Chapter 8. Histopathology, Immunohistochemistry, and Tumor Grading

Elizabeth M. Whitley

PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF BIOPSY SUBMISSION

History

The signalment and historical narrative given at the time of sample submission provide the framework in which the pathologist views a case. A complete, concise history is a tremendous aid to the pathologist and, in some cases, is critical for arriving at an accurate diagnosis. A gross description and diagram of the anatomic location and shape of the mass help provide a mental image of the lesion. A short description of any previous treatments and the response to treatment should also be included. A comment regarding the etiologic agent or pathologic process suspected is a valuable addition to the history, since it summarizes the clinical impression of the practitioner. Comments regarding any additional tests being performed, such as bacterial or fungal culture, or adjunctive therapies, such as post-surgical cryotherapy, are also useful to the pathologist. Providing case numbers or a copy of the report of previous submissions helps the pathologist follow the disease progression. Finally, if any legal actions are being considered related to the case, it is helpful to alert the pathologist to this fact.

Sample Collection

From the pathologist’s perspective, the larger the sample size, the better the chance of examining an area that will yield an accurate diagnosis. Submission of the entire lesion is preferable. Surgical excisions with wide normal tissue margins will provide more tissue for histologic examination, will allow margins to be examined for presence of tumor cells, and may be curative. If an incisional or core biopsy is to be performed, selection of the biopsy site is crucial. It is critical to avoid areas of necrosis, often found within the center of the mass and characterized by soft, friable, or ulcerated tissue. Instead, multiple samples from the edges of the lesion are preferred and will provide tissue that is more likely to contain viable, proliferating cells with diagnostic architectural features. An exception is when a mass within bone is to be sampled. In these cases, the tissue most useful for biopsy is usually situated near the center of the mass.

Decision-Making for “Difficult” Tumor Types

Splenic Hemangioma and Hemangiosarcoma

Accurate sample site selection for the diagnosis of splenic hemangiosarcoma is notoriously difficult because the major portion of most splenic masses consists of hematoma or necrotic tissue. When sectioning a spleen that contains a hemorrhagic mass, tissue samples from multiple sites should be submitted. The most useful samples typically come from areas that are moderately firm, white to gray-tan (indicating high cellularity), and often at the margins between grossly normal or moderately congested splenic parenchyma and more bloody tissue. Metastatic nodules of hemangiosarcoma are also very useful to the pathologist.

Bony Neoplasms

Failure of core or needle biopsies from suspected bony neoplasms to provide diagnostic quality specimens is usually due to not coring deeply enough into the hard mass to reach the tumor, and instead collecting reactive fibrous or bony tissue. Including a description of the radiographic findings is particularly helpful to the pathologist.

Very Small Sample Size

Samples collected via endoscopy or needle biopsy are very susceptible to crushing artifact and, in some cases, may not be representative of the disease process. Therefore, collection of multiple samples enhances the probability of obtaining useful information by these techniques and will increase diagnostic accuracy. Because of their small size, pieces of mucosal tissues collected by endoscopy are difficult to orient during embedding, sometimes requiring that the paraffin block be melted and the tissues rolled and sectioned again. To facilitate orientation of small samples, they may be placed on a solid support, such as a tongue depressor or thin piece of cardboard, before fixation.

Biopsy Tissue Handling

Handling biopsy samples gently helps to preserve normal tissue architecture. Samples that have had excessive pulling or crushing forces applied will have distorted tissue architecture that may prevent accurate diagnosis or margin evaluation. The use of electrocautery or laser energy causes coagulation of tissues, which results in loss of the fine features of cells.

Identification of Tissues and Margins

Ideally, when multiple samples are submitted, individual specimens should be placed in separate, labeled containers of formalin. Containers should be labeled on the side, instead of the lid, to help avoid mix-up of specimens.

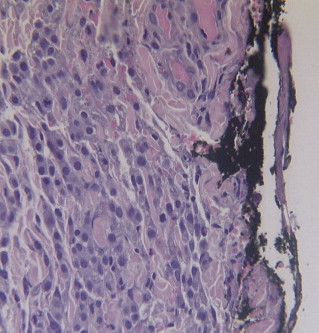

Surgical margins are examined by the pathologist to determine the degree of invasiveness of neoplastic cells and to determine if complete excision was accomplished. To aid in this examination, surgical margins of resected tissue may be marked using a tissue dye, such as waterproof India ink (available at art and office supply stores) or colored inks (Davidson’s Marking System, Bradley Products, Inc., Bloomington, MN). Different-colored inks may be used to mark individual regions of a biopsy sample or to aid in orientation. Surgical margins are easily differentiated from cuts made at the time of sectioning by the thin black line of carbon particles of India ink that line a true surgical margin ( Figure 8-1 ). Suture material may be used to mark areas of interest, but the ends of the sutures sometimes are difficult for the pathologist to find. Leaving long ends of suture material and using colored suture material make these markers easier to locate.

|

| Figure 8-1 India ink may be used to delineate surgical margins as shown here. The black border of India ink on the right margin differentiates surgical borders from artifactual borders created by tissue sectioning when slides are prepared. |

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree