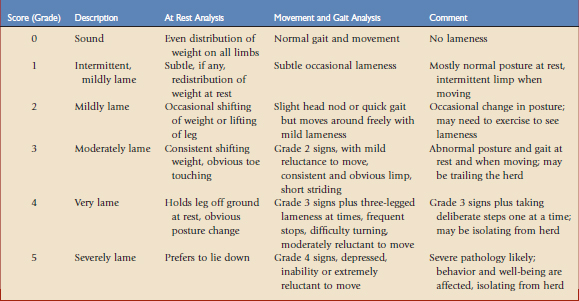

Lameness is defined as any condition that inhibits or modifies the gait of an animal and is typically the most obvious clinical sign of a hoof disorder. There are many causes of lameness that may originate in any anatomic structure of the limb, but the discussion here is limited to the hard and soft tissues of the hoof. Just as in domestic hoofed animals, lameness caused by disruption of hoof wall and sole integrity from physical trauma, laminitis, and infection is a common disorder in my nondomestic artiodactylid practice. Therefore, a lameness scoring system, adapted from the literature,22 is used by the veterinary and animal care staff to provide consistency in description, documentation, and communication of lameness problems (Table 80-2). Although most lameness is caused by pain, nonpainful causes such as those that restrict normal biomechanics (e.g., fibrosis, arthrodesis, pregnancy) or neurologic dysfunction may mimic lameness and should be considered. Any persistent or significant lameness should not be neglected.

There are many predisposing factors that potentially contribute to hoof disorders in captive nondomestic artiodactylids. Enclosures with adequate space must be properly and carefully designed, with the natural history and welfare of the species in mind. Exercise promotes natural control of hoof growth while providing ideal circulation and nutrient delivery to the tissues of the hoof. Wire fences and other potentially harmful exhibit perimeters may cause traumatic wounds to the hoof and interdigitum of species known to jump and climb (e.g., nondomestic goat and sheep). Similar considerations must be made for hospital and temporary holding facilities. Poor nutrition and improper substrate (hard, soft, wet, dry) are recognized as contributing to hoof problems in domestic animals,1,16,18,24,25 and similarly affects our collection artiodactylids. Excess moisture weakens the protective properties of the hoof and sole, which increases susceptibility to bruises, abscesses, and laminitis. Exhibition of certain species should be avoided if climatic and seasonal housing needs cannot be met. Poor living conditions and lack of hygiene predispose animals to many health problems, including those of the hoof. Hoof infections are commonly related to environmental conditions and increased abundance of causative organisms.17 As noted, the inability to perform routine hoof evaluations and trims in noncompliant species may also jeopardize hoof health by allowing secondary hoof infections to occur. Healthy epithelium and horn tissue are naturally resistant to infections so any breach may increase susceptibility. Refer to Box 80-1 for review of potential hoof problems, by anatomic location, in the nondomestic artiodactylid.

BOX 80-1 Disorders of the Hoof in Nondomestic Artiodactylids by Anatomic Foot Location

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree