CHAPTER 26 Home Monitoring of Blood Glucose in Cats with Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is a common endocrine disease in cats. A recent study reported an increase in hospital prevalence over 30 years from 0.08 per cent in 1970 to 1.2 per cent in 1999.1 Currently it is assumed that approximately 80 per cent of these cats suffer from type 2–like diabetes, which is characterized by a combination of insulin resistance by peripheral tissues and liver and of β-cell failure. High blood glucose itself has negative effects on β-cell function and insulin sensitivity, a phenomenon called glucose toxicity. Immediate treatment may reverse these effects, at least in part, and the diabetes may go into remission. Remission usually occurs during the first 3 months of therapy; however, it may take 1 year or longer.2 The possibility of diabetic remission is one of the reasons why close supervision and regular measurement of blood glucose is paramount. If remission occurs unnoticed and the administration of insulin is not discontinued, serious hypoglycemia may result.

Successful treatment requires that the owner be highly motivated and collaborate closely with the veterinarian, who should follow a precise protocol. Box 26-1 gives a brief overview of the protocol used in our hospital.

AT THE TIME OF DIAGNOSIS

RECHECK IN HOSPITAL 1 WEEK AFTER DIAGNOSIS

RECHECK IN HOSPITAL 3 WEEKS AFTER DIAGNOSIS

RECHECK IN HOSPITAL 6 TO 8 WEEKS AFTER DIAGNOSIS

RECHECK IN HOSPITAL 10 TO 12 WEEKS AFTER DIAGNOSIS

MONITORING IN THE HOSPITAL

Fructosamine is the product of an irreversible reaction between glucose and the amino groups of various serum proteins, and its concentration reflects the mean blood glucose concentration of the preceding 1 to 2 weeks. Reference ranges differ slightly among laboratories but usually are around 200 to 360 µmol/L. In most cats with newly diagnosed diabetes, fructosamine levels are higher than 400 µmol/L and may be as high as 1500 µmol/L. Normal fructosamine levels may be seen in cats with a very recent onset of diabetes and in diabetic cats suffering from concurrent hyperthyroidism or hypoproteinemia.3–5 Fructosamine concentrations increase when glycemic control worsens and decrease when glycemic control improves. Because even well-controlled cats are slightly to moderately hyperglycemic throughout the day, fructosamine concentration usually will not decrease into the normal range. Accordingly a normal fructosamine concentration (particularly a fructosamine value in the lower half of the reference range) should raise concern about prolonged periods of hypoglycemia (e.g., insulin overdose, diabetic remission).

SELF-MONITORING OF BLOOD GLUCOSE IN HUMAN BEINGS WITH DIABETES MELLITUS

In the late 1970s self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) was introduced in human medicine.6–8 For SMBG human patients obtain a drop of capillary blood, usually by pricking a fingertip, with the aid of a lancing device. The drop then is placed on a test strip, and the glucose concentration is measured using a PBGM. The sampling process is simple and has become relatively painless with the use of newer generations of lancing devices. The introduction of SMBG is regarded as the single most important advance in the management of diabetes since the discovery of insulin.9 Today all diabetes treatment guidelines include SMBG as an integral part. Diabetic individuals (type 1 and 2) treated with insulin are advised to perform SMBG several times daily, and regular monitoring also is recommended in diabetics treated with oral hypoglycemic drugs or diet only.10 More frequent SMBG is associated with better metabolic control, which in turn decreases the incidence and slows the progression of complications of long-standing diabetes.9,11–13 SMBG has made it possible for patients to obtain immediate and precise feedback on their blood glucose concentration, allows them to understand the impact of food choices, physical activity, and concurrent illness, and gives them control of their disease.

For human beings who find pricking a fingertip unpleasant, alternative site testing has been developed. Those sites where pricking may be less painful include the upper arm, forearm, base of the thumb, tip of the earlobe, and the thigh. Blood glucose levels obtained from alternative sites may differ slightly from those obtained from the fingertips.14,15

HOME MONITORING OF BLOOD GLUCOSE BY CAT OWNERS

BLOOD SAMPLING TECHNIQUES

Until a few years ago SMBG in diabetic pets was not thought to be feasible. However, several methods have been developed recently to obtain capillary blood by means of lancing devices manufactured for human patients. In 2000 two methods of capillary blood sampling from the ear were described.16 One method, which used a conventional lancing device after prewarming the ear with a hair dryer, was applicable only to dogs. The other method, the “Vaculance method,” was based on a new type of lancing device introduced at that time, the Microlet Vaculance (Bayer Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), and it was applied successfully in cats as well as in dogs (Figure 26-1). After lancing the skin the device creates a negative pressure, which enables the sampling of an adequate amount of blood in most instances. The details of the procedure for the Vaculance method are as follows. The tip of the ear is held between the thumb and index finger and the entire surface of the outer pinna is held flat using the remaining fingers of the same hand. With the other hand the lancing device is lightly placed on a nonhaired area of the inner pinna, such that an airtight seal is formed between the end cap of the device and the skin. When the plunger cap of the device is pressed, a lancet moves quickly back and forth one time. Pressure between the end cap and the skin is maintained while the plunger is slowly released. Because of the developing negative pressure, the skin of the ear begins to bulge into the end cap. The formation of a drop of blood is hastened by releasing the pressure exerted by the fingers on the outer surface of the pinna. When an adequate amount of blood appears on the skin, the plunger is pressed down to release the negative pressure and the lancing device is removed. Then the test strip of the PBGM is brought into contact with the blood drop and the required amount of blood is absorbed automatically (Figure 26-2).

The buccal mucosa has been described as another site for capillary blood sampling in dogs.17 This site probably is not feasible in cats. Gums, lips, and footpads also have been mentioned as possible puncture sites,18 but there are no studies that have investigated their suitability in cats. It is not known whether blood glucose levels vary with different sampling sites in cats, as is the case in human beings.

An alternative to capillary sampling is the collection of venous blood from the marginal ear vein. This technique, called the marginal ear vein technique, has been used successfully in diabetic cats.19,20 After localization of the marginal ear vein on the edge of the pinna, the vein is either punctured with a needle or a lancing device. Thompson et al19 reported that a warm gauze sponge applied before puncture increased perfusion, and application of a thin film of petrolatum over the sampling site in long-haired cats allowed a drop of blood to form without dissipating into the fur. Van de Maele et al20 prepared the puncture site in long-haired cats by shaving a small part of the pinna to improve visualization of the vein, and by placing a hard cylinder-shaped object, such as the empty roll from bandage material, behind the ear to provide stability. Afterwards pressure is applied to the punctured area to avoid excessive bleeding.

PORTABLE BLOOD GLUCOSE METER

In human medicine, quality control of PBGMs is of ongoing concern. Factors that may affect the results of glucose measurements include variation in hematocrit, altitude, environmental temperature and humidity, hypotension, hypoxia, and triglyceride concentration.21 The overall performance of a PBGM depends on the analytical accuracy of the unit, quality of the test strips, and proficiency of the user. The goal of the American Diabetes Association is that all measurements conducted with a PBGM be within 5 per cent of the laboratory value. However, this target is not met currently.22

In veterinary medicine the use of PBGMs has gained great popularity during recent years. They are not only an essential part of the HM procedure, but also are used frequently in veterinary hospitals for routine blood glucose measurements. However, it must be remembered that these devices have been designed for human beings, and most PBGMs currently available have not been validated for use in cats. However, a few studies have investigated the accuracy of PBGMs in cats.16,19,23–25 In two studies PBGM measurements using capillary blood were compared with glucose measurements using venous blood and a reference method.16,25

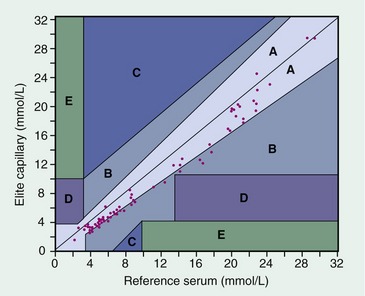

In our own study16 the PBGMs Glucometer Elite (Bayer Diagnostics) and Accu-Chek Simplicity (Roche Diagnostics, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were evaluated. Using error grid analysis,26 all PBGM measurements were in zones A and B, which is indicative of clinically acceptable results (Figure 26-3). The Glucometer Elite was considered the easiest to operate because it has no buttons to press and turns on automatically when the test strip is inserted; it is the PBGM used in our hospital and by our pet owners. In contrast to other PBGMs, which underestimate or overestimate true blood glucose concentrations arbitrarily, the Glucometer Elite yielded underestimations consistently. In 2002 Bayer changed the brand name of their glucose monitor line, and the Glucometer Elite was renamed Ascensia Elite. Zeugswetter et al25 compared capillary blood glucose values measured by the PBGM FreeStyle Freedom (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) with venous blood glucose values measured by the reference method. The former were a mean of 32 mg/dL lower than the latter, and the error grid analysis showed that 96 per cent of the data measured with the PBGM were in zones A and B, and 2 per cent each were in zones C and E. Values in the latter zones are not acceptable from a clinical point of view.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree