Chapter 2 THE HEAD

The head of the dog is often involved in trauma either from accidents or fighting. The position of the subcutaneous vessels is therefore important in these cases. Surgical repair of skin wounds is a common occurrence and damage to eyes, ears and mouth including the tongue is not uncommon. The tongue may also be involved in burns or electrocution. Teeth are also easily damaged by trauma, excessive chewing or foreign bodies. These foreign bodies may be trapped in the tongue, cheeks, soft palate or teeth. It is worth remembering that the oral and nasal orifices provide easy access for pathogens or excess antigens.

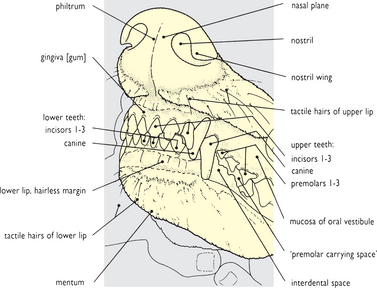

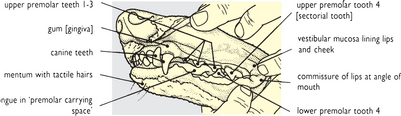

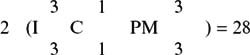

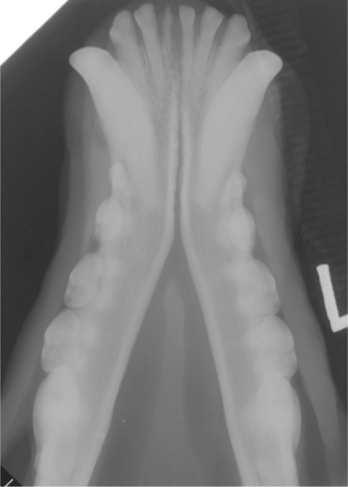

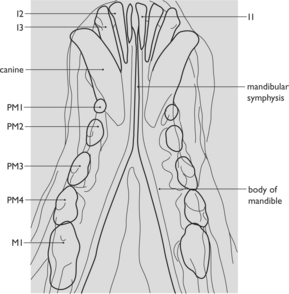

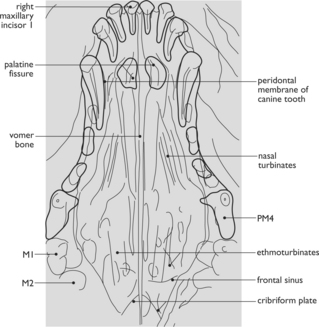

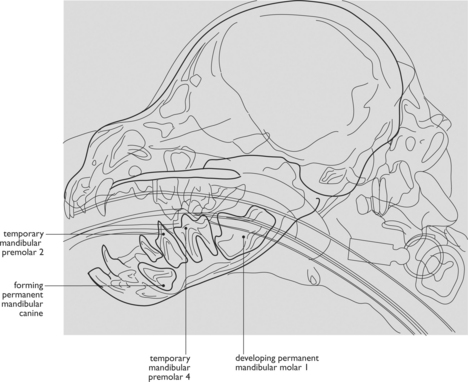

Teeth can be vital in helping to estimate the age of dogs, as the pulp cavities narrow with increasing age. It can be more usual to rely upon the degree of tartar formation wear and general health of the gingiva. Teeth are obviously closely associated with mandible and maxillae. A malar abscess may occur around the root of the 4th (carnassial) upper premolar. It may cause swelling of the face below the eye and will eventually fistulate to the skin. It requires removal to allow drainage. It may be necessary to remove persistent temporary teeth usually the canines. Adult canine teeth have a wide root, greater than the alveolus, and require elevators or removal of lateral wall of alveolus to be able to remove a tooth. The upper and lower canine teeth have extensive roots which reach caudally beneath the roots of the first two pre-molars. The upper carnassial has three roots, is more difficult to remove and is easily damaged by chewing bones etc. It can easily become affected by a root granuloma or a fistula. Prosthetic dentistry is also carried out in show dogs or police dogs. The tonsil may become infected. It is usually obscured by the overlying mucosa of the crypt, but if infected, bulges from the crypt.

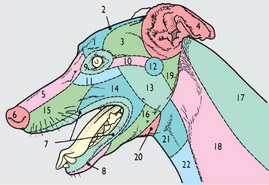

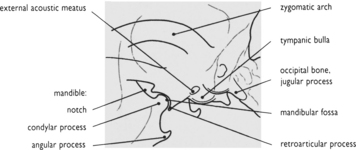

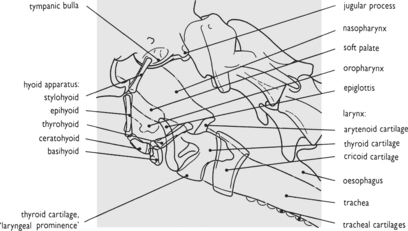

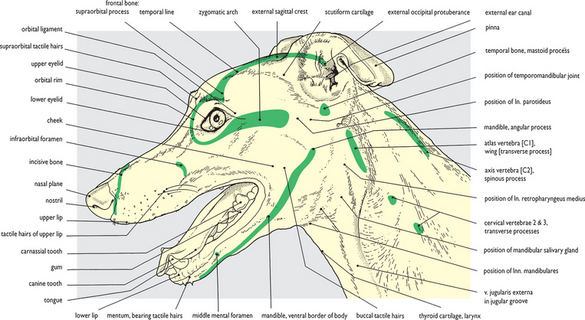

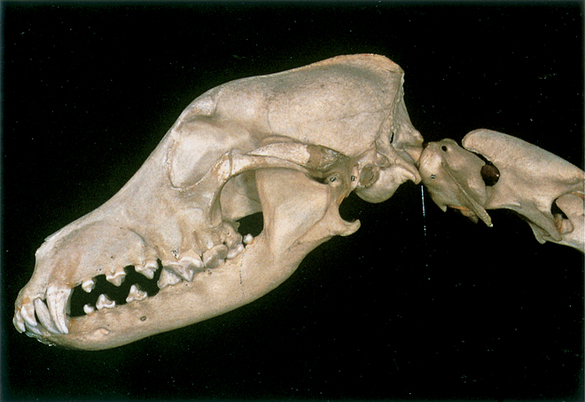

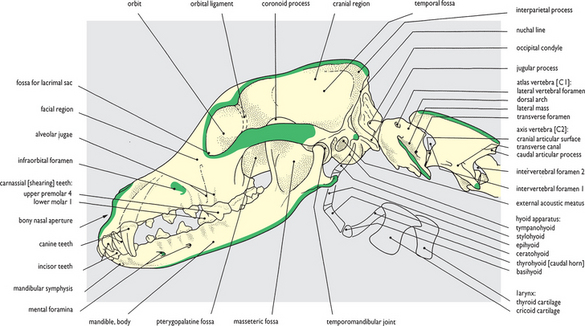

Fig. 2.1 Surface features of the head: left lateral view. The major bony features that are readily palpable and/or visible on the surface of the head are indicated in this figure. These ‘points’ correspond to those colored green on the bones illustrated in Fig. 2.2. Additional palpable features include the thyroid cartilage, the orbital ligament, the temporal and masseter muscles, and the mandibular lymph nodes. The position of the temporomandibular joint rostral to the base of the auricular cartilage is also readily palpable when the mouth is opened and closed carefully. Figs 2.55, 2.59 and 2.125 show the surface of the head from dorsal and ventral views and should be compared with this figure.

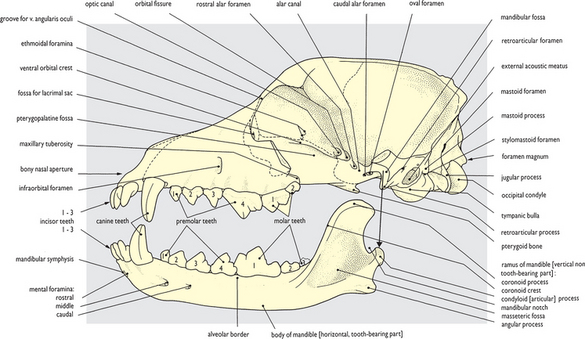

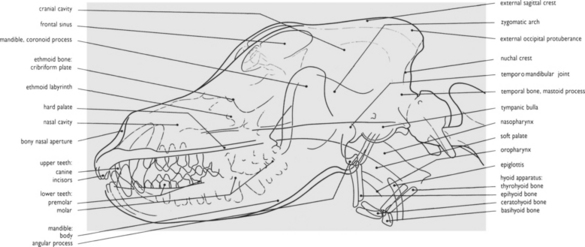

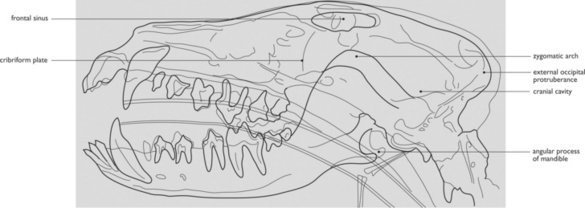

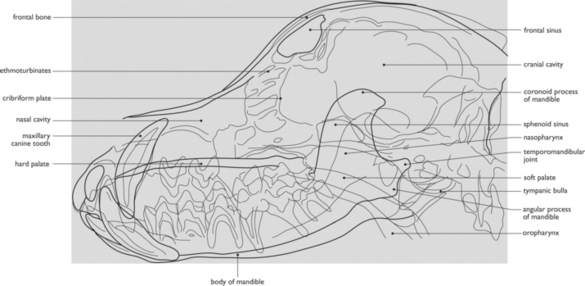

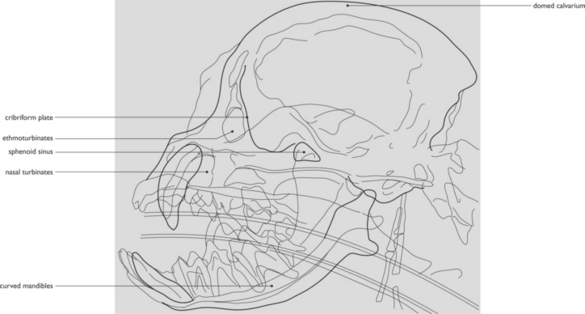

Fig. 2.2 Skeleton of the head: left lateral view. The palpable bony features shown in Fig. 2.1 are colored green on this skull and first three cervical vertebrae. Absent from this skeletal preparation are the hyoid apparatus (the component parts and topographical position are shown in dissections of the pharyngeal region – from lateral view in Figs 2.78–2.83; from medial view in Figs 2.93 and 2.94; and from ventral view in Figs 2.129–2.133), the nasal cartilages (shown in Figs 2.99–2.106), and the auricular cartilages (shown in Figs 2.32 and 2.33, and Figs 2.61–2.67). In addition to distinct palpable ‘points’, large areas of bone can also be felt through the overlying musculature, particularly in the facial region.

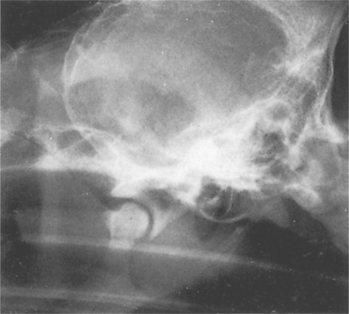

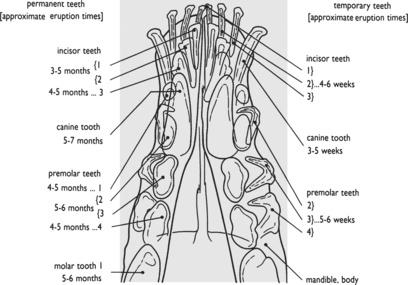

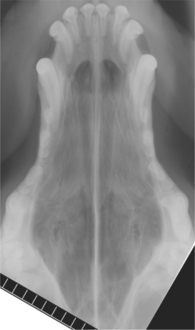

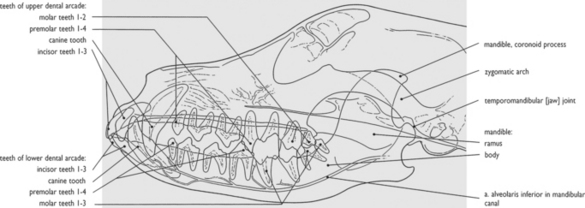

Fig. 2.6 Radiograph of the head: ventrodorsal view. Only the major features are pointed out here, as in fig 2.4. Of particular note is the transverse orientation of the temporomandibular joints and the somewhat narrower lower jaw and lower dental arcade. With jaw action being hinge-like the teeth of the lower dental arcade, especially the first lower molar tooth, show a shearing bite against the lingual surfaces of the teeth of the upper arcade.

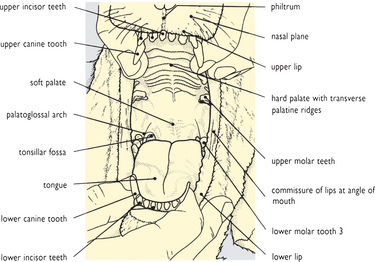

Fig. 2.8 Surface features of the head with mouth open: rostral view. When the mouth is closed the tongue practically fills the oral cavity (see also Fig. 2.143 of the head in transverse section): an open mouth displays mucous membrane covering the tongue and palate and lining the inside of the cheeks. The length of the soft palate should be noted (see also Fig. 2.87) since in brachycephalic breeds it may interfere with air flow through the larynx.

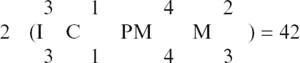

Fig. 2.11 Radiograph of the jaws and permanent teeth: lateral view. Superimposition of upper and lower jaws in a lateral view creates a confusing image of the dental arcades (see fig. 2.4). For this reason a sagittally sectioned head has been radiographed and the permanent dentition on only one side of each jaw is shown. The sectorial (carnassial) teeth – upper fourth premolar and lower first molar – have been labelled in the drawing. The permanent dental formula is:

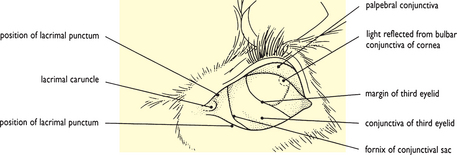

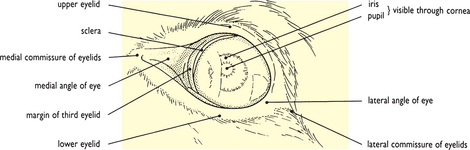

Fig. 2.17 Surface features of the eye: left lateral view (1). The eye is shown with eyelids open. The palpable bony orbital margin is completed laterally by an orbital ligament linking the supraorbital process with the zygomatic arch (cf. Fig. 2.39). A dog has quite a wide field of view, in the order of 240°, and there is some measure of overlap between the fields of left and right eyes when it is looking straight ahead.

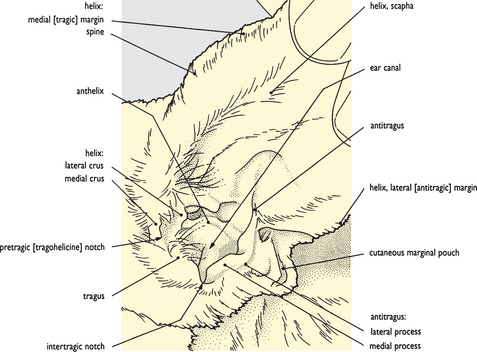

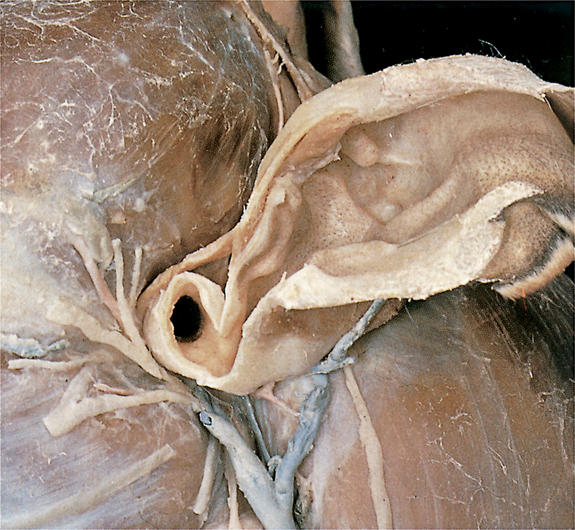

Fig. 2.19 Surface features of the ear: left lateral view. The helix of the pinna has been raised and held erect. From the opening visible in the picture the ear canal extends downwards almost vertically and then turns inwards and forwards at 90° towards the eardrum (see also Fig. 2.145 of the head in transverse section). Consequently lateral traction on the pinna will straighten the canal.

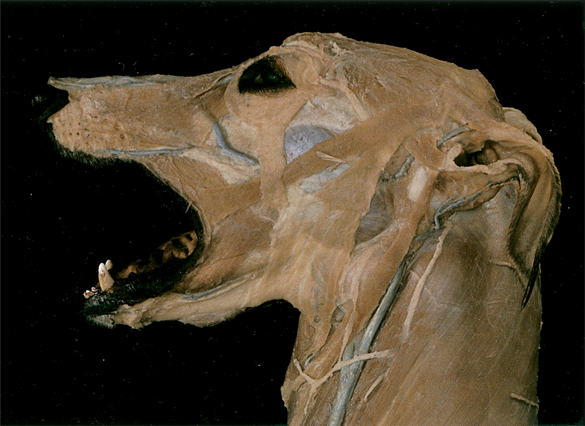

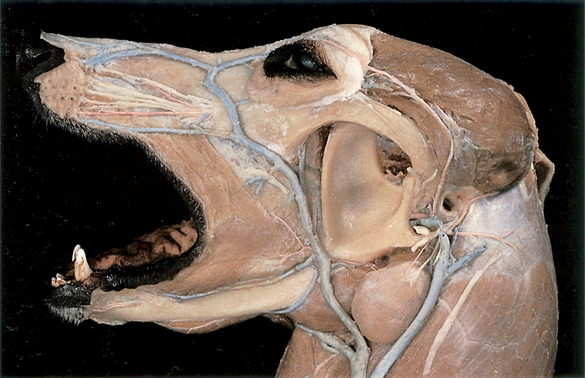

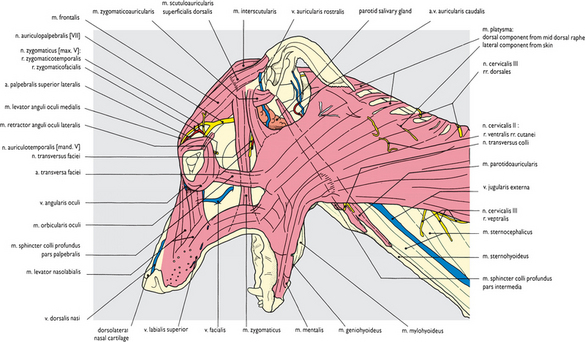

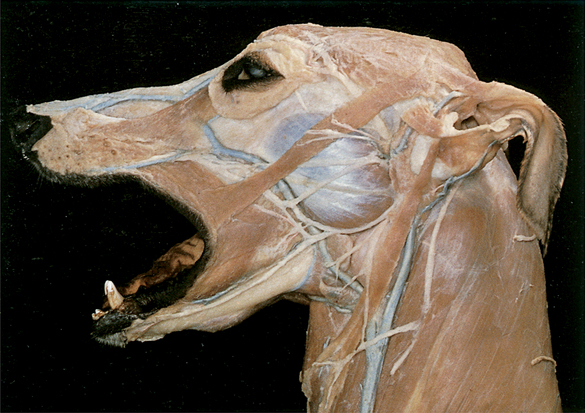

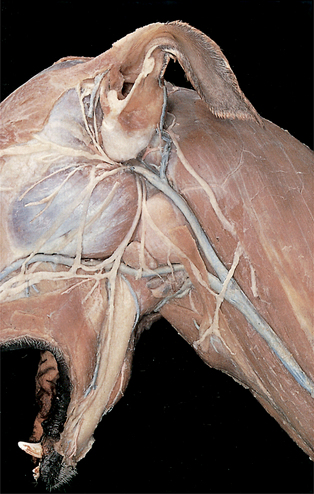

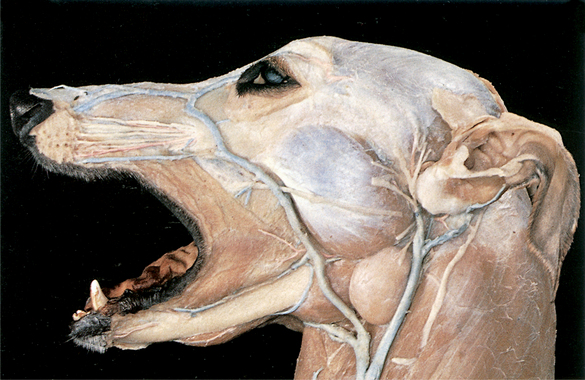

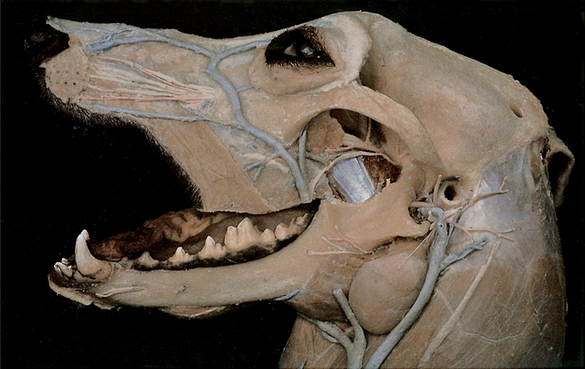

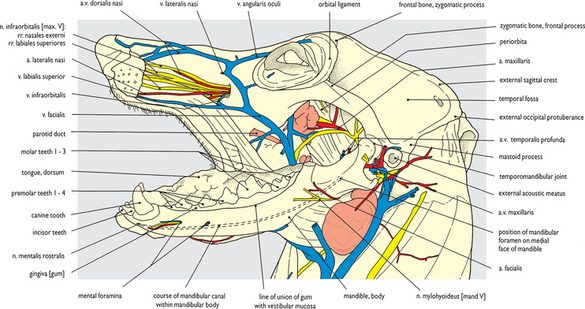

Fig. 2.24 Superficial structures of the head and cranial end of the neck: left lateral view. The skin has been removed apart from a narrow rim in the lips, around the nostril and eye, and on the distal part of the scapha of the auricular cartilage. Because the animal was embalmed with jaws open and head bent down slightly on the neck, the fat and fascia on the underside of the ‘throat’ was preserved as a compressed and ‘waterlogged’ mass. In the process of removing this mass the few delicate transverse strands of the sphincter colli superficialis muscle were removed (see Fig. 3.6). The superficial structures of the head are also shown from dorsal view in Figs 2.57 and 2.61, and from ventral view in Fig. 2.125.

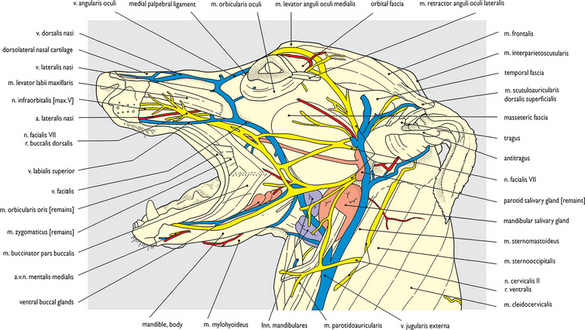

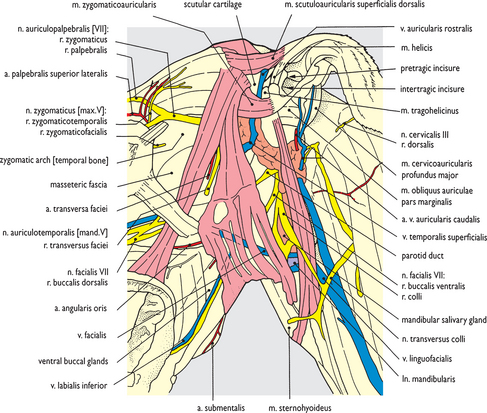

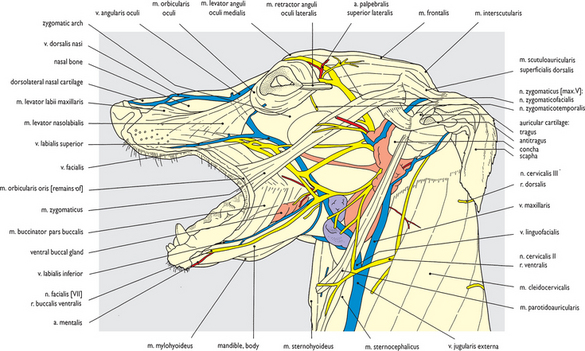

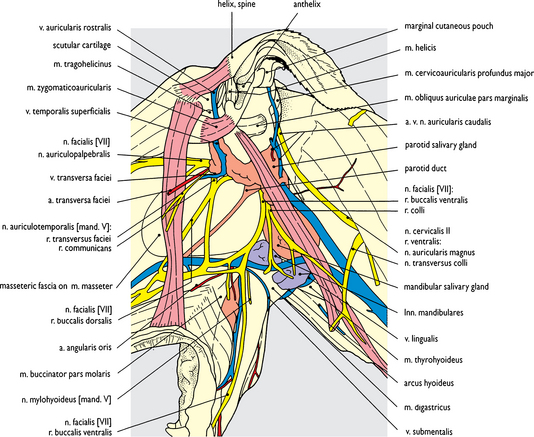

Fig. 2.26 Superficial structures of the temporal, auricular, parotid and masseteric regions after removal of the platysma muscle: left lateral view. This is a closer view of part of the dissection shown in Fig. 2.25. Some limited cleaning of superficial fascia from around the concha of the auricular cartilage exposes the parotid salivary gland and the proximal part of its duct. Cutaneous innervation of the head is through the trigeminal nerve (V), some of the branches being displayed in this dissection (see also Fig. 2.58). However, many of its terminal ramifications have been unavoidably removed along with the skin and platysma muscle so that at best only the proximal stumps of such nerves are preserved intact.

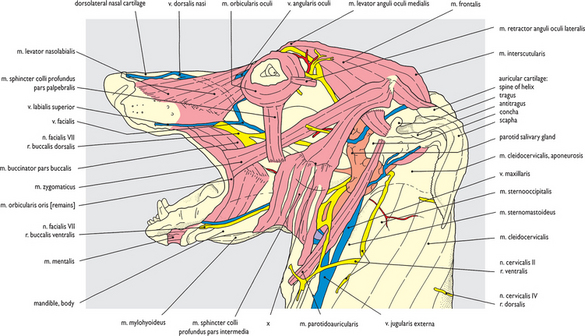

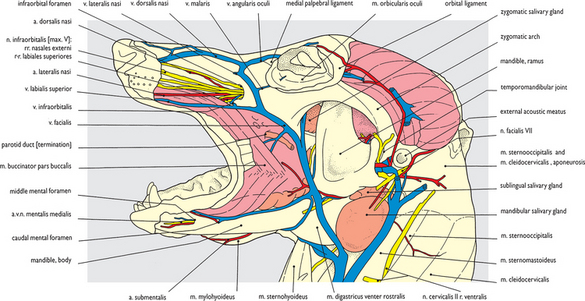

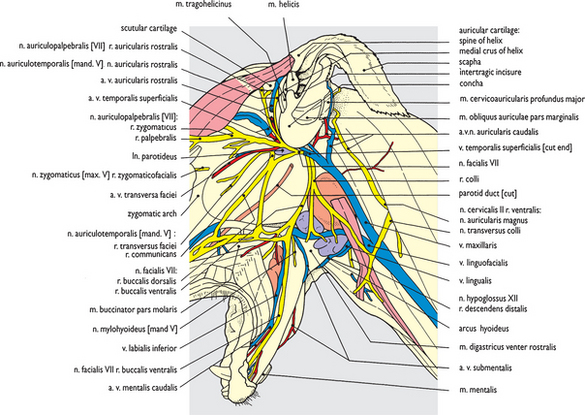

Fig. 2.27 Superficial structures of the head after removal of the platysma and sphincter colli profundus muscles: left lateral view. The intermediate component of the sphincter colli profundus and the nasofrontal part of the levator nasolabialis muscle have been removed. The extensive distribution of the facial nerve (VII) to the facial musculature is contrasted with a less apparent distribution of sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve (V). The ramifications of cutaneous nerves are generally removed with the skin. The extensive and pronounced venous drainage in the superficial fascia is in marked contrast to the more restricted distribution of arteries (see also Fig. 2.127).

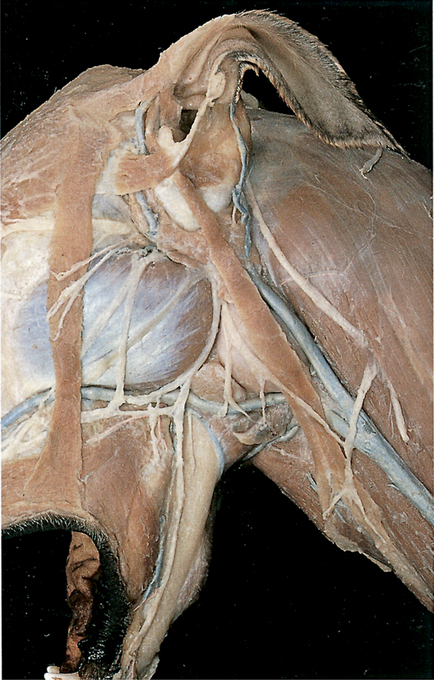

Fig. 2.28 Superficial structures of the temporal, auricular, parotid and masseteric regions after removal of the platysma and sphincter colli profundus muscles: left lateral view. This is a closer view of a part of the dissection shown in Fig. 2.27. Removal of the intermediate part of the sphincter colli profundus has exposed the mandibular lymph nodes (see also Fig. 2.127). These nodes are of considerable size when compared to the very small parotid lymph node exposed in Fig. 2.30. Lymph nodes are generally few in number and small in size (relative to body size) in the dog and lymphatic tissue is generally poorly displayed. Lymphatic vessels (apart from the thoracic duct – see Chapter 5) are not demonstrated.

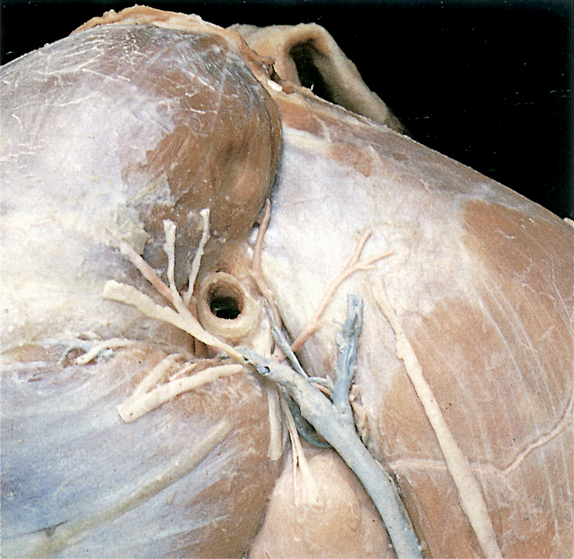

Fig. 2.30 Superficial nerves and blood vessels of the temporal, auricular, parotid and masseteric regions after removal of the facial muscles and parotid salivary glands: left lateral view. This is a closer view of a part of the dissection shown in Fig. 2.29 but with the parotid salivary gland removed, including the proximal part of its duct, and that component of the superficial temporal vein which lay embedded in parotid gland tissue also removed. The cut ends of the vein are visible as it leaves the temporal fascia dorsal to the zygomatic arch, and just before it enters the maxillary vein caudoventral to the concha of the auricular cartilage. The small parotid lymph node, now uncovered, partially obscures the communicating ramus linking the auriculotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve (V) with the dorsal buccal branch of the facial nerve (VII).

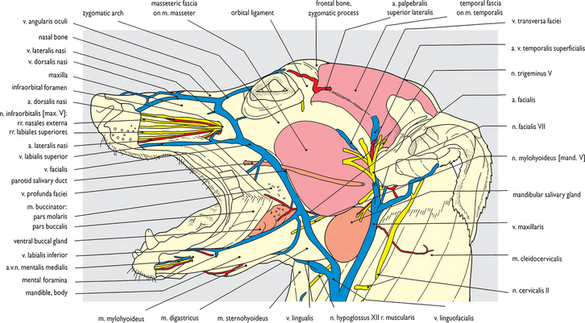

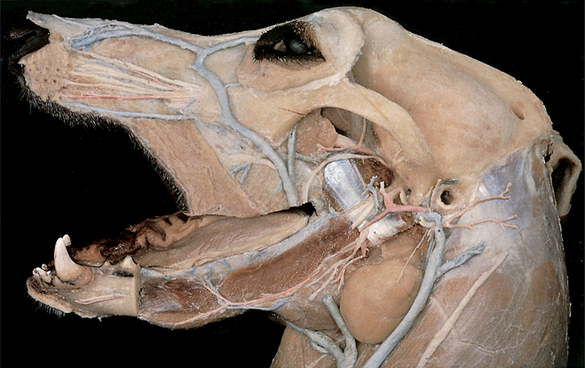

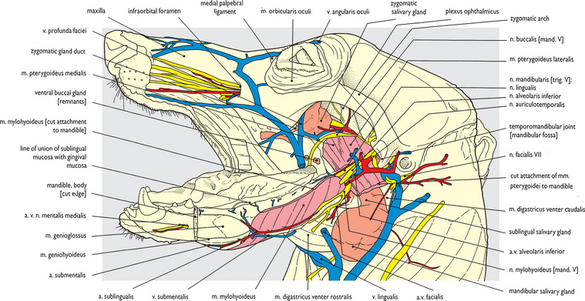

Fig. 2.31 Auricular cartilages, temporal and masseter muscles after removal of the facial muscles: left lateral view. The remaining facial muscles have been removed along with the mandibular and parotid lymph nodes and the terminal ramifications of the facial nerve (VII). Infraorbital branches of the maxillary nerve (trigeminal V) are now visible extending rostrally from the infraorbital foramen into the muzzle. Slight displacement of the facial vein away from the rostroventral border of the masseter muscle has exposed the deep facial vein, the facial artery and the mylohyoid nerve extension onto the face (see also Fig. 2.98).

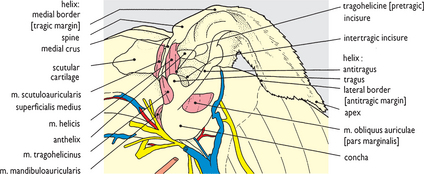

Fig. 2.32 Auricular and scutular cartilages after removal of the superficial muscles and parotid salivary gland: left lateral view. This enlarged view of the auricular region (Fig. 2.31) shows scutular and auricular cartilages and some intrinsic auricular muscles.

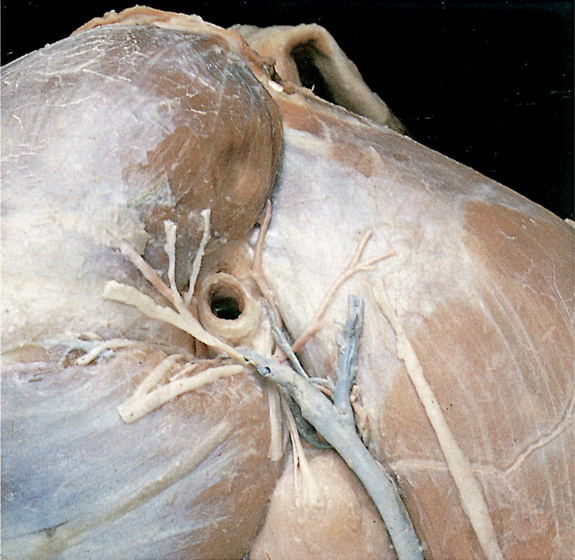

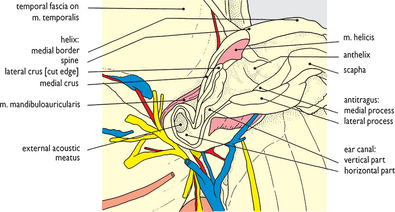

Fig. 2.33 Auricular cartilage and external acoustic canal following tragic resection: left lateral view. The ear canal is opened to demonstrate its right-angled bend before the external acoustic meatus and tympanic membrane are reached (see also sections, Figs 2.145 and 2.146).

Fig. 2.34 Temporal, parotid, auricular and masseteric regions and the external acoustic canal following removal of the auricular cartilage: left lateral view. The facial nerve (VII) emerges from the stylomastoid foramen caudal to the meatus (see Fig. 2.3) and practically encircles it.

Fig. 2.36 Mandibular ramus and temporal muscle after removal of the masseter muscle and temporal fascia: left lateral view (2). This is a closer view of the temporal and masseteric regions of the dissection shown in Fig. 2.35. It displays the deep facial vein leaving the pterygopalatine fossa and embedded to some extent in the zygomatic salivary gland. The buccal nerve from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V) appears in the cheek immediately rostral to the coronoid process of the mandibular ramus. Caudal to the external acoustic meatus the remains of the caudal auricular vessels and nerve have been displaced caudally after removal of the auricular cartilage. They are spread out on the aponeurosis of the cleidocervical and sterno-occipital muscles in the region of the atlas wing.

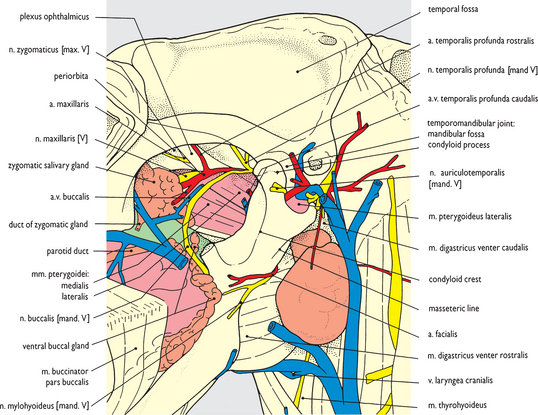

Fig. 2.37 Temporal fossa and mandibular ramus after removal of the temporal and masseter muscles: left lateral view. ‘Piecemeal’ removal of the temporal muscle has left its nerve and blood supply intact and visible through the mandibular notch (see also Figs 2.69 and 2.70). In the process of temporal muscle removal the isolation of orbital structures within the periorbita was clearly apparent: temporal fascia fuses with the orbital ligament whereas the temporal muscle itself merely butts onto but does not attach to the periorbita (see also Fig. 2.70). Likewise, separation of the temporal muscle from the maxillary nerve and blood vessels and buccal nerve in the pterygopalatine fossa ventral to it was readily accomplished (see also Fig. 2.72). The hole in the cranium at the point labelled ‘X’ was made to allow the insertion of a hook to support the head following embalming of the cadaver.

Fig. 2.39 Lower jaw after removal of the masseter muscle, ventral part of the cheek and lower lip: left lateral view. The lower jaw (mandible) has been exposed by removing the lower part of the cheek. From the angle of the mouth a cut was made caudally through the buccinator muscle and buccal fascia to the mandibular ramus at the level at which the coronoid process was removed (see Fig. 2.38). The buccinator muscle was cut from the mandible and the buccal mucosa was severed at its line of reflection from the internal surface of the lip and cheek onto the mandible.

Fig. 2.40 Pterygopalatine fossa and lower jaw after removal of the mandible: left lateral view. The remaining part of the left mandible has been removed by: making a vertical saw cut through the mandibular body caudal to lower premolar tooth 2; disarticulating the temporomandibular joint; severing the digastric, medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid, mylohyoid, geniohyoid and genioglossal muscles at their attachments; cutting the mandibular alveolar vessels and nerve at their entry into the mandibular canal (see Fig. 2.98); severing sublingual mucosa in the floor of the mouth at its line of reflection onto the internal face of the mandible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

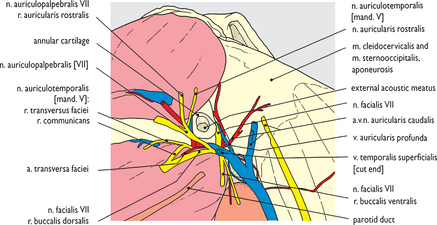

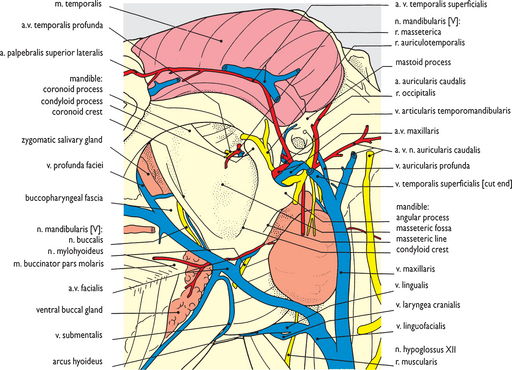

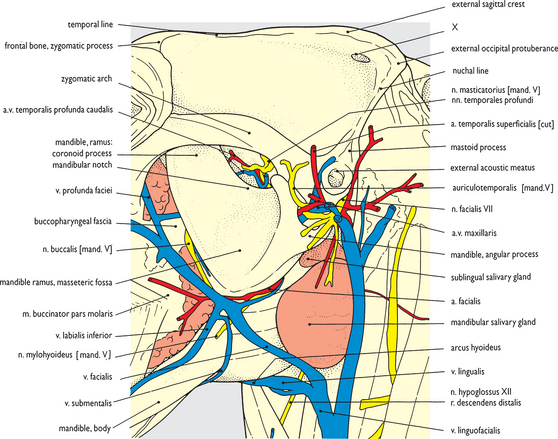

Full access? Get Clinical Tree