Chapter 7 THE HINDLIMB

The hindlimb has gluteal, perineal, thigh, knee or stifle, crural, tarsal, metatarsal and phalangeal regions. Bony prominences are readily identifiable: these include the cranial dorsal iliac spine, the greater trochanter and the ischiatic tuberosity. An assessment of the relative positions of left and right hindlimbs allows assessment of fractures of the ossa coxae or hip dislocation. The once thought hereditary condition of hip dysplasia is now thought to be multifactorial in origin, resulting in an overall incongruity of the hip joint rather than just the lack of a proper acetabulum. The degree of abnormality can be assessed by placing the animal in dorsal recumbency and then abducting stifles to see how far they approach the horizontal i.e. the amount of congruency in the hip joint. The Ortalani sign is also used and in this the animal is laid on its side, the stifle abducted and proximal pressure is applied to the hip – the hip can be felt to click as it pops back into the acetabulum.

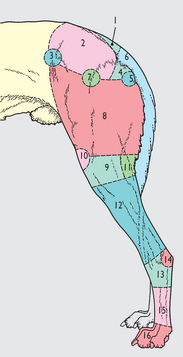

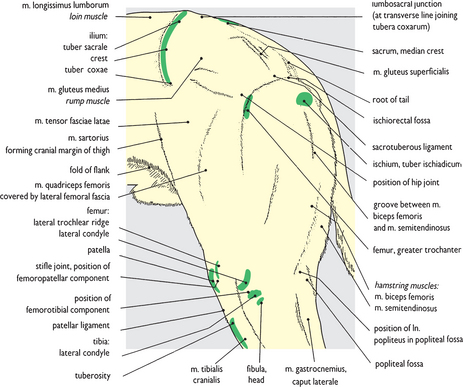

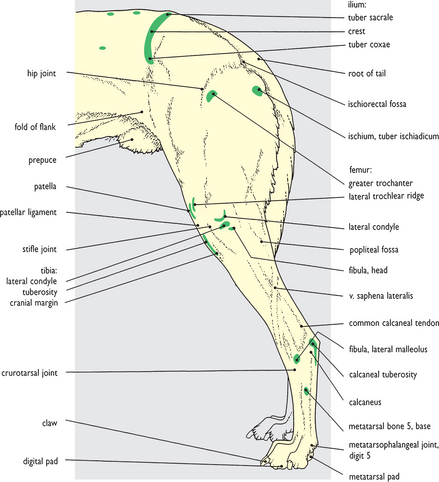

Fig. 7.1 Surface features of the hindlimb: left lateral view. The palpable bony prominences of the hindlimb are shown in this picture. In addition the position of a number of muscles that are readily palpable and/or whose outlines are clearly visible are shown. Although nonpalpable from the surface, the position of the hip joint is indicated by the greater trochanter of the femur which lies lateral to it. In the lower part of the leg the common calcaneal tendon is a well-defined cord terminating on the calcaneal tuberosity (‘point of the hock’). Its three components – gastrocnemius tendon, superficial digital flexor tendon, and accessory tendon from the hamstring muscles – might be distinguishable if the paw is raised, removing tension from the tendon. Fig. 7.1A shows the main topographical regions of the hindlimb based on internal osteological components: the subsidiary topographical regions are related to the underlying joints between segments.

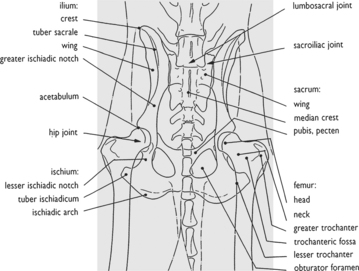

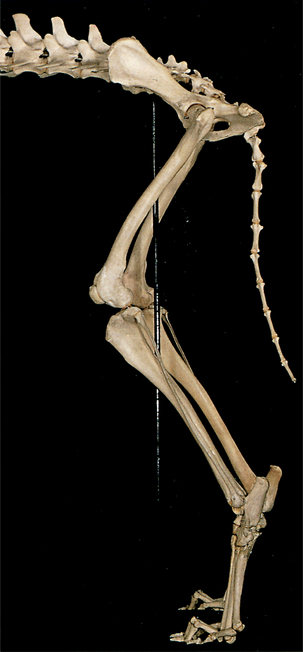

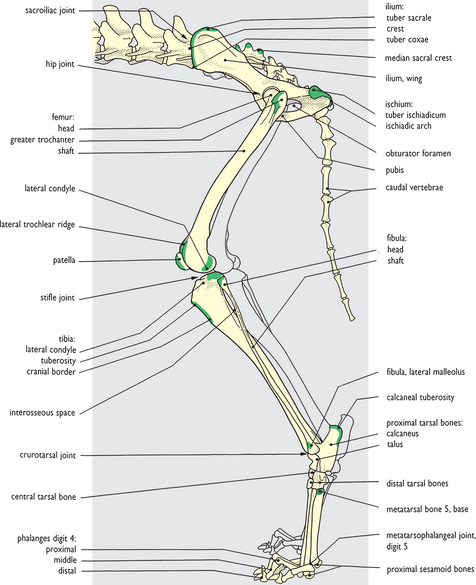

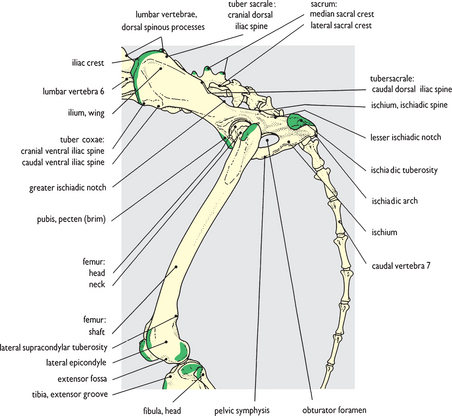

Fig. 7.2 Skeleton of the hindlimb: left lateral view. The palpable bony features shown in the surface view in Fig. 7.1 are colored in the drawing. The adjacent bones of the vertebral column are included in the picture to show the topographical relationships between the two in the normal standing posture. Unlike the forelimb there is a firm bony union between hindlimb and trunk – left and right pelvic bones are joined in a pelvic girdle which is united with the vertebral column through strong sacroiliac joints situated caudomedial to the sacral tuberosities. Each pelvic bone has four developmental components fusing at an early age (2-3 months). The three obvious components (ilium, ischium and pubis) each have palpable features shown here. The fourth component (acetabular bone) is small and located within the acetabular fossa of the hip joint.

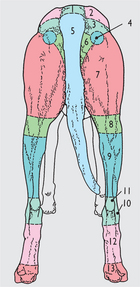

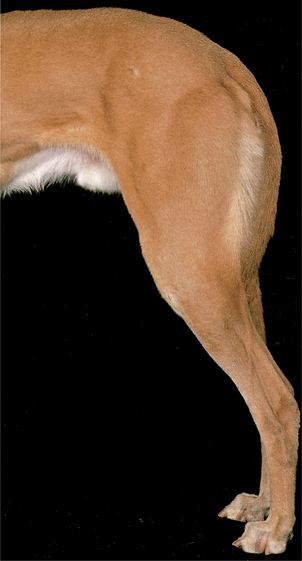

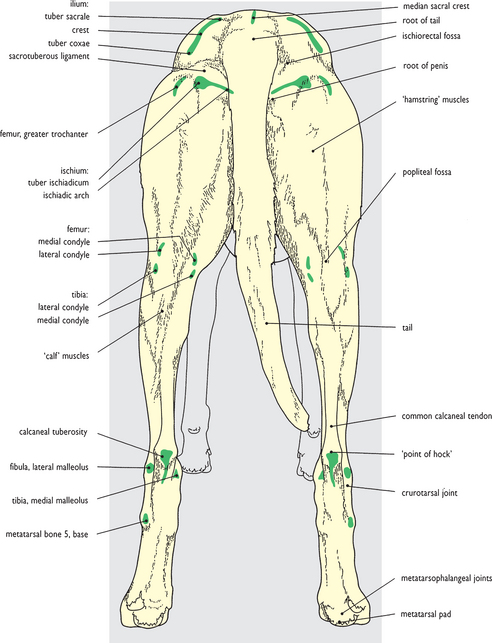

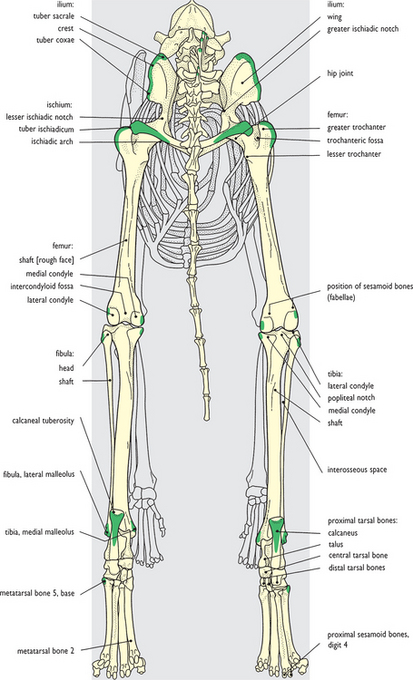

Fig. 7.3 Surface features of the hindlimb: caudal view. The major palpable bony features and topographical regions already noticed in the lateral view of the limb are shown again as reference points and are indicated in the drawing. One or two additional bony prominences palpable on the medial aspect of the limb are also shown. The ischiorectal fossa is a clearly visible and palpable depression lateral to the root of the tail. Lying alongside the anal canal it is normally padded out with fat and would not be quite as readily apparent as it is in the greyhound. A second clearly visible and palpable depression, the popliteal fossa, is caudal to the stifle joint between the diverging lower ends of the hamstring muscles. The large popliteal lymph node can be felt within the fossa. Fig. 7.3A shows the main topographical regions of the hindlimb.

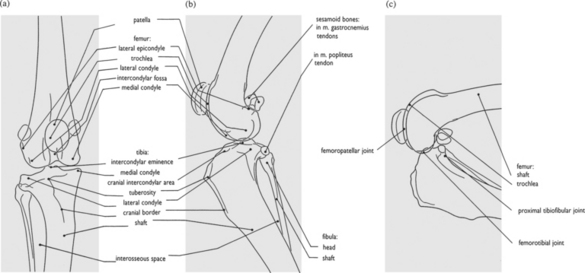

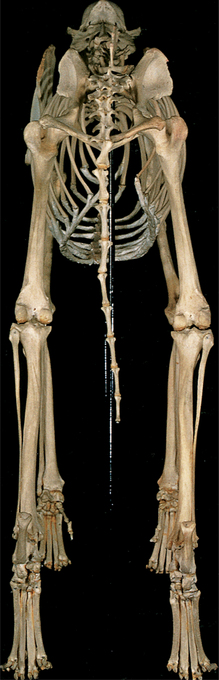

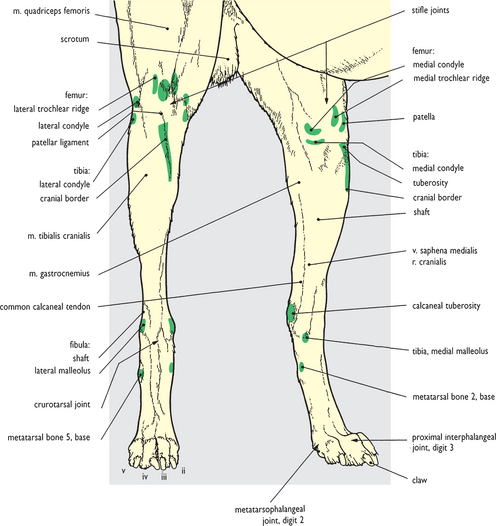

Fig. 7.4 Skeleton of the hindlimb: caudal view. The palpable bony features shown on the surface view are colored in the drawing. In this skeletal preparation the fabellae – sesamoid bones located in the gastrocnemius muscle tendons caudal to the stifle joints – have been lost. The position they would have occupied is shown by smooth articular facets on the caudodorsal aspect of the prominent femoral condyles, and they are clearly displayed radiographically in Fig. 7.10. In the crural region the tibia and much reduced fibula lie side by side, an arrangement in marked contrast to the forearm where radius and ulna, equally well developed, cross over one another. The limited degree of mobility that this forearm orientation imparts to the forepaw is completely lacking in the hindpaw.

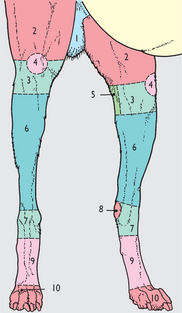

Fig. 7.5 Surface features of the hindlimb: cranial view. The major palpable bony features already noticed in lateral and caudal views are shown again as reference points and are indicated in the drawing. In addition, much of the medial surface of the tibia is subcutaneous from medial tibial condyle at its proximal end down to medial malleolus at its distal end. The position of the crurotarsal joint is identifiable since the ridges and grooves of the trochlea of the talus are palpable alongside the tarsal flexor and digital extensor tendons. Slightly farther distally pulsation within the dorsal pedal artery may be felt at the base of the metatarsal region towards the medial side. Fig. 7.5A shows the main topographical regions of the hindlimb.

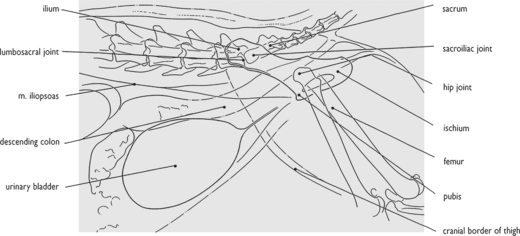

Fig. 7.7 Skeleton of pelvic and femoral regions: left lateral view. The features colored green correspond to the palpable bony features shown in Fig. 7.6.

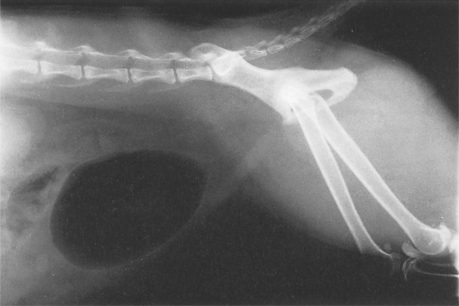

Fig. 7.8 Radiograph of the pelvis and hip joint: left lateral view. The hip joint and pelvis in lateral view is potentially of less anatomical value than the ventrodorsal view (fig. 7.9) since the femoral heads and hip joints are superimposed. However, such a view as this with the hindlimbs pulled caudally demonstrates the considerable overall mobility available to the hindlimbs. This is the sum total of movements at the caudal lumbar, lumbosacral and sacroiliac joints as well as the hip joints themselves.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>