Chapter 36 Hematology and Cytology of Small Mammals

This chapter provides photomicrographs and other information that may be useful during the examination of blood smears and tissue aspirates from selected small mammals. More comprehensive discussions are available elsewhere regarding the evaluation of blood smears from many of these species; these texts are listed among the references.* While knowledge of the plausible differential diagnoses is often critical in the interpretation of cytologic findings, the same general principles of cytology used in dogs and cats can be applied to small mammals. The reference list below includes several excellent veterinary cytology references.†

Most of the photomicrographs in this chapter were taken under immersion oil by using a 100× objective and 10× eyepiece, equaling 1000× magnification. For some lesions, evaluation of cytologic specimens can readily be performed by using the microscope’s 40× objective (high dry, 400× magnification). In fact, this lens can be more useful than the 100× lens because it provides a larger field of view, allowing the examiner to evaluate a larger portion of the slide in less time while revealing compelling cellular details and other features. Nonetheless, many clinicians and technicians are not satisfied with the quality of the resolution of this lens. In defense of the 40× objective, optically it is designed to be used principally with slides that have been cover-slipped. A good technique for temporary placement of a cover slip is to deposit a very small drop of immersion oil on the stained smear and then place a rectangular glass cover slip on the drop of oil. If resolution is then not improved upon examination of cover-slipped material, suspect that the lens may have been inadvertently soiled with immersion oil during previous use. A thorough cleaning of the external surface of the lens can be successful, using several cotton swabs thickly moistened with lens cleaner, followed by extended buffing with several dry cotton swabs. On microscopes used by numerous operators, and particularly those where the 100× (oil-immersion) lens receives heavy use, the 40× lens may require frequent cleaning.

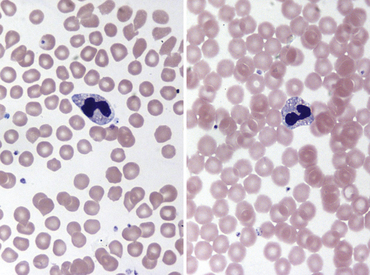

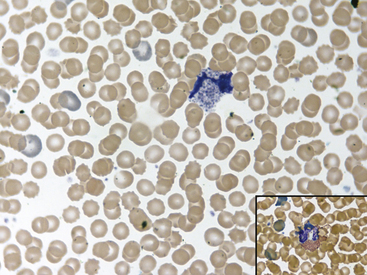

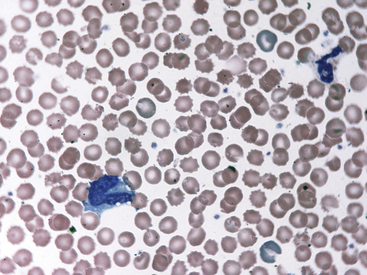

Fig. 36-8 Leukocytes. Peripheral blood smear—guinea pig. This field shows a neutrophil/heterophil (right) and a monocyte (left). The neutrophils of guinea pigs, hamsters, and gerbils are often referred as heterophils or pseudoeosinophils because they contain granules that stain eosinophilic in color with Romanowsky stains, as with the Wright’s-Giemsa method. Heterophils in these species perform similar functions as neutrophils; some clinicians interchange their names. In the guinea pig, eosinophils and heterophils are easily differentiated because of the size and number of the granules (see inset, Fig. 36-7); eosinophils have more numerous and larger round to rod-shaped granules. Eosinophils in many small mammal species often reveal a U-shaped nucleus. Automated hematology analyzers generally incorrectly identify heterophils/pseudoeosinophils as eosinophils.

(Modified Wright’s-Giemsa stain, 1000×.)

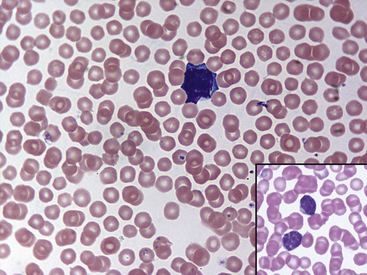

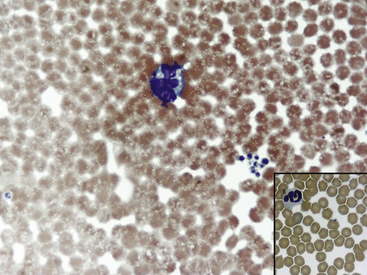

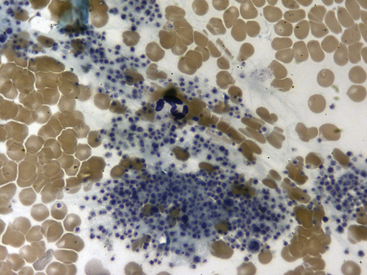

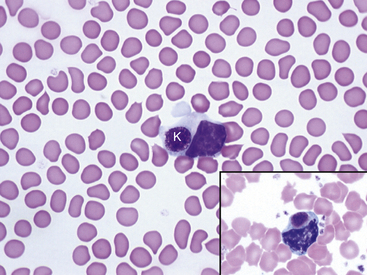

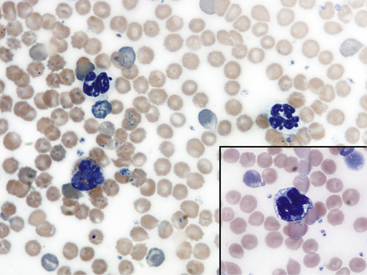

Fig. 36-10 Lymphocytes with Kurloff’s bodies. Peripheral blood smear—guinea pig. These photographs (principal field and inset) show individual lymphocytes, each containing an intracytoplasmic Kurloff’s body, which is reddish-purple and often larger than the adjacent nuclei. Lymphocytes with Kurloff’s bodies (also known as Foa-Kurloff cells) are unique to this species and may account for 3% to 4% of the circulating leukocytes and occasionally more. These structures are found in higher proportions of circulating lymphocytes in young guinea pigs as well as in adult females. Lymphocytes containing Kurloff’s bodies are believed to be analogous to large granular lymphocytes, or natural killer (NK) cells, in other mammals.2,19

(Modified Wright’s-Giemsa stain, 1000×.)

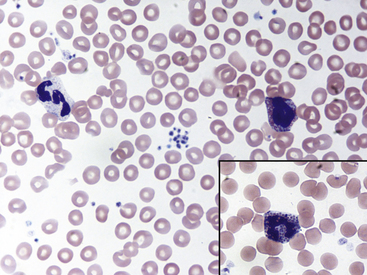

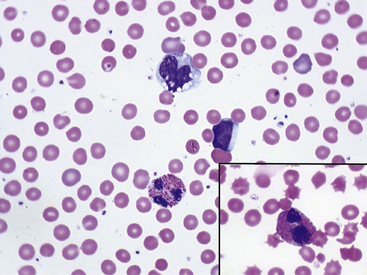

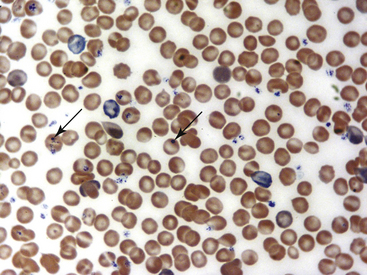

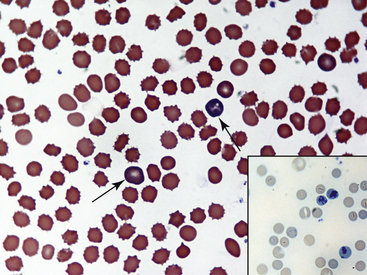

Fig. 36-12 Leukocytes. Peripheral blood smear—mouse. These photographs show two neutrophils and an eosinophil (principal field) and a monocyte (inset) as well as scattered polychromatic red cells. Mature neutrophils of rats and mice generally have a clear-staining cytoplasm, but they may contain a few dust-like reddish granules and appear diffusely pink with Romanowsky-type stains. Granulocytes of rodents often have nonlobulated nuclei; these may be horseshoe- or ring-shaped. Rodent eosinophils show considerably fewer and less distinct granules than those of other small mammals. In rats and mice, an age-dependent variation exists in the neutrophil:lymphocyte (N:L) ratio, with the lymphocyte concentration decreasing and the neutrophil concentration increasing as the animal ages.4,19 In rodents, automated analyzers often incorrectly identify a variable proportion of neutrophils and/or lymphocytes as monocytes.

(Modified Wright’s-Giemsa stain, 1000×.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree